Air sac

[2][clarification needed] Theropods, like Aerosteon, have many air sacs in the body that are not just in bones, and they can be identified as the more primitive form of modern bird airways.

[2] Avian pulmonary air sacs are lined with simple epithelial and secretory cells supported by elastin connective tissues.

[20] Changes in air pressure patterns are indicative of respiratory muscle activity and the airflow around the syrinx, the primary vocalization organ of songbirds.

[22] Birdsong primarily occurs in expiration and therefore syllables and fundamental frequency are highly correlated with increased interclavicular air sac pressure.

[24] Since so many aspects of birdsong depend on air sac pressure, there is a trade off between trill rate and the duration of each call, though this has not been studied in depth.

[24] From about 1870 onwards scientists have generally agreed that the post-cranial skeletons of many dinosaurs contained many air-filled cavities (postcranial skeletal pneumaticity)[citation needed], especially in the vertebrae.

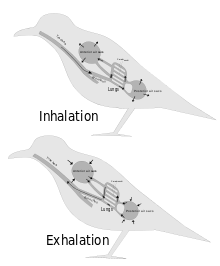

For a long time these cavities were regarded simply as weight-saving devices, but Bakker proposed that they were connected to air sacs like those that make birds' respiratory systems the most efficient of all animals'.

[27] John Ruben et al. (1997, 1999, 2003, 2004) disputed this and suggested that dinosaurs had a "tidal" respiratory system (in and out) powered by a crocodile-like hepatic piston mechanism – muscles attached mainly to the pubis pull the liver backwards, which makes the lungs expand to inhale; when these muscles relax, the lungs return to their previous size and shape, and the animal exhales.

[33] Very few formal rebuttals have been published in scientific journals of Ruben et al.'s claim that dinosaurs could not have had avian-style air sacs; but one points out that the Sinosauropteryx fossil on which they based much of their argument was severely flattened and therefore it was impossible to tell whether the liver was the right shape to act as part of a hepatic piston mechanism.

[34] Some recent papers simply note without further comment that Ruben et al. argued against the presence of air sacs in dinosaurs.

[35] Researchers have presented evidence and arguments for air sacs in sauropods, "prosauropods", coelurosaurs, ceratosaurs, and the theropods Aerosteon and Coelophysis.

If the developmental sequence found in bird embryos is a guide, air sacs actually evolved before the channels in the skeleton that accommodate them in later forms.

Studies indicate that fossils of coelurosaurs,[38] ceratosaurs,[35] and the theropods Coelophysis and Aerosteon exhibit evidence of air sacs.

One study in 2007 concluded that prosauropods likely had abdominal and cervical air sacs, based on the evidence for them in sister taxa (theropods and sauropods).

In addition to providing a very efficient supply of oxygen, the rapid airflow would have been an effective cooling mechanism, which is essential for animals that are active but too large to get rid of all the excess heat through their skins.

[42] The palaeontologist Peter Ward has argued that the evolution of the air sac system, which first appears in the very earliest dinosaurs, may have been in response to the very low (11%) atmospheric oxygen of the Carnian and Norian ages of the Triassic Period.