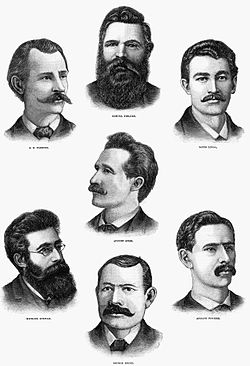

Albert Parsons

Albert Richard Parsons (June 20, 1848 – November 11, 1887) was a pioneering American socialist and later anarchist newspaper editor, orator, and labor activist.

Parsons was one of four Chicago radical leaders controversially convicted of conspiracy and hanged following a bomb attack on police remembered as the Haymarket affair.

Parsons was born June 20, 1848,[1] in Montgomery, Alabama, one of the ten children of the proprietor of a shoe and leather factory who had originally hailed from Maine.

[4] The coming of the American Civil War in 1861, or "the slave-holders' Rebellion," as he later called it, led Parsons to leave what he described as the "printer's devil": the position of newsboy.

"[4] Parsons' first military exploit was aboard the passenger steamer Morgan which ventured into the Gulf of Mexico to intercept and capture the forces of General David E. Twiggs, who had evacuated Texas en route to Washington, D.C.[4] Upon his return, Parsons sought to enlist in the regular Confederate States Army, an idea ridiculed by his employer and guardian at the time, publisher Willard Richardson of the Galveston Daily News.

[5] He hired ex-slaves to help with the harvest and netted a sufficient sum from the sale of the crop to pay for six months' tuition at Waco University, today known as Baylor, a private Baptist college.

[6] In his paper, Parsons took the unpopular position of accepting the terms of surrender and Reconstruction measures aimed at securing the political rights of former slaves.

The lately enfranchised slaves over a large section of country came to know and idolize me as their friend and defender, while on the other hand I was regarded as a political heretic and traitor by many of my former associates.

[7]In 1869, having left the printing trade, Parsons got a job as a traveling correspondent and business agent for the Houston Daily Telegraph, during which time he met Lucy Ella Gonzales (or Waller), a woman of multi-ethnic heritage.

[9] In 1870, Parsons was the beneficiary of Republican political patronage when he was appointed Assistant Assessor of United States Internal Revenue under the administration of Ulysses S.

[7] In the summer of 1873, Parsons travelled extensively through the Midwestern United States as a representative of the Texas Agriculturalist, getting a broader view of the country, deciding to settle with his wife in Chicago.

[10] Parsons attended the 2nd Convention of the SDP, held in Philadelphia from July 4–6, 1875, and was one of the group's leading English-speaking members in Chicago, joined by another able speaker, George A.

[11] As an interested observer, Parsons attended the final convention of the National Labor Union (NLU), held in Pittsburgh in April 1876.

At this convention the dying NLU divided, with its radical wing exiting to establish the Workingmen's Party of the United States — a group that soon merged with the SDP to which Parsons belonged.

[10] This organization later renamed itself the Socialist Labor Party of America at its December 1877 convention in Newark, New Jersey, which Parsons attended as a delegate.

[12] In the course of his life, Parsons ran three times for Chicago City Alderman, twice for Cook County Clerk, and once for United States Congress.

On July 21, about a week after the beginning of the strike, Parsons was called upon to address a vast throng of perhaps 30,000 workers congregated at a mass meeting on Chicago's Market Street.

With the agitated worthies present in the room audibly muttering such sentiments as "Hang him" and "Lynch him," the Chief of Police advised Parsons that his life was in danger and urged him to leave town.

He later recalled his rationale in his memoirs, written shortly before his execution in 1887: In 1879 I withdrew from all active participation in the political Labor Party, having been convinced that the number of hours per day that the wage-workers are compelled to work, together with the low wages they received, amounted to their practical disfranchisement as voters.

[20] Two years later he was also a delegate to the October 1883 convention in Pittsburgh which established the anarchist International Working People's Association, the organization to which he owed his political allegiance for the rest of his life.

Parsons avoided arrest and moved to Waukesha, Wisconsin, where he remained until June 21; afterward, he turned himself in to stand in solidarity with his comrades.

Samuel Fielden and Michael Schwab asked for clemency and their sentences were commuted to life in prison on November 10, 1887, by Governor Richard James Oglesby, who lost popularity for this decision.

In the week before his execution, The Alarm was published again for the first time since the Haymarket events, with a page 2 letter by Albert Parsons written from Prison Cell 29 on death row.

In his communique, Parsons named Dyer D. Lum as his editorial successor and offered final advice to his supporters: To other hands are now committed that task which was mine, in the work and duty, as editor of this paper.

Lay bare the inequities of capitalism; expose the slavery of law; proclaim the tyranny of government; denounce the greed, cruelty, abominations of the privileged class who riot and revel on the labor of their wage-slaves.On November 10, 1887, condemned prisoner Louis Lingg killed himself in his cell with a blasting cap hidden in a cigar.

Parsons' final words on the gallows, recorded for posterity by Dyer D. Lum in The Alarm, were: "Will I be allowed to speak, oh men of America?

A historical marker dedicated to Albert and Lucy Parsons was erected in 1997 by the City of Chicago at the location of their home, 1908 North Mohawk Street, in the Old Town neighborhood.