Albert Gallatin

Often described as "America's Swiss Founding Father",[3][4] he was a leading figure in the early years of the United States, helping shape the new republic's financial system and foreign policy.

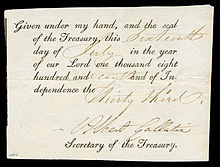

Gallatin was a prominent member of the Democratic-Republican Party, represented Pennsylvania in both chambers of Congress, and held several influential roles across four presidencies, most notably as the longest serving U.S. Secretary of the Treasury.

However, he was soon removed from office on a party-line vote due to not meeting requisite citizenship requirements; returning to Pennsylvania, Gallatin helped calm many angry farmers during the Whiskey Rebellion.

Gallatin helped Thomas Jefferson prevail in the contentious 1800 U.S. presidential election, and his reputation as a prudent financial manager led to his appointment as Treasury Secretary.

In the 1824 U.S. presidential election, Gallatin was nominated for Vice President by the Democratic-Republican Congressional caucus but never wanted the position and ultimately withdrew due to a lack of popular support.

Gallatin remained active in public life as an outspoken opponent of slavery and fiscal irresponsibility and an advocate for free trade and individual liberty.

[8][9] While attending the academy, Gallatin read deeply the philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire, along with the French Physiocrats; he became dissatisfied with the traditionalism of Geneva.

A student of the Enlightenment, he believed in the nobility of human nature and that when freed from social restrictions, it would display admirable qualities and greater results in both the physical and the moral world.

[11] Bored with monotonous Bostonian life, Gallatin and Serre set sail with a Swiss female companion to the settlement of Machias, located on the northeastern tip of the Maine frontier.

He quickly emerged as a prominent opponent of Alexander Hamilton's economic program but was declared ineligible for a seat in the Senate in February 1794 because he had not been a citizen for the required nine years prior to election.

However, with the American Revolution only a decade ended, the senators were leery of anything which might hint that they intended to establish an aristocracy, so they opened up their chamber for the first time for the debate over whether to unseat Gallatin.

In 1796, Gallatin published A Sketch on the Finances of the United States, which discussed the operations of the Treasury Department and strongly attacked the Federalist Party's financial program.

[36] As Jefferson and Madison spent the majority of the summer months at their respective estates, Gallatin was frequently left to preside over the operations of the federal government.

[38] In 1799, Gallatin made a speech advocating against normalizing relations with self-liberated slaves in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, arguing that if "they were left to govern themselves, they might become more troublesome to us, in our commerce to the West Indies, than the Algerines ever were in the Mediterranean; they might also become dangerous neighbors to the Southern States, and an asylum for renegades from those parts.

Hofstra University professor Alan Singer argued based on this speech that Gallatin "was certainly not an abolitionist" and that "his claims to oppose slavery can also be read as racist attacks on the humanity of Africans, which was not uncommon among Whites during the antebellum era".

[47] To help develop western lands, Gallatin advocated for internal improvements such as roads and canals, especially those that would connect to territories west of the Appalachian Mountains.

Resistance from many congressional Democratic-Republicans regarding cost, as well as hostilities with Britain, prevented the passage of a major infrastructure bill, but Gallatin did win funding for the construction of the National Road.

The embargo proved ineffective at accomplishing its intended purpose of punishing Britain and France, and it contributed to growing dissent in New England against the Jefferson administration.

In a letter to Jefferson, Gallatin argued that the bank was indispensable because it served as a place of deposit for government funds, a source of credit, and a regulator of currency.

In response, Gallatin sent a letter to Madison, asking for permission to resign and criticizing the president for various actions, including his failure to take a strong stance on the national bank.

[53] In 1811, Congress replaced the Non-Intercourse Act of 1809 with a law known as Macon's Bill Number 2, which authorized the president to restore trade with either France or Britain if either promised to respect American neutrality.

As with previous embargo policies pursued by the federal government under Jefferson and Madison, Macon's Bill Number 2 proved to be ineffective at halting the attacks on American shipping.

He was one of five American commissioners who would negotiate the treaty, serving alongside Henry Clay, James Bayard, Jonathan Russell, and John Quincy Adams.

The British could have chosen to shift resources to North America after the temporary defeat of Napoleon in April 1814, but, as Gallatin learned from Alexander Baring, many in Britain were tired of fighting.

[60] Gallatin's patience and skill in dealing with not only the British but also his fellow members of the American commission, including Clay and Adams, made the treaty "the special and peculiar triumph of Mr.

He has a faculty, when discussion grows too warm, of turning off its edge by a joke, which I envy him more than all his other talents; and he has in his character one of the most extraordinary combinations of stubbornness and of flexibility that I ever met with in man.

[60] Though the war with Britain had at best been a stalemate, Gallatin was pleased that it resulted in the consolidation of U.S. control over western territories, as the British withdrew their support from dissident Native Americans who had sought to create an independent state in the Great Lakes region.

He also noted that "the war has laid the foundation of permanent taxes and military establishments...under our former system we were becoming too selfish, too much attached exclusively to the acquisition of wealth...[and] too much confined in our political feelings to local and State objects.

[73] He drew upon government contacts to research Native Americans, gathering information through Lewis Cass, explorer William Clark, and Thomas McKenney of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

His research led him to conclude that the natives of North and South America were linguistically and culturally related and that their common ancestors had migrated from Asia in prehistoric times.