Air warfare of World War II

But the Luftwaffe was poorly coordinated with overall German strategy, and never ramped up to the size and scope needed in a total war, partly due to a lack of military aircraft production infrastructure for both completed airframes and powerplants when compared to either the Soviet Union or the United States.

When the Luftwaffe's fuel supply ran dry in 1944 due to the oil campaign of World War II, it was reduced to anti-aircraft flak roles, and many of its men were sent to infantry units.

Increasingly heavy losses during the latter part of 1943 due to the reorganized Luftwaffe night fighter system (Wilde Sau tactics), and Sir Arthur Harris' costly attempts to destroy Berlin in the winter of 1943/44, led to serious doubts as to whether Bomber Command was being used to its fullest potential.

However, he repeatedly overruled Arnold by agreeing with Roosevelt's requests in 1941–42 to send half of the new light bombers and fighters to the British and Soviets, thereby delaying the buildup of American air power.

While the Japanese began the war with a superb set of naval aviators, trained at the Misty Lagoon experimental air station, their practice, perhaps from the warrior tradition, was to keep the pilots in action until they died.

Runways, hangars, radar stations, power generators, barracks, gasoline storage tanks, and ordnance dumps had to be built hurriedly on tiny coral islands, mud flats, featureless deserts, dense jungles, or exposed locations still under enemy artillery fire.

Once when heavy rains along the coast reduced the capacity of old airfields, two companies of Airborne Engineers loaded miniaturized gear into 56 transports, flew a thousand miles to a dry Sahara location, started blasting away, and were ready for the first B-17 24 hours later.

This important change of strategy also coincidentally doomed both the twin-engined Zerstörer heavy fighters and their replacement, heavily armed Focke-Wulf Fw 190A Sturmbock forces used as bomber destroyers, each in their turn.

The RAF demonstrated the importance of speed and maneuverability in the Battle of Britain (1940), when its fast Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane fighters easily riddled the clumsy Stukas as they were pulling out of dives.

Bradley was horrified when 77 planes dropped their payloads short of the intended target: The Germans were stunned senseless, with tanks overturned, telephone wires severed, commanders missing, and a third of their combat troops killed or wounded.

The defence line broke; J. Lawton Collins rushed his VII Corps forward; the Germans retreated in a rout; the Battle of France was won; air power seemed invincible.

However, the sight of a senior colleague killed by error was unnerving, and after the completion of operation Cobra, Army generals were so reluctant to risk "friendly fire" casualties that they often passed over excellent attack opportunities that would be possible only with air support.

Lacking a doctrine of strategic bombing, neither the RLM or the Luftwaffe ever ordered any suitable quantities of an appropriate heavy bomber from the German aviation industry, having only the Heinkel He 177A Greif available for such duties, a design plagued with many technical problems, including an unending series of engine fires, with just under 1,200 examples ever being built.

Early in the war, the Luftwaffe had excellent tactical aviation, but when it faced Britain's integrated air defence system, the medium bombers actually designed, produced, and deployed to combat – meant to include the Schnellbomber high-speed mediums, and their intended heavier warload successors, the Bomber B design competition competitors—did not have the numbers or bomb load to do major damage of the sort the RAF and USAAF inflicted on German cities.

The Chinese Air Force however would continue to fight on for years to come as they were replenished through the Sino-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of 1937, and transitioning almost entirely into Soviet-made Polikarpov I-15, I-153 and I-16 fighters as well as Tupolev SB-2 and TB-3 bombers by 1938.

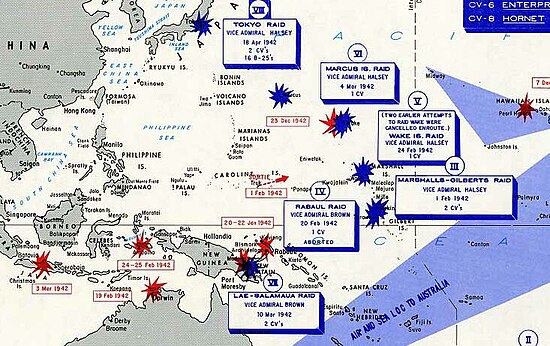

American strategic bombing of Japan from Chinese bases began in 1944, including the firebombing of Wuhan,[62] using Boeing B-29 Superfortress under the command of General Curtis Lemay, but the distances and the logistics made an effective campaign impossible.

The men who had been at jungle airfields longest, the flight surgeons reported, were in the worst shape: The flammability of Japan's large cities, and the concentration of munitions production there, made strategic bombing the preferred strategy of the Americans.

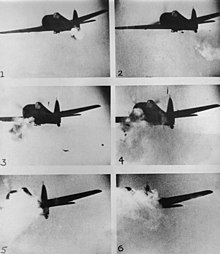

[83] Task Force 58 analyzed the Japanese technique at Okinawa in April, 1945: The Americans decided their best defense against Kamikazes was to knock them out on the ground, or else in the air long before they approached the fleet.

[citation needed] The Kamikaze strategy allowed the use of untrained pilots and obsolete planes, and since evasive maneuvering was dropped and there was no return trip, the scarce gasoline reserves could be stretched further.

[citation needed] Toward the end of the war, the Japanese press encouraged civilians to emulate the kamikaze pilots who willingly gave their lives to stop American naval forces.

[85] Expecting increased resistance, including far more Kamikaze attacks once the main islands of Japan were invaded, the U.S. high command rethought its strategy and used atomic bombs to end the war, hoping it would make a costly invasion unnecessary.

On August 15, Emperor Hirohito announced the surrender of Japan, stating: "Moreover, the enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is indeed incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives.

No fewer than 295 Ju 52s were lost in that venture and in other parts of the country, due to varying circumstances, among which were accurate and effective Dutch anti-aircraft defences and German mistakes in using soggy airfields not able to support the heavy aircraft.

One of Eisenhower's corps commanders, General Lloyd Fredendall, used his planes as a "combat air patrol" that circled endlessly over his front lines ready to defend against Luftwaffe attackers.

Brigade, division, and corps commanders lost control of air assets (except for a few unarmed little "grasshoppers;" observation aircraft that reported the fall of artillery shells so the gunners could correct their aim).

In one "Big Week" in February, 1944, American bombers protected by hundreds of fighters, flew 3,800 sorties dropping 10,000 tons of high explosives on the main German aircraft and ball-bearing factories.

"[117] For the last year of the war German military and civilians retreating towards Berlin were hounded by the presence of Soviet "low flying aircraft" strafing and bombing them, an activity in which even the ancient Polikarpov Po-2, a much produced flight training (uchebnyy) biplane of 1920s design, took part.

To avoid the lethal fast-firing German quadruple 20mm flak guns, pilots came in fast and low (under enemy radar), made a quick run, then disappeared before the gunners could respond.

Airmen protested vigorously against this subordination of the air war to the land campaign, but Eisenhower forced the issue and used the bombers to simultaneously strangle Germany's supply system, burn out its oil refineries, and destroy its warplanes.

[129] One fourth of the German war economy was neutralized because of direct bomb damage, the resulting delays, shortages, and roundabout solutions, and the spending on anti-aircraft, civil defence, repair, and removal of factories to safer locations.