Albert Ball

At the time of his death he was the United Kingdom's leading flying ace, with 44 victories, and remained its fourth-highest scorer behind Edward Mannock, James McCudden, and George McElroy.

He died when his plane crashed into a field in France on 7 May, sparking a wave of national mourning and posthumous recognition, which included the award of the Victoria Cross for his actions during his final tour of duty.

His parents were Albert Ball, a successful businessman who rose from employment as a plumber to become Lord Mayor of Nottingham, and who was later knighted, and Harriett Mary Page.

[5] This did not curb his daring in such boyhood pursuits as steeplejacking;[6] on his 16th birthday, he accompanied a local workman to the top of a tall factory chimney and strolled about unconcerned by the height.

[2][8] Following the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, Ball enlisted in the British Army, joining the 2/7th (Robin Hood) Battalion of the Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment).

In an attempt to see action, he transferred early the following year to the North Midlands Cyclist Company, Divisional Mounted Troops, but remained confined to a posting in England.

[12] In June, he decided to take private flying lessons at Hendon Aerodrome, which would give him an outlet for his interest in engineering and possibly help him to see action in France sooner.

[15] In letters home Ball recorded that he found flying "great sport", and displayed what Peter de la Billière described as "almost brutal" detachment regarding accidents suffered by his fellow trainees: Yesterday a ripping boy had a smash, and when we got up to him he was nearly dead, he had a two-inch piece of wood right through his head and died this morning.

Three days later, he fought the first of several combats in the B.E.2; he and his observer, Lieutenant S. A. Villiers, fired a drum and a half of Lewis gun ammunition at an enemy two-seater, but were driven off by a second one.

[26] Throughout his flying service Ball was primarily a "lone-wolf" pilot, stalking his prey from below until he drew close enough to use his top-wing Lewis gun on its Foster mounting, angled to fire upwards into the enemy's fuselage.

[24][27] According to fellow ace and Victoria Cross recipient James McCudden, "it was quite a work of art to pull this gun down and shoot upwards, and at the same time manage one's machine accurately".

[31] His singularity in dress extended to his habit of flying without a helmet and goggles, and he wore his thick black hair longer than regulations generally permitted.

[2][44] Prior to this the British government had suppressed the names of its aces—in contrast to the policy of the French and Germans—but the losses of the Battle of the Somme, which had commenced in July, made politic the publicising of its successes in the air.

[45] Ball's achievements had a profound impact on budding flyer Mick Mannock, who would become the United Kingdom's top-scoring ace and also receive the Victoria Cross.

He had it rigged to fly tail-heavy to facilitate his changing of ammunition drums in the machine-gun, and had a holster built into the cockpit for the Colt automatic pistol that he habitually carried.

Regaining an altitude of 5,000 feet (1,500 m), he tried to dive underneath an Albatros two-seater and pop up under its belly as usual, but he overshot, and the German rear gunner put a burst of 15 bullets through the Nieuport's wings and spars.

[75] While squadron armourers and mechanics repaired the faulty machine-gun synchroniser on his most recent S.E.5 mount, A8898, Ball had been sporadically flying the Nieuport again, and was successful with it on 6 May, destroying one more Albatros D.III in an evening flight to raise his tally to 44.

A German pilot officer on the ground, Lieutenant Hailer, then saw Ball's plane falling upside-down from the bottom of the cloud, at an altitude of 200 feet (61 m), with a dead prop.

[83] It is probable that Ball was not shot down at all, but had become disoriented and lost control during his final combat, the victim of a form of temporary vertigo that has claimed other pilots.

"[86] It was only at the end of the month that the Germans dropped messages behind Allied lines announcing that Ball was dead, and had been buried in Annoeullin with full military honours two days after he crashed.

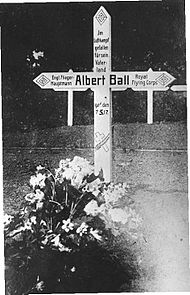

[2][87] Over the grave of the man they dubbed "the English Richthofen", the Germans erected a cross bearing the inscription Im Luftkampf gefallen für sein Vaterland Engl.

[92] On 10 June 1917, a memorial service was held for Ball in the centre of Nottingham at St Mary's Church, with large crowds paying tribute as the procession of mourners passed by.

Lloyd George wrote that "What he says in one of his letters, 'I hate this game, but it is the only thing one must do just now', represents, I believe, the conviction of those vast armies who, realising what is at stake, have risked all and endured all that liberty may be saved".

[99] Linda Raine Robertson, in The Dream of Civilised Warfare, noted that Briscoe and Stannard emphasised "the portrait of a boy of energy, pluck, and humility, a loner who placed his skill in the service of his nation, fought—indeed, invited—a personal war, and paid the ultimate sacrifice as a result", and that they "struggle to paste the mask of cheerful boyishness over the signs of the toll taken on him by the stress of air combat and the loss of friends".

[100] Alan Clark, in Aces High: The War in the Air Over the Western Front, found Ball the "perfect public schoolboy" with "the enthusiasms and all the eager intelligence of that breed" and that these characteristics, coupled with a lack of worldly maturity, were "the ingredients of a perfect killer, where a smooth transition can be made between the motives that drive a boy to 'play hard' at school and then to 'fight hard' against the King's enemies".

[101] Biographer Chaz Bowyer considered that "to label Albert Ball a 'killer' would be to do him a grave injustice", as his "sensitive nature suffered in immediate retrospect whenever he succeeded in combat".

The monument, which was commissioned by the city council and funded by public subscription,[3] consists of a bronze group on a carved pedestal of Portland stone and granite.

[110] A memorial to Ball, along with his parents, and a sister who died in infancy, appears on the exterior wall of the southwest corner of Holy Trinity Church in Lenton.

Another memorial tablet is present inside the same church, mounted on the north wall and bearing the RFC and RAF motto Per Ardua ad Astra, along with decorations of medals and royal arms.

[54]For conspicuous skill and gallantry on many occasions, notably when, after failing to destroy an enemy kite balloon with bombs, he returned for a fresh supply, went back and brought it down in flames.