Al-Kateb v Godwin

(per McHugh, Hayne, Callinan and Heydon JJ) Al-Kateb v Godwin,[2] was a decision of the High Court of Australia, which ruled on 6 August 2004 that the indefinite detention of a stateless person was lawful.

The case concerned Ahmed Al-Kateb, a Palestinian man born in Kuwait, who moved to Australia in 2000 and applied for a temporary protection visa.

The Commonwealth Minister for Immigration's decision to refuse the application was upheld by the Refugee Review Tribunal and the Federal Court.

The controversy surrounding the outcome of the case resulted in a review of the circumstances of twenty-four stateless people in immigration detention.

Al-Kateb and 8 other stateless people were granted bridging visas in 2005 and while this meant they were released from detention, they were unable to work, study or obtain various government benefits.

[5] In December 2000, Al-Kateb, travelling by boat, arrived in Australia without a visa or passport, and was taken into immigration detention under the provisions of the Migration Act 1958.

[2] However attempts by the Government of Australia to remove Al-Kateb to Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, Syria, and the Palestinian territories (which would have required the approval of Israel) failed.

The appeal was removed into the High Court at the request of the then Attorney-General of Australia Daryl Williams, under provisions of the Judiciary Act 1903.

Section 196 of the Migration Act provides that unlawful non-citizens can only be released from immigration detention if they are granted a visa, deported, or removed from Australia.

[13] Section 198(6) of the Act requires immigration officials to "remove [from Australia] as soon as reasonably practicable an unlawful non-citizen".

Detention generally is considered to be a judicial function, which can be exercised only by courts, pursuant to Chapter III of the Australian Constitution.

In this situation, the court had decided in previous cases that immigration detention, for the purposes of processing and removal, did not infringe on Chapter III.

Al-Kateb argued that if indeed the provisions of the Migration Act extended as far as to allow the indefinite detention of people like him, then it would have gone beyond those valid purposes and would infringe Chapter III.

The respondents focused on the case in which this system of exceptions was first articulated, Chu Kheng Lim v Minister for Immigration, Local Government and Ethnic Affairs.

[17] The respondents also noted that Gaudron made similar comments in the Stolen Generations case,[18] which also considered non-judicial detention in the context of Aboriginal children who were forcibly removed from their parents' care.

[2] Justice McHugh stated simply that the language of the sections was not ambiguous, and clearly required the indefinite detention of Al-Kateb.

Justice Hayne concluded that the detention scheme in the Migration Act did not contravene Chapter III because, fundamentally, it was not punitive.

While conceding that the scope of the Parliament's powers with respect to defence will be greater in wartime than in peacetime, Kirby said that they could not extend so far as to displace fundamental constitutional requirements such as those in Chapter III.

[22] Arthur Glass observed that the minority judges began their judgments from the position that indefinite non-judicial detention and the curtailment of personal freedom were troubling consequences, and he noted that "as is not uncommon in statutory construction, where you start from is critical to where you end up".

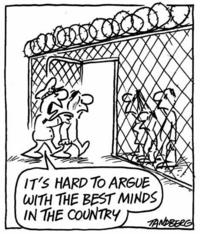

[23] Marr accused the majority of deciding that "saving Australia from boat people counts for more than Al-Kateb's raw liberty".

[19] However, the conditions of the bridging visas did not permit holders to work, study, obtain social security benefits or receive healthcare from Medicare, and Al-Kateb remained entirely dependent on donations from friends and supporters to survive.

[24] In response to McHugh's speech, Chief Justice Gleeson said that the issue of whether or not Australia should have a bill of rights was a purely political one and not a matter for the courts.

Christopher Richter suggested that the majority's legalistic approach, while yielding a workable construction of the provisions of the Migration Act, resulted in a dangerous situation in this case because the Act did not specifically address the situation of stateless persons, and the literal approach did not allow for gaps in the legislation to be filled.

He argues that the majority, particularly Justice Callinan, preferred the plain meaning of the Migration Act because for them, "the key principle at play is simple: the Court should not frustrate Parliament's purpose or obstruct the executive".

[26] Zagor also comments on the irony that the supposedly-legalistic conclusion reached by the majority is at odds with a prior High Court decision, led by Australia's most prominent legalist, Chief Justice Owen Dixon, who implied a temporal limit onto World War II-era legislation, which also included a scheme of executive detention.

[12] Several commentators have expressed the view that the decision has produced confusion and uncertainty with respect to constitutional restrictions on executive power in this area.

Finally, Zagor argues that of the Justices who questioned the Chu Kheng Lim test, none were able to provide a coherent alternative to substitute for it.