Alaska Mental Health Enabling Act

It became the focus of a major political controversy[1] after opponents nicknamed it the "Siberia Bill" and denounced it as being part of a communist plot to hospitalize and brainwash Americans.

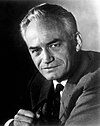

The legislation in its original form was sponsored by the Democratic Party, but after it ran into opposition, it was rescued by the conservative Republican Senator Barry Goldwater.

Under Goldwater's sponsorship, a version of the legislation without the commitment provisions that were the target of intense opposition from a variety of far-right, anti-Communist and fringe religious groups was passed by the United States Senate.

The asset stripping was eventually ruled to be illegal following several years of litigation, and a reconstituted mental health trust was established in the mid-1980s.

On June 6, 1900, the United States Congress enacted a law permitting the government of the then District of Alaska to provide mental health care for Alaskans.

They highlighted the deficiencies of the program: commitment procedures in Alaska were archaic, and the long trip to Portland had a negative effect on patients and their families.

At the start of 1956, in the second session of the 84th Congress, Representative Edith Green (D-Oregon) introduced the Alaska Mental Health Bill (H.R.

The trust would then be able to use the assets of the transferred land (principally mineral and forestry rights) to obtain an ongoing revenue stream to fund the Alaskan mental health program.

It then fell to the Senate to consider the equivalent bill in the upper chamber, S. 2518, which was expected to have an equally untroubled passage following hearings scheduled to begin on February 20.

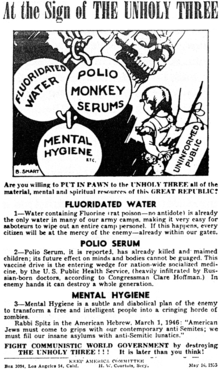

[4] In December 1955, a small anti-communist women's group in Southern California, the American Public Relations Forum (APRF), issued an urgent call to arms in its monthly bulletin.

[6] The APRF's membership overlapped with that of the much larger Minute Women of the U.S.A., a nationwide organization of militant anti-communist housewives[citation needed][who?]

The answer, based on a study of the bill, indicates that it is entirely within the realm of possibility that we may be establishing in Alaska our own version of the Siberia slave camps run by the Russian government.

[7]After the Santa Ana Register published its article, a nationwide network of activists began a vociferous campaign to torpedo the Alaska Mental Health Bill.

In his February 17 bulletin, Dan Smoot told his subscribers: "I do not doubt that the Alaska Mental Health Act was written by sincere, well-intentioned men.

The Keep America Committee of Los Angeles similarly called the proponents of the bill a "conspiratorial gang" that ought to be "investigated, impeached, or at least removed from office" for treason.

[2] Retired brigadier general Herbert C. Holdridge sent a public letter to President Dwight Eisenhower on March 12, in which he called the bill "a dastardly attempt to establish a concentration camp in the Alaskan wastes".

There was some initial opposition from the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons, a small and extremely conservative body which opposed socialized medicine; Dr. L. S. Sprague of Tucson, Arizona said in its March 1956 newsletter that the bill widened the definition of mental health to cover "everything from falling hair to ingrown toenails".

[3] By March 1956, it was being said in Washington, D.C. that the amount of correspondence on the bill exceeded anything seen since the previous high-water mark of public controversy, the Lend-Lease Act of 1941.

[2] Numerous letter-writers protested to their Congressional representatives that the bill was "anti-religious" or that the land to be transferred to the Alaska Mental Health Trust would be fenced off and used as a concentration camp for the political enemies of various state governors.

"[10] A letter printed in the Daily Oklahoman newspaper in May 1956 summed up many of the arguments made by opponents of the bill: The advocates of world government, who regard patriotism as the symptom of a diseased mind, took a step closer to their goal of compulsory asylum 'cure' for opponents of UNESCO, when, on January 18, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Alaska Mental Health Act.

It closely follows the Model Code, drafted by the American Psychiatric association, which has been working with the World Health Organization, a specialized agency of the United Nations ...

We deplore the present antiquated methods of handling our mentally ill." It also urged the National Council of Churches to mobilize support for the bill.

In 1978, the Alaska Legislature passed a law to abolish the trust and transfer the most valuable parcels of lands to private individuals and the government.

The case of Weiss v State of Alaska eventually became a class action lawsuit involving a range of mental health care groups.

[16] The Alaska Mental Health Bill plays a major part in the Church of Scientology's account of its campaign against psychiatry.

Scientology may also have provided an important piece of the "evidence" which the anti-bill campaigners used — a booklet titled Brain-Washing: A Synthesis of the Russian Textbook on Psychopolitics.

In a public address in 1995, he told Scientologists that it was "in 1955 that the agents for the American Psychiatric Association met on Capitol Hill to ram home the infamous Siberia Bill, calling for a secret concentration camp in the wastes of Alaska."

It was "here that Mr. Hubbard, as the leader of a new and dynamic religious movement, knocked that Siberia Bill right out of the ring — inflicting a blow they would never forget.