Al-Aqsa Mosque

The mosque was rebuilt by the Fatimid caliph al-Zahir (r. 1021–1036), who reduced it to seven aisles but adorned its interior with an elaborate central archway covered in vegetal mosaics; the current structure preserves the 11th-century outline.

During the periodic renovations undertaken, the ruling Islamic dynasties constructed additions to the mosque and its precincts, such as its dome, façade, minarets, and minbar and interior structure.

More renovations, repairs, and expansion projects were undertaken in later centuries by the Ayyubids, the Mamluks, the Ottomans, the Supreme Muslim Council of British Palestine, and during the Jordanian occupation of the West Bank.

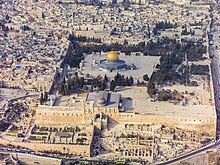

[12][13][14] Arabic and Persian writers such as 10th-century geographer al-Muqaddasi,[15] 11th-century scholar Nasir Khusraw,[15] 12th-century geographer al-Idrisi[16] and 15th-century Islamic scholar Mujir al-Din,[2][17] as well as 19th-century American and British Orientalists Edward Robinson,[12] Guy Le Strange and Edward Henry Palmer explained that the term Masjid al-Aqsa refers to the entire esplanade plaza also known as the Temple Mount or Haram al-Sharif ('Noble Sanctuary') – i.e. the entire area including the Dome of the Rock, the fountains, the gates, and the four minarets – because none of these buildings existed at the time the Quran was written.

[28] The mosque resides on an artificial platform that is supported by arches constructed by Herod's engineers to overcome the difficult topographic conditions resulting from the southward expansion of the enclosure into the Tyropoeon and Kidron valleys.

[34] By comparing the photographs to Hamilton's excavation report, Di Cesare determined that they belong to the second phase of mosque construction in the Umayyad period.

[38] The architectural historian K. A. C. Creswell notes that Arculf's attestation lends credibility to claims by some Islamic traditions and medieval Christian chronicles, which he otherwise deems legendary or unreliable, that the second Rashidun caliph, Umar (r. 634–644), ordered the construction of a primitive mosque on the Temple Mount.

[47] As both were intentionally built on the same axis, Grabar comments that the two structures form "part of an architecturally thought-out ensemble comprising a congregational and a commemorative building", the al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock, respectively.

The last Umayyad caliph, Marwan II (r. 744–750), punished Jerusalem's inhabitants for supporting a rebellion against him by rival princes, and tore down the city's walls.

[59] The Jerusalemite geographer al-Muqaddasi, writing in 985, provided the following description: This mosque is even more beautiful than that of Damascus ... the edifice [after al-Mahdi's reconstruction] rose firmer and more substantial than ever it had been in former times.

[60]Al-Muqaddasi further noted that the mosque consisted of fifteen aisles aligned perpendicularly to the qibla and possessed an elaborately decorated porch with the names of the Abbasid caliphs inscribed on its gates.

[57] According to Hamilton, al-Muqaddasi's description of the Abbasid-era mosque is corroborated by his archaeological findings in 1938–1942, which showed the Abbasid construction retained some parts of the older structure and had a broad central aisle topped by a dome.

[71] It marked the first instance of this Quranic verse being inscribed in Jerusalem, leading Grabar to hypothesize that it was an official move by the Fatimids to magnify the site's sacred character.

[73]Al-Zahir's substantial investment in the Haram, including the al-Aqsa Mosque, amid the political instability in the capital Cairo, rebellions by Bedouin tribes, especially the Jarrahids of Palestine, and plagues, indicate the caliph's "commitment to Jerusalem", in Pruitt's words.

[74] Although the city had experienced decreases in its population in the preceding decades, the Fatimids attempted to build up the magnificence and symbolism of the mosque, and the Haram in general, for their own religious and political reasons.

In order to prepare the mosque for Friday prayers, within a week of his capture of Jerusalem Saladin had the toilets and grain stores installed by the Crusaders at al-Aqsa removed, the floors covered with precious carpets, and its interior scented with rosewater and incense.

They made architectural contributions elsewhere on the Haram, including building the Fountain of Qasim Pasha (1527) and three free-standing domes—the most notable being the Dome of the Prophet built in 1538, and restoring the Pool of Raranj.

[85] The first renovation in the 20th century occurred in 1922, when the Supreme Muslim Council under Amin al-Husayni (the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem) commissioned Turkish architect Ahmet Kemalettin Bey to restore al-Aqsa Mosque and the monuments in its precincts.

The council also commissioned British architects, Egyptian engineering experts and local officials to contribute to and oversee the repairs and additions which were carried out in 1924–25 by Kemalettin.

Other repairs included the partial reconstruction of the jambs and lintels of the central doors, the refacing of the front of five bays of the porch, and the demolition of the vaulted buildings that formerly adjoined the east side of the mosque.

On 21 August 1969, a fire was started by a visitor from Australia named Denis Michael Rohan,[89] an evangelical Christian who hoped that by burning down al-Aqsa Mosque he would hasten the Second Coming of Jesus.

[81][dubious – discuss] The al-Aqsa Mosque has seven aisles of hypostyle naves with several additional small halls to the west and east of the southern section of the building.

The capitals of the columns are of four different kinds: those in the central aisle are heavy and primitively designed, while those under the dome are of the Corinthian order,[96] and made from Italian white marble.

[110] Muslims who are residents of Israel or visiting the country and Palestinians living in East Jerusalem are normally allowed to enter the Temple Mount and pray at al-Aqsa Mosque without restrictions.

[118] According to UNESCO's special envoy to Jerusalem Oleg Grabar, buildings and structures on the Temple Mount are deteriorating due mostly to disputes between the Israeli, Palestinian and Jordanian governments over who is actually responsible for the site.

[119] In February 2007, the department started to excavate a site for archaeological remains in a location where the government wanted to rebuild a collapsed pedestrian bridge leading to the Mughrabi Gate, the only entrance for non-Muslims into the Temple Mount complex.

Jewish settlers broke an agreement between Israel and Jordan and performed prayers and read from the Torah inside the compound, an area normally off limits to non-Muslims.

[124] On 16 April, seventy thousand Muslims prayed in the compound around the mosque, the largest gathering since the beginning of the COVID pandemic; police barred most from entering the structure itself.

[126][127] On 15 April 2022, Israeli forces entered the Temple Mount and used tear gas shells and sound bombs to disperse Palestinians who, they said, were throwing stones at policemen.

He] has renovated it, our lord Ali Abu al-Hasan the imam al-Zahir li-i'zaz Din Allah, Commander of the Faithful, son of al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, Commander of the Faithful, may the blessing of God be on him and his pure ancestors, and on his noble descendants [Shia religious formula alluding to the descendants of Muhammad through his daughter Fatima and her husband Ali, Muhammad's cousin].