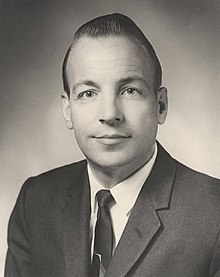

Albert Brewer

Albert Preston Brewer (October 26, 1928 – January 2, 2017) was an American lawyer and Democratic Party politician who served as the 47th governor of Alabama from 1968 to 1971.

Albert Preston Brewer was born on October 26, 1928, in Bethel Springs, Tennessee, United States, to Daniel A.

[2] From 1956 to 1963 he served as Chairman of the Decatur Planning Commission, and in 1963 he was selected as Decatur's “Outstanding Young Man of the Year” and was selected by the Alabama Junior Chamber of Commerce as one of the four “Outstanding Young Men in Alabama.”[3] Brewer married Martha Helen Farmer in 1950 and had two children, Rebecca Anne and Beverly Allison.

[9] Brewer, wary of Wallace's campaign promises to block tax increases, met with the governor to ask when he would veto the bill and send it back to the legislature.

Wallace stated that he did not intend to veto the bill to preserve his campaign pledge, instead saying that he would "just yell nigger" to avoid scrutiny.

While national Democrats balked over Johnson's exclusion, most supported the unpledged slate, which competed directly with the Republican electors.

With a coalition of Wallace supporters, organized labor, and urbanites, he overwhelmingly defeated his opponent[2] in the Democratic primary and faced no opposition in the general election.

This went into effect at the beginning of July 24, and Brewer served as acting governor for about 15 hours, meeting with some state officials, signing extradition papers, and appointing 25 honorary colonels, before Wallace was flown back to Alabama.

[15][16] Though aware of Lurleen Wallace's affliction with cancer, Brewer was not familiar with the severity of her condition until shortly before she died.

[18] Wallace's erstwhile legal counsel, Cecil Jackson, directed all executive cabinet members to offer their resignations to Brewer to allow him to build a team of his choosing.

Brewer was personally bothered by these improprieties but, wanting to seek election to his own gubernatorial term in 1970, felt it would be unwise to anger Wallace supporters by publicly exposing and denouncing these practices.

[20] As part of their attempt to quietly reform the executive branch, Brewer and Ingram tapped experienced public servants who they viewed as ethical, such as Tom Brassell, who was made assistant finance director.

At one such meeting in June 1968, Brewer called for the establishment of a state motor pool, saying he would create one by executive order and then ask for the legislature to affirm it.

[23] He also had excess copy machines sold, consolidated the state's computer systems, eliminated 12 senior assistant positions, and dispatched various staff the Wallaces' had loaned to the governor's office back to their agencies of origin to handle their official competencies.

[16] George Wallace was critical of some of the reforms, particularly the motor pool, complaining that they reflected a de facto rebuke of his late wife.

While originally cautious about besmirching the Wallaces, the complaints annoyed Brewer and led him to abandon his earlier concerns.

[27] To promote economic development, Brewer pursued industrial recruitment, traveling to New York to speak with corporate executives and hosting various in-person meetings with company representatives.

[29] In legislative and policy disputes, Brewer preferred negotiation and finding common ground rather than public spats or power plays with patronage, as George Wallace had.

[32] Several weeks after Brewer communicated to President Lyndon B. Johnson that he would engage the federal government in good faith on school segregation issues, the United States Attorney General sued in the United States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama to replace school choice options.

[33] The governor responded by engaging in similar rhetoric as segregationist, complaining of bureaucratic interference and social engineering.

More focused on education reform, Brewer decided against pushing for stronger regulations in a matter which would anger corporate interests and, in his view, earn him few additional votes in the 1970 election.

"[45] The two spoke infrequently after the meeting, and Brewer continued with his preparations to be elected as governor in his own right in 1970, and, mindful of the possibility of another Wallace candidacy, took increasingly bolder policy positions and actions.

Although earlier in his political career he was regarded as a segregationist but not a race-baiter,[48] Brewer refused to engage in racist rhetoric and courted newly registered black voters.

Wallace, whose presidential ambitions would have been destroyed with a defeat, ran a very aggressive and dirty campaign using racist rhetoric while proposing few ideas of his own.

Wallace: 50-60% 60-70% 70-80%

Brewer: 50-60% 60-70% 70-80%