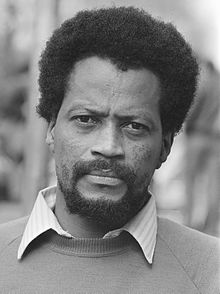

Albertina Sisulu

In the 1980s she emerged as a community leader in her hometown of Soweto, assuming a prominent role in the establishment of the UDF and the revival of the Federation of South African Women.

[5] Her interest in politics grew through her association with Walter Sisulu, a real estate agent and activist in the African National Congress (ANC), who courted and then married her.

[9] In addition, the Sisulus' home in Orlando West, a suburb of Soweto outside Johannesburg, was long-established as a meeting place for ANC leaders.

[1] She abstained from the 1952 Defiance Campaign, during which Walter was arrested and convicted of communism; in her paraphrase of the ANC's policies, "if one of the members of the family was already defying, we couldn't all go, because there were children to be looked after".

[1] On the latter occasion, she was detained for three weeks on charges of violating the pass laws, but she was ultimately acquitted, with her husband's close friend Nelson Mandela as her lawyer.

[9][14] In the early 1960s, she was involved in an ANC scheme to recruit nurses as volunteers to relocate to newly independent Tanganyika, a personal favour from Oliver Tambo to Julius Nyerere.

[1] The Minister of Law and Order allowed her fourth ban to lapse in August 1981, and she celebrated by making an address – her first political speech since the early 1960s – at a local church's commemoration of the Women's March.

[20] Nonetheless, throughout this period, Sisulu remained a prominent figure in the resistance movement, notable for her focus on civic organising on a national rather than local scale.

The funeral had taken place months earlier – on 16 January 1983 in a church in Soweto – and the charges were widely viewed as a justification to detain Sisulu ahead of the UDF's launch.

[1] However, she was also released on bail pending an appeal, allowing her to resume her political activities;[1] she said that, after several consecutive months in solitary confinement, "I came out speaking to the walls".

[5] The following year, in the aftermath of her criminal trial, she began work as receptionist and nursing assistant in Rockville, Soweto in the private surgery of Abu Baker Asvat, a doctor who was renowned for his humanitarianism.

[1] Although Asvat was a leading member of the Azanian People's Organisation, a rival of the UDF, the pair worked closely together;[25] she later said that they were like mother and son,[26] and he did not object to Sisulu's political activities, which continued in earnest.

"[27] According to historian Jonny Steinberg, other members of the community delegated Sisulu to report their concerns about Madikizela-Mandela's behaviour to the exiled ANC leadership in Lusaka, Zambia.

[27][29][30] Meanwhile, Asvat was an unpopular figure both with the state and with conservative residents of Soweto; in 1987, Sisulu was with him when he narrowly escaped a knife attack, and in December 1988, they worked without water or electricity after the supply to their surgery was cut off.

[31] Madikizela-Mandela and her Football Club long faced rumours of having arranged Asvat's assassination,[32] and Sisulu was publicly drawn into those accusations in 1997 (see below).

[35] The ensuing Pietermaritzburg Treason Trial opened on 21 October in the Natal Supreme Court with the defendants' not-guilty plea,[36] but the charges against Sisulu and 11 others were dropped on 9 December.

In June that year, she was granted her first South African passport – an abrupt reversal, given that her latest banning order had been renewed only days earlier.

[40] Later that month, she led a UDF delegation on an international tour, which included a meeting with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher.

[33] While in London, she met with Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock and addressed a major rally of the British Anti-Apartheid Movement.

[44] Meanwhile, President F. W. de Klerk's government unbanned the ANC in 1990, permitting the party to resume overt organising inside South Africa.

[47] However, she held the deputy presidency for only one term, ceding the office to Thandi Modise at the league's next national conference in December 1993.

[49] She only served one three-year term in the committee; at the 49th National Conference in December 1994, both she and her husband declined to stand for re-election to the party's leadership.

When the Houses of Parliament opened on 10 May 1994, it was Sisulu who formally nominated Mandela to serve as the first post-apartheid President of South Africa.

[53] Moreover, earlier that year, a videotaped interview with Sisulu had been included in Katiza's Journey, a BBC documentary in which journalist Fred Bridgland claimed to uncover evidence that Madikizela-Mandela had conspired to kidnap Stompie Seipei as well as to murder Asvat.

[60] The day after her testimony, Sisulu and her husband met with Desmond Tutu, the chairman of the TRC, to discuss her unhappiness at having been accused of dishonesty.

Sisulu briefly re-appeared on the witness stand, at her own request, and Ntsebeza told her that she had been "vindicated" and restored as "an icon of moral rectitude".

[61] Sisulu met her husband, Walter, in 1941, and their families agreed on lobola the following year; they married on 15 July 1944 in a civil ceremony in Cofimvaba.

[66]On 10 October 1989, Sisulu was visiting Mandela at Victor Verster Prison when she learned of her husband's impending release through an SABC broadcast.

In 2007, the Gauteng Provincial Government announced that it would rename the R21 highway between Pretoria and the O. R. Tambo International Airport as the Albertina Sisulu Freeway.

As part of this programme, the South African Post Office launched a commemorative stamp,[100][101] and a rare species of orchid, brachycorythis conica subsp.