Alexander II Zabinas

Thus, in 124 BC an alliance was established between Egypt and Cleopatra Thea, now ruling jointly with Antiochus VIII, her son by Demetrius II.

Alexander II was defeated, and he escaped to Antioch, where he pillaged the temple of Zeus to pay his soldiers; the population turned against him, and he fled and was eventually captured.

Seleucus IV's legitimate heir, Demetrius I, was a hostage in Rome,[note 1] and his younger son Antiochus was declared king.

[18] The Parthians freed Demetrius II to put pressure on Antiochus VII, who was killed in 129 BC during a battle in Media.

[note 4][27] The first century historian Josephus wrote the Syrians themselves asked Ptolemy VIII to send them a Seleucid prince as their king, and he chose Alexander II.

[38] Modern historic research prefers the detailed account of Justin regarding Alexander II's claims of paternity and his connection to Antiochus VII.

[44] The surname of Alexander II has different spellings; it is "Zabinaeus" in the prologue of the Latin language Philippic Histories, book XXXIX.

[45] Zabinas is a Semitic proper name,[35] derived from the Aramaic verb זבן (pronounced Zabn), which means "buy" or "gain".

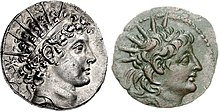

[27] In the view of archaeologist Jean-Antoine Letronne, who agreed that Alexander II was an imposter, a coin meant for the public could not have had "Zabinas" inscribed on it as it is derisory.

[38] Alexander the Great (d. 323 BC), founder of the Macedonian Empire, was an important figure in the Hellenistic world; his successors used his legacy to establish their legitimacy.

[note 11][77] The radiate crown was utilised for the first time at an unknown date by Antiochus IV, who chose Hierapolis-Bambyce, the most important sanctuary of Atargatis, to ritually marry Diana, considered a manifestation of the Syrian goddess in the Levant.

[42] It is possible that, by utilising Dionysus, the son of the supreme god, Alexander II presented himself as the spiritual successor of his god-father, in addition to being his political heir.

Burying the fallen king earned Alexander II the acclaim of Antioch's citizens;[note 12][36] it was probably a calculated move aiming at gaining the support of Antiochus VII's loyal men.

[80] The seventh century chronicler John of Antioch wrote that following Antiochus VII's death, his son Seleucus ascended the throne and was quickly deposed by Demetrius II and fled to Parthia.

Historian Auguste Bouché-Leclercq criticised this account, which is problematic and could be a version of Demetrius II's Parthian captivity corrupted by John of Antioch.

[45] According to Diodorus Siculus, Alexander II was "kindly and of a forgiving nature, and moreover was gentle in speech and in manners, wherefore he was deeply beloved by the common people".

[98] Demetrius II asked for temple asylum in Tyre, but was killed by the city's commander (praefectus) in the spring or summer of 125 BC.

[note 19][62] Under Antiochus VII, the Judean high-priest and ruler John Hyrcanus I acquired the status of a vassal prince, paying tribute and minting his coinage in the name of the Syrian monarch.

[107] The 127 BC embassy sent by Judea to Rome asked the senate to force the Syrian abandonment of: Jaffa, the Mediterranean harbours which included Iamnia and Gaza, the cities of Gazara and Pegae (near Kfar Saba), in addition to other territories taken by King Antiochus VII.

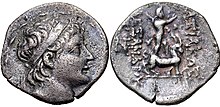

[note 21][113] The earliest series of coins minted by the high priest showed the Greek letter Α (alpha) positioned prominently above John Hyrcanus I's name.

The alpha must have been the first letter of a Seleucid king's name, and many scholars, such as Dan Barag, suggested that it represents Alexander II.

[116] The high priest eventually won the independence of Judea later in Alexander II's reign;[113] once John Hyrcanus I severed his ties with the Seleucids, the alpha was removed.

[119] In Ptolemais, Cleopatra Thea refused to recognise Alexander II as king; already in 187 SE (126/125 BC), the year of her husband's defeat, she struck tetradrachms in her own name as the sole monarch of Syria.

This led Cleopatra Thea to choose her younger son by Demetrius II, Antiochus VIII, as a co-ruler in 186 SE (125/124 BC).

[121] Justin stated that Ptolemy VIII's reason for abandoning Alexander II was the latter's increased arrogance swelled by his successes that led him to treat his benefactor with insolence.

[122] The change of Ptolemaic policy probably had less to do with Ptolemy VIII's pride than with Alexander II's victories; a strong neighbour in Syria was not a desired situation for Egypt.

Earlier numismatists, such as Edward Theodore Newell and Ernest Babelon, who only knew about the 125 BC stater, suggested that it was minted with the gold pillaged from the temple.

However, the iconography of that stater does not match that used for Alexander II's late coinage, as the diadem ties fall in a straight fashion on the neck.

[note 24][62] Though his last coins were issued in 190 SE (123/122 BC), ancient historians do not provide the explicit date of Alexander II's death.

[126] According to Diodorus Siculus, many who witnessed the king's end "remarked in various ways on the fickleness of fate, the reversals in human fortunes, the sudden turns of tide, and how changeable life could be, far beyond what anyone would expect".