Albert Levitt

Attorney General Homer Cummings appointed him a judge in 1935, and arranged for him to resume his work at the Justice Department after he resigned from that position the following year.

[8] While at Harvard, he came to view Dean Roscoe Pound as his mentor, and, in part due to his romantic relationship with women's rights activist Elsie Hill, became affiliated with the National Woman's Party (NWP).

"[9] Although both Pound and Frankfurter had given Levitt advice on condition that their names not be used, NWP activists incorrectly claimed that the two had approved the text of the ERA as suitable for either legislation or constitutional amendment.

[14] While Levitt was there, in 1921, President Woodrow Wilson appointed him as a member of the annually-appointed Assay Commission, composed of citizens and officials who met at the Philadelphia Mint to test the previous year's coinage.

[19] In 1927, Levitt won a $500 first prize offered by the publisher of Theodore Dreiser's An American Tragedy for an essay on the legal and social aspects of the murder in the book.

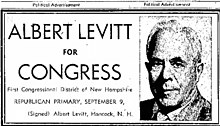

He announced in 1928 that he would challenge the incumbent Republican representative in Connecticut's 4th district, Schuyler Merritt,[23] but fell short of the necessary petition signatures to be listed on the ballot.

[24] In August 1929, Levitt began a battle to compel the Connecticut Attorney General to seek to oust the members of the Public Utilities Commission (PUC).

The Waterbury Democrat, in an editorial titled "Too much Levitt", accused him of being one of those "who continually criticize and offer no help in extracting our government from its precarious financial position".

"[41] Levitt practiced law, representing a group of Manchester residents who felt their electric rates were too high,[42] as well as an association of taxpayers seeking to reduce water pollution by Danbury.

[47] After the election, which also saw President Hoover defeated by Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt, there was immediate speculation Levitt would be rewarded for his activities against the regular Republican Party with a post in the new administration.

Hill obtained a prominent New York attorney to represent the islanders without fee, and in November 1936, Judge Levitt ruled the disenfranchisement unconstitutional under the Nineteenth Amendment.

These acts led to outcries, including from the governor of the United States Virgin Islands, Lawrence William Cramer, and from the Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes.

[64] Levitt had other conflicts with Governor Cramer, which culminated in the case of United States v. Leonard McIntosh, in which the defendant had admitted stealing government property, and a prison sentence was mandatory.

Maryland Senator Millard Tydings, its chair, knowing of Levitt's opposition and seeking to block Cramer's reappointment, invited him to testify, which he did.

[64] Levitt's appearance in January 1937 (he testified again in April) put Cummings in the position of having one of his assistants publicly oppose an appointment by Roosevelt, who had made him attorney general.

[11] Levitt's stand embarrassed Cummings, who had publicly stated that the probability of a challenge to Black's seating was so low as to be negligible, and put the attorney general in the position of having to denigrate the legal knowledge of a man he had appointed to a judgeship.

Levitt, whom The New York Times described as a "soldier of fortune, preacher, professor, corporation lawyer, Federal judge and utility 'baiter'", introduced himself to the court.

[2] After the start of World War II that year, he initially opposed the repeal of the Embargo Act, fearing that would draw the U.S. into the conflict on the side of Britain and France,[84] and in June 1940 sent a telegram to the White House demanding that Roosevelt disclose the contents of any secret agreements with the Allies to do so.

[2] After leaving that position, in April 1941, he sent Roosevelt a telegram urging him to declare war on Germany, Italy and Japan as the only way for the United States to survive.

[87] In October, Levitt appeared before a committee of the House of Representatives assailing organized labor for obstructing defense efforts, and decrying government red tape.

[2] Remaining in California, in 1945, he criticized the Dumbarton Oaks proposals, that would result in the establishment of the United Nations, for giving Britain a permanent seat on the Security Council while India, with many times its population, went without.

[99] In 1949, when Francis Cardinal Spellman accused Eleanor Roosevelt of being anti-Catholic in her writings, Levitt wrote to the cleric and alleged that he had forfeited his American citizenship and was an alien representing a foreign power, the Vatican.

Declining again to cross file, he ran on a platform of ending the Marshall Plan, cutting income taxes, and giving a weekly benefit to young people and the elderly.

He expected that his main rival in the Republican primary would be the incumbent, Democratic Senator Sheridan Downey, and stated that Nixon "hasn't a chance".

[104] Later, another fringe Republican candidate, Ulysses Grant Bixby Meyer, joined the race, but political observers gave neither man any chance.

[106] He traveled by bus through Northern California in April, and re-stated his campaign platform, which also included a return to Prohibition and forbidding public funds from being used to have a U.S. representative at the Vatican.

[108] He addressed the Republican State Convention in Fresno on April 22, and told delegates that "the three enemies of our American way of life are communism, fascism, and Vaticanism".

[125] Among the cases Levitt was involved in during his final years was a defamation suit brought by the Knights of Columbus regarding a pamphlet distributed during the 1960 presidential campaign.

[128] Though he supported Kennedy as being willing to separate his religion from his loyalty to the U.S., Levitt stated that two representatives, including House Speaker John W. McCormack, were nationals of the Vatican.

[131] In September 1967, Levitt appeared before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, opining that President Lyndon B. Johnson was violating the Constitution by prosecuting the Vietnam War and by imposing sanctions on Rhodesia.