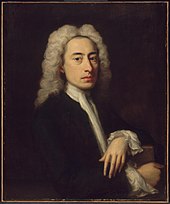

Alexander Pope

An exponent of Augustan literature,[2] Pope is best known for his satirical and discursive poetry including The Rape of the Lock, The Dunciad, and An Essay on Criticism, and for his translations of Homer.

Pope is often quoted in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, some of his verses having entered common parlance (e.g. "damning with faint praise" or "to err is human; to forgive, divine").

Pope's education was affected by the recently enacted Test Acts, a series of English penal laws that upheld the status of the established Church of England, banning Catholics from teaching, attending a university, voting, and holding public office on penalty of perpetual imprisonment.

One of them, John Caryll (the future dedicatee of The Rape of the Lock), was twenty years older than the poet and had made many acquaintances in the London literary world.

[7] From the age of 12 he suffered numerous health problems, including Pott disease, a form of tuberculosis that affects the spine, which deformed his body and stunted his growth, leaving him with a severe hunchback.

His tuberculosis infection caused other health problems including respiratory difficulties, high fevers, inflamed eyes and abdominal pain.

Around 1711, Pope made friends with Tory writers Jonathan Swift, Thomas Parnell and John Arbuthnot, who together formed the satirical Scriblerus Club.

These events led to an immediate downturn in the fortunes of the Tories, and Pope's friend Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke, fled to France.

[12] The money made from his translation of Homer allowed Pope to move in 1719 to a villa at Twickenham, where he created his now-famous grotto and gardens.

The serendipitous discovery of a spring during the excavation of the subterranean retreat enabled it to be filled with the relaxing sound of trickling water, which would quietly echo around the chambers.

At the time the poem was published, its heroic couplet style was quite a new poetic form and Pope's work an ambitious attempt to identify and refine his own positions as a poet and critic.

It was said to be a response to an ongoing debate on the question of whether poetry should be natural, or written according to predetermined artificial rules inherited from the classical past.

A mock-epic, it satirises a high-society quarrel between Arabella Fermor (the "Belinda" of the poem) and Lord Petre, who had snipped a lock of hair from her head without permission.

[17] The revised, extended version of the poem focuses more clearly on its true subject: the onset of acquisitive individualism and a society of conspicuous consumers.

Though a masterpiece due to having become "one of the most challenging and distinctive works in the history of English poetry", writes Mack, "it bore bitter fruit.

It brought the poet in his own time the hostility of its victims and their sympathizers, who pursued him implacably from then on with a few damaging truths and a host of slanders and lies.

"My brother does not seem to know what fear is," she told Joseph Spence, explaining that Pope loved to walk alone, so went accompanied by his Great Dane Bounce, and for some time carried pistols in his pocket.

[20] This first Dunciad, along with John Gay's The Beggar's Opera and Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels, joined in a concerted propaganda assault against Robert Walpole's Whig ministry and the financial revolution it stabilised.

Although Pope was a keen participant in the stock and money markets, he never missed a chance to satirise the personal, social and political effects of the new scheme of things.

[24] The poem is an affirmative statement of faith: life seems chaotic and confusing to man in the centre of it, but according to Pope it is truly divinely ordered.

Pope used the model of Horace to satirise life under George II, especially what he saw as the widespread corruption tainting the country under Walpole's influence and the poor quality of the court's artistic taste.

Pope added as an introduction to Imitations a wholly original poem that reviews his own literary career and includes famous portraits of Lord Hervey ("Sporus"), Thomas Hay, 9th Earl of Kinnoull ("Balbus") and Addison ("Atticus").

Pope secured a revolutionary deal with the publisher Bernard Lintot, which earned him 200 guineas (£210) a volume, a vast sum at the time.

[37] In 1726, the lawyer, poet and pantomime-deviser Lewis Theobald published a scathing pamphlet called Shakespeare Restored, which catalogued the errors in Pope's work and suggested several revisions to the text.

The poet and his family were Catholics and so fell subject to the prohibitive Test Acts, which hampered their co-religionists after the abdication of James II.

[39][40] As a child Pope survived once being trampled by a cow, but when he was 12 he began struggling with tuberculosis of the spine (Pott disease), which restricted his growth, so that he was only 4 feet 6 inches (1.37 metres) tall as an adult.

A kind of poetic manifesto in the vein of Horace's Ars Poetica, it met with enthusiastic attention and won Pope a wider circle of prominent friends, notably Joseph Addison and Richard Steele, who had recently begun to collaborate on the influential The Spectator.

Though Pope never married, about this time he became strongly attached to Lady M. Montagu, whom he indirectly referenced in his popular Eloisa to Abelard, and to Martha Blount, with whom his friendship continued through his life.

As a satirist, Pope made his share of enemies as critics, politicians and certain other prominent figures felt the sting of his sharp-witted satires.

At this time Lewis Theobald was replaced with the Poet Laureate Colley Cibber as "king of dunces", but his real target remained the Whig politician Robert Walpole.