Alberto Fujimori

His administration, marked by what became known as "Fujishock", rapidly stabilized the economy and defeated the Maoist insurgency of Sendero Luminoso, but at the cost of severe authoritarian measures, including the 1992 self-coup, widespread human rights abuses, and entrenched corruption.

This dual legacy continues to polarize Peruvian society, with many crediting him for rescuing the nation from collapse, while others condemn his repressive tactics and the long-term social inequalities from his policies.

[28][30] During the second round of elections, Fujimori originally received support from left-wing groups and those close to the García government, exploiting the popular distrust of the existing Peruvian political establishment and the uncertainty about the proposed neoliberal[neutrality is disputed] economic reforms of his opponent, novelist Mario Vargas Llosa.

[34] According to news magazine Oiga, the armed forces finalized plans on 18 June 1990 involving multiple scenarios for a coup d'état to be executed on 27 July 1990, the day prior to Fujimori's inauguration.

[37] After taking office, Fujimori abandoned the economic platform he promoted during his campaign, adopting more aggressive neoliberal[neutrality is disputed] policies than those espoused by Vargas Llosa, his opponent in the election.

[52] Without political obstacles, the military was able to implement the objectives outlined in the Plan Verde[28][50][35] while Fujimori served as president to project an image that Peru was supporting a liberal democracy.

[60] Two weeks after the self-coup, the George H. W. Bush administration changed its position and officially recognized Fujimori as the legitimate leader of Peru, partly because he was willing to implement economic austerity measures, but also because of his adamant opposition to the Shining Path.

Prior to his reforms, the country suffered from hyperinflation that, at its peak, approached levels as high as 7,500% annually, while fiscal deficits were estimated to be in the range of 8–9% of GDP, and exports were roughly US$4 billion.

[84][85] While these policies are widely credited with restoring macroeconomic stability and jumpstarting growth in a previously battered economy, they also contributed to heightened income inequality and social disparities.

[86] Fujimori was accused of a series of offences, including embezzlement of public funds, abuse of power, and corruption during almost 10 years as president (1990–2000), especially when he gained greater control after the self-coup.

[88] One of those responsible for maintaining an image of apparent honesty and government approval was Vladimiro Montesinos, head of the National Intelligence Service (SIN), who systematically bribed politicians, judges, and the media.

That criminal network also involved authorities of his government; furthermore, due to privatisation and the arrival of foreign capital, companies close to the Ministry of the Economy and Finance were allowed to use state money for public works tenders, as in the cases of AeroPerú, JJC Contratistas Generales (of the Camet Dickmann family), and the Banco de Crédito.

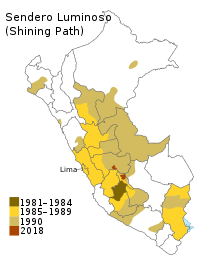

In 1989, 25% of Peru's district and provincial councils opted not to hold elections, owing to a persistent campaign of assassination, over the course of which over 100 officials had been killed by the Shining Path in that year alone.

[91] By the early 1990s, some parts of the country were under the control of the insurgents, in territories known as "zonas liberadas" ("liberated zones"), where inhabitants lived under the rule of these groups and paid them taxes.

[93] Two previous governments, those of Fernando Belaúnde Terry and Alan García, at first neglected the threat posed by the Shining Path, then launched an unsuccessful military campaign to eradicate it, undermining public faith in the state and precipitating an exodus of elites.

The final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, published on 28 August 2003, noted that the armed forces were also guilty of destroying villages and murdering countryside inhabitants whom they suspected of supporting insurgents.

The government rejected the militants' demand to release imprisoned MRTA members and secretly prepared an elaborate plan to storm the residence, while stalling by negotiating with the hostage-takers.

[105] Images of President Fujimori at the ambassador's residence during and after the military operation, surrounded by soldiers and liberated dignitaries, and walking among the corpses of the insurgents, were widely televised.

[108] The success of the military operation in the Japanese embassy hostage crisis was tainted by subsequent allegations that at least three and possibly eight of the insurgents were summarily executed by the commandos after surrendering.

[123] In April 2009, Fujimori was convicted of human rights violations and sentenced to 25 years imprisonment for his role in kidnappings and murders by the Grupo Colina death squad during his government's battle against the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement in the 1990s.

[151] In November, Congress approved an investigation of Fujimori's involvement in the airdrop of Kalashnikov rifles into the Colombian jungle in 1999 and 2000 for guerrillas of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC).

He hoped to participate in the 2006 presidential elections, but in February 2004, the Constitutional Court dismissed this possibility, because the ex-president was specifically barred by Congress from holding any office for ten years.

Fujimori saw the decision as unconstitutional, as did his supporters such as former congress members Luz Salgado, Martha Chávez and Fernán Altuve, who argued it was a "political" maneuver and that the only body with the authority to determine the matter was the National Elections Jury (JNE).

[171] He faced a third trial in July 2009 over allegations that he illegally gave US$15 million in state funds to Vladimiro Montesinos, former head of the National Intelligence Service, during the two months prior to his fall from power.

[176] In July 2016, with three days left in his term, President Humala said that there was insufficient time to evaluate a second request to pardon Fujimori, leaving the decision to his successor Pedro Pablo Kuczynski.

[186] Two months before his death, on 14 July 2024, Keiko Fujimori announced her father's candidacy for the 2026 Peruvian general election, despite his legal impediments and difficulties related to old age and poor health.

[192] On 11 September, several Fujimorist members of congress wearing black, along with a priest, arrived at the home of Fujimori's daughter Keiko in Lima's San Borja District, amid reports that his health was failing.

[202][203] Jorge del Castillo, Mauricio Mulder, Luis Galarreta, Miguel Torres, former Foreign Minister Javier Gonzáles-Olaechea and Alberto Otárola were also present at the funeral,[202][204] as well as the singer Melcochita.

[219][220] International media described him following his death as an "authoritarian" who was "divisive", and whose "heavy handed" tactics "created a negative legacy" in Peru that frustrated his eldest daughter's attempts to be elected to the presidency.

[224] Yoshimasa Hayashi, Chief Cabinet Secretary of Japan, expressed his condolences to Fujimori's family, citing his role in resolving the Japanese embassy hostage crisis.