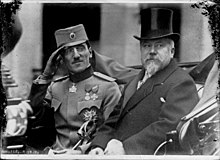

Alexander I of Yugoslavia

In 1918, Alexander oversaw the unification of Serbia and the former Austrian provinces of Croatia-Slavonia, Slovenia, Vojvodina, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Dalmatia into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes on the basis of the Corfu Declaration.

During a stop in Marseille, he was assassinated by Vlado Chernozemski, a member of the pro-Bulgarian Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, which received assistance from the Croat Ustaše led by Ante Pavelić.

Despite enjoying support from the Russian Empire, at the time of Alexander's birth and early childhood, the House of Karađorđević was in political exile, with family members scattered all over Europe, unable to return to Serbia.

The British historian Robert Seton-Watson described Alexander as becoming a Russophile during his time in Petrograd, feeling much gratitude for the willingness of the Russian Emperor Nicholas II to give him a refuge, where he was treated with much honor and respect.

[9] Following pressure from powerful figures such as Prime Minister Nikola Pašić and high-ranking officers Dragutin "Apis" Dimitrijević and Petar Živković,[citation needed] George publicly renounced his claim to the throne in March of that year in favour of Alexander.

They all agreed to end all internal conflicts in the Royal Serbian Army and fully commit to realizing national goals, which allowed space for consolidation before the two successive Balkan Wars.

[24] However, the Serbian Army suffered major shortages of equipment with a third of the men called up in August 1914 having no rifles or ammunition, and new recruits being advised to bring their own boots and clothing as there were no uniforms for them.

[25] Field Marshal Radomir Putnik persuaded Crown Prince Alexander and King Peter that it was better to keep the Serbian Army intact to one day liberate Serbia rather to stand and fight in Kosovo as many Serb officers wanted.

In the fall of 1916, Alexander's long-standing dispute with the secret military society of the Black Hand came to ahead, when Colonel Dimitrijević began to openly criticize his leadership.

[32] On 25 February 1919, Alexander signed a land reform decree breaking up all feudal estates over the size of 100 cadastral yokes with compensation to be paid for the former landowners except for those who belonged to the House of Habsburg and the other ruling families of enemy states in the Great War.

[34] Seton-Watson described Alexander as having an "autocratic" personality, a man who was first and foremost a soldier who spent "six of his formative years" in the Serbian Army, which left him with a "military outlook which unfitted him to deal with the delicate problems of constitutional government and which made compromise hard for him".

He was said to have wished to marry Grand Duchess Tatiana Nikolaevna of Russia, a cousin of his wife and the second daughter of Tsar Nicholas II, and was distraught by her untimely death in the Russian Civil War.

The Russophile Alexander was horrified by the murders of the House of Romanov-including the Grand Duchess Tatiana-and during his reign was very hostile towards the Soviet Union, welcoming Russian emigres to Belgrade.

[45] Alexander appointed the Slovene Catholic priest, Father Anton Korošec prime minister with one mandate, namely to stop the slide towards civil war.

[46] On 1 December 1928, the lavish celebrations of the 10th anniversary of the founding of the triune Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes that the government organized led to rioting that left 10 dead in Zagreb.

[46] Alexander tried to promote a sense of Yugoslav identity by always taking his vacations in Slovenia, naming his second son after a Croat king, and being a godfather to a Bosnian Muslim child.

[51] The British historian Richard Crampton wrote many Serbs "...were alienated by the attempt, albeit unsuccessful, to lessen the Serbian domination on which, to add insult to injury, many of the faults of the previous system were blamed.

[51] The royal dictatorship was seen in Croatia as merely a form of Serbian domination, and one result was a marked upswing in support for fascistic Ustashe, which advocated winning Croat independence via violence.

[53] In response to pressure from Yugoslavia's allies, especially France and Czechoslovakia, led Alexander to decide to lessen the royal dictatorship by bringing in a new constitution which allowed the skupština to meet again.

The 1931 constitution kept Yugoslavia as a unitary state, which enraged the non-Serbian peoples who demanded a federation and saw Alexander's royal dictatorship as thinly disguised Serbian domination.

[51] In response to the impoverishment of the countryside caused by the Great Depression, Alexander reaffirmed in a speech the right of every peasant family to a minimum amount of land that could not be seized by a bank in the event of a debt default.

[58] Despite his distaste for communism, the King gave support, albeit in a very cautious and hesitant way, to the plans of French Foreign Minister Louis Barthou to bring the Soviet Union into a front meant to contain Germany.

After the Ustaše's Velebit uprising in November 1932, Alexander said through an intermediary to the Italian government, "If you want to have serious riots in Yugoslavia or cause a regime change, you need to kill me.

"[59] The French Foreign Minister Louis Barthou had attempted in 1934 to build an alliance meant to contain Germany, consisting of France's allies in Eastern Europe like Yugoslavia, together with Italy and the Soviet Union.

The body of the chauffeur Foissac, who had been mortally wounded, slumped and jammed against the brakes of the car, which allowed the cameraman to continue filming from within inches of the King for a number of minutes afterwards.

The IMRO was a political organization that fought for the liberation of the occupied region of Macedonia and its independence, initially as some form of second Bulgarian state, followed by a later unification with the Kingdom of Bulgaria.

[76] An investigation by the French police quickly established that the assassins had been trained and armed in Hungary; had travelled to France on forged Czechoslovak passports; and frequently telephoned Ustaše leader Ante Pavelić, who was living in Italy.

[78] Both London and Paris made it clear that they regarded Mussolini as a responsible European statesman and in private told Belgrade that under no circumstances would they allow Il Duce to be blamed.

The Holy See gave special permission to bishops Aloysius Stepinac, Antun Akšamović, Dionisije Njaradi, and Gregorij Rožman to attend the funeral in an Orthodox church.

In the coming years, Prince Paul (as regent) attempted to keep a neutral balance between London and Berlin until 1941, when he yielded to heavy pressure to join the Tripartite Pact.