Agnosticism

"[6] The English biologist Thomas Henry Huxley said that he originally coined the word agnostic in 1869 "to denote people who, like [himself], confess themselves to be hopelessly ignorant concerning a variety of matters [including the matter of God's existence], about which metaphysicians and theologians, both orthodox and heterodox, dogmatise with the utmost confidence.

[10][11][12] [The agnostic] principle may be stated in various ways, but they all amount to this: that it is wrong for a man to say that he is certain of the objective truth of any proposition unless he can produce evidence which logically justifies that certainty.

[21][22][23] Agnostic (from Ancient Greek ἀ- (a-) 'without' and γνῶσις (gnōsis) 'knowledge') was used by Thomas Henry Huxley in a speech at a meeting of the Metaphysical Society in 1869 to describe his philosophy, which rejects all claims of spiritual or mystical knowledge.

[27] The term agnostic is also cognate with the Sanskrit word ajñasi, which translates literally to "not knowable", and relates to the ancient Indian philosophical school of Ajñana, which proposes that it is impossible to obtain knowledge of metaphysical nature or ascertain the truth value of philosophical propositions; and even if knowledge were possible, it is useless and disadvantageous for final salvation.

[30] Scottish Enlightenment philosopher David Hume contended that meaningful statements about the universe are always qualified by some degree of doubt.

He asserted that the fallibility of human beings means that they cannot obtain absolute certainty except in trivial cases where a statement is true by definition (e.g. tautologies such as "all bachelors are unmarried" or "all triangles have three corners").

[31] Also called "hard", "closed", "strict", or "permanent agnosticism", strong agnosticism is the view that the question of the existence or nonexistence of a deity or deities, and the nature of ultimate reality is unknowable by reason of our natural inability to verify any subjective experience with anything but another subjective experience.

Aristotle,[42] Anselm,[43][44] Aquinas,[45][46] Descartes,[47] and Gödel presented arguments attempting to rationally prove the existence of God.

The skeptical empiricism of David Hume, the antinomies of Immanuel Kant, and the existential philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard convinced many later philosophers to abandon these attempts, regarding it impossible to construct any unassailable proof for the existence or non-existence of God.

For in that case I do not prove anything, least of all an existence, but merely develop the content of a conception.Hume was Huxley's favourite philosopher, calling him "the Prince of Agnostics".

In a letter of September 23, 1860, to Charles Kingsley, Huxley discussed his views extensively:[55][56] I neither affirm nor deny the immortality of man.

I have champed up all that chaff about the ego and the non-ego, noumena and phenomena, and all the rest of it, too often not to know that in attempting even to think of these questions, the human intellect flounders at once out of its depth.And again, to the same correspondent, May 6, 1863:[57] I have never had the least sympathy with the a priori reasons against orthodoxy, and I have by nature and disposition the greatest possible antipathy to all the atheistic and infidel school.

I cannot see one shadow or tittle of evidence that the great unknown underlying the phenomenon of the universe stands to us in the relation of a Father [who] loves us and cares for us as Christianity asserts.

Give me a scintilla of evidence, and I am ready to jump at them.Of the origin of the name agnostic to describe this attitude, Huxley gave the following account:[58] When I reached intellectual maturity and began to ask myself whether I was an atheist, a theist, or a pantheist; a materialist or an idealist; Christian or a freethinker; I found that the more I learned and reflected, the less ready was the answer; until, at last, I came to the conclusion that I had neither art nor part with any of these denominations, except the last.

If one arrives at a negative conclusion concerning the first part of the question, the second part of the question does not arise; and my position, as you may have gathered, is a negative one on this matter.However, later in the same lecture, discussing modern non-anthropomorphic concepts of God, Russell states:[64] That sort of God is, I think, not one that can actually be disproved, as I think the omnipotent and benevolent creator can.In Russell's 1947 pamphlet, Am I An Atheist or an Agnostic?

Russell states:[66] An agnostic thinks it impossible to know the truth in matters such as God and the future life with which Christianity and other religions are concerned.

The Agnostic suspends judgment, saying that there are not sufficient grounds either for affirmation or for denial.Later in the essay, Russell adds:[67] I think that if I heard a voice from the sky predicting all that was going to happen to me during the next twenty-four hours, including events that would have seemed highly improbable, and if all these events then produced to happen, I might perhaps be convinced at least of the existence of some superhuman intelligence.In 1965, Christian theologian Leslie Weatherhead (1893–1976) published The Christian Agnostic, in which he argues:[68] ... many professing agnostics are nearer belief in the true God than are many conventional church-goers who believe in a body that does not exist whom they miscall God.Although radical and unpalatable to conventional theologians, Weatherhead's agnosticism falls far short of Huxley's, and short even of weak agnosticism:[68] Of course, the human soul will always have the power to reject God, for choice is essential to its nature, but I cannot believe that anyone will finally do this.Robert G. Ingersoll (1833–1899), an Illinois lawyer and politician who evolved into a well-known and sought-after orator in 19th-century America, has been referred to as the "Great Agnostic".

[69] In an 1896 lecture titled Why I Am An Agnostic, Ingersoll stated this: [70] Is there a supernatural power—an arbitrary mind—an enthroned God—a supreme will that sways the tides and currents of the world—to which all causes bow?

[74] Historically, a god was any real, perceivable force that ruled the lives of humans and inspired admiration, love, fear, and homage; religion was the practice of it.

Ancient peoples worshiped gods with real counterparts, such as Mammon (money and material things), Nabu (rationality), or Ba'al (violent weather); Bell argued that modern peoples were still paying homage—with their lives and their children's lives—to these old gods of wealth, physical appetites, and self-deification.

In Unfashionable Convictions (1931), he criticized the Enlightenment's complete faith in human sensory perception, augmented by scientific instruments, as a means of accurately grasping Reality.

Firstly, it was fairly new, an innovation of the Western World, which Aristotle invented and Thomas Aquinas revived among the scientific community.

Artistic experience was how one expressed meaning through speaking, writing, painting, gesturing—any sort of communication which shared insight into a human's inner reality.

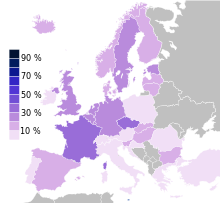

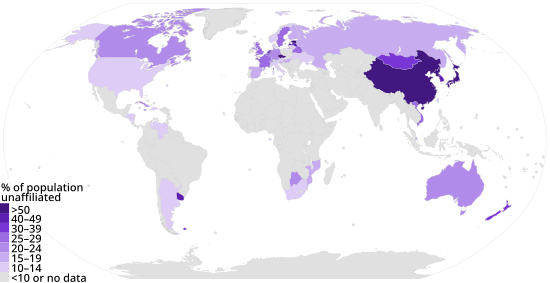

[82] A study conducted by the Pew Research Center found that about 16% of the world's people, the third largest group after Christianity and Islam, have no religious affiliation.

[91][92] According to Pope Benedict XVI, strong agnosticism in particular contradicts itself in affirming the power of reason to know scientific truth.

[93] The Catholic Church sees merit in examining what it calls "partial agnosticism", specifically those systems that "do not aim at constructing a complete philosophy of the unknowable, but at excluding special kinds of truth, notably religious, from the domain of knowledge".

The Council of the Vatican declares, "God, the beginning and end of all, can, by the natural light of human reason, be known with certainty from the works of creation".

[97] According to Richard Dawkins, a distinction between agnosticism and atheism is unwieldy and depends on how close to zero a person is willing to rate the probability of existence for any given god-like entity.

It is a scientific question; one day we may know the answer, and meanwhile we can say something pretty strong about the probability", and considers PAP a "deeply inescapable kind of fence-sitting".

If the chosen definition is not coherent, the ignostic holds the noncognitivist view that the existence of a deity is meaningless or empirically untestable.