Albanian paganism

[7] Indeed, the Kanun contains several customary concepts that clearly have their origins in pagan beliefs, including in particular the ancestor worship, animism and totemism, which have been preserved since pre-Christian times.

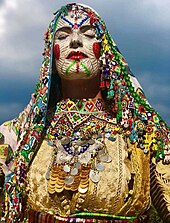

[8][9][10] Albanian traditions have been orally transmitted – through memory systems that have survived intact into modern times – down the generations and are still very much alive in the mountainous regions of Albania, Kosovo and western North Macedonia, as well as among the Arbëreshë in Italy and the Arvanites in Greece, and the Arbanasi in Croatia.

[19] The Moon is worshiped as a goddess, with her cyclical phases regulating many aspects of Albanian life, defining agricultural and livestock activities, various crafts, and human body.

The Fire – Zjarri, evidently also called with the theonym Enji – is deified in Albanian tradition as releaser of light and heat with the power to ward off darkness and evil, affect cosmic phenomena and give strength to the Sun, and as sustainer of the continuity between life and afterlife and between the generations, ensuring the survival of the lineage (fis or farë).

[24] Besa is a common practice in Albanian culture, consisting of an oath (be) solemnly taken by sun, by moon, by sky, by earth, by fire, by stone and thunderstone, by mountain, by water, and by snake, which are all considered sacred objects.

[31] Albanian beliefs, myths and legends are organized around the dualistic struggle between good and evil, light and darkness,[32] the most famous representation of which is the constant battle between drangue and kulshedra,[33] a conflict that symbolises the cyclic return in the watery and chthonian world of death, accomplishing the cosmic renewal of rebirth.

[66] Early evidence of the celestial cult in Illyria is provided by 6th century BCE plaques from Lake Shkodra, which belonged to the Illyrian tribal area of what was referred in historical sources to as the Labeatae in later times.

These relations can be seen during the rule of the Illyrian emperors, such as Aurelian who introduced the cult of the Sun; Diocletian who stabilized the empire and ensured its continuation through the institution of the Tetrarchy; Constantine the Great who issued the Edict of Toleration for the Christianized population and who summoned the First Council of Nicaea involving many clercs from Illyricum; Justinian who issued the Corpus Juris Civilis and sought to create an Illyrian Church, building Justiniana Prima and Justiniana Secunda, which was intended to become the centre of Byzantine administration.

Also according to Church documents, the territories that coincide with the present-day Albanian-speaking compact area had remained under the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Rome and used Latin as official language at least until the first half of the 8th century.

[16] British poet Lord Byron (1788–1824), describing the Albanian religious belief, reported that "The Greeks hardly regard them as Christians, or the Turks as Muslims; and in fact they are a mixture of both, and sometimes neither.

[6] Albanian traditions have been orally transmitted – through memory systems that have survived intact into modern times – down the generations and are still very much alive in the mountainous regions of Albania, Kosovo and western North Macedonia, as well as among the Arbëreshë in Italy and the Arvanites in Greece, and the Arbanasi in Croatia.

[97][98] The Fire – Zjarri – is deified as releaser of light and heat with the power to ward off darkness and evil, affect cosmic phenomena and give strength to the Sun, and as sustainer of the continuity between life and afterlife and between the generations.

[22] The primeval religiosity of the Albanian mountains is expressed by a supreme deity who is the god of the universe and who is conceived through the belief in the fantastic and supernatural entities, resulting in an extremely structured imaginative creation.

[99][100] The components of Nature are animated and personified deities, so in Albanian folk beliefs and mythology the Sky (Qielli) with the clouds and lightning, the Sun (Dielli), the Moon (Hëna), and the stars (including Afërdita), the Fire (Zjarri) and the hearth (vatra), the Earth (Dheu/Toka) with the mountains, stones, caves, and water springs, etc., are cult objects, considered to be participants in the world of humans influencing the events in their life, and afterlife as well.

[108] Ritual calendar fires (Zjarret e Vitit) are practiced in relation to the cosmic cycle and the rhythms of agricultural and pastoral life, with the function to give strength to the Sun and to ward off evil according to the old beliefs.

[24] Exercising a great influence on Albanian major traditional feasts and calendar rites, the Sun (Dielli) is worshiped as the god of light and giver of life, who fades away the darkness of the world and melts the frost, allowing the renewal of Nature.

[109] The most famous Albanian mythological representation of the dualistic struggle between good and evil, light and darkness, is the constant battle between drangue and kulshedra,[33] a conflict that symbolises the cyclic return in the watery and chthonian world of death, accomplishing the cosmic renewal of rebirth.

[68] Finding correspondences with Albanian folk beliefs and practices, early evidence of the celestial cult in Illyria is provided by 6th century BCE Illyrian plaques from Lake Shkodra, depicting simultaneously sacred representations of the sky and the sun, and symbolism of lightning and fire, as well as the sacred tree and birds (eagles); the Sun deity is animated with a face and two wings, throwing lightning into a fire altar.

[27] Albanian rituals to avert big storms with torrential rains, lightning, and hail, seek assistance from the supernatural power of the Fire (Zjarri, evidently also called with the theonym Enji).

[124] The cult practiced by the Albanians on several sacred mountains (notably on Mount Tomorr in central Albania) performed with pilgrimages, prayers to the Sun, ritual bonfires, and animal sacrifices,[125] is considered a continuation of the ancient Indo-European sky-god worship.

Regarded as an earth-deity, the serpent is euphemistically called with names that are derived form the Albanian words for earth, dhé and tokë: Dhetokësi, Dheu, Përdhesi, Tokësi or Itokësi.

Albanian major traditional festivities and calendar rites are based on the Sun, worshiped as the god of light, sky and weather, giver of life, health and energy, and all-seeing eye.

[182] The Fire – Zjarri – is deified in Albanian tradition as releaser of light and heat with the power to ward off darkness and evil, affect cosmic phenomena and give strength to the Sun, and as sustainer of the continuity between life and afterlife and between the generations.

Zjarri i Vatrës ("the Fire of the Hearth") is regarded as the offspring of the Sun and the sustainer of the continuity between the world of the living and that of the dead and between the generations, ensuring the survival of the lineage (fis or farë).

[24] The ritual collective fires (based on the house, kinship, or neighborhood) or bonfires in yards (especially on high places) lit before sunrise to celebrate the main traditional Albanian festivities such as Dita e Verës (spring equinox), Shëngjergji, Shën Gjini–Shën Gjoni (summer solstice), the winter festivals (winter solstice), or mountain pilgrimages, often accompanied by animal sacrifices, are related to the cult of the Sun, and in particular they are practiced with the function to give strength to the Sun and to ward off evil according to the old beliefs.

Some of the main heroes of the Albanian epic songs, legends and myths are: E Bija e Hënës dhe e Diellit "the Daughter of the Moon and the Sun" is described as pika e qiellit, "the drop of the sky or lightning", which falls everywhere from heaven on the mountains and the valleys and strikes pride and evil.

Drangue is a semi-human winged warrior who fights the kulshedra; his most powerful weapons are lightning-swords and thunderbolts, but he also uses meteoric stones, piles of trees and rocks; In Albanian paganism, there is a unique tradition about children born with the essence of dragons.

Albanologist Johann Georg von Hahn (1811 – 1869) reported that clergy, during his time and before, have vigorously fought the pagan rites that were practiced by Albanians to celebrate this festivity, but without success.

[311] The old rites of this festivity were accompanied by collective fires based on the house, kinship or neighborhood, a practice performed in order to give strength to the Sun according to the old beliefs.

[312] The richest set of rites related to buzmi are found in northern Albania (Mirdita, Pukë, Dukagjin, Malësia e Madhe, Shkodër and Lezhë), as well as in Kosovo, Dibër and so on.