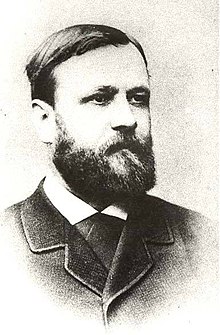

Alexandru Lambrior

Lambrior compiled a successful anthology of texts covering some three centuries, and his work on early literature existed alongside an interest in folklore, about which he also proposed original theories.

His mother Marghiolița was the daughter of a low-ranking boyar: her father Vasile Cumpătă was vistiernic (treasury official) who owned a large estate in Soci village.

By 1848, Dimitrachi had become a pitar (bread supplier), but he died later that year, and Marghiolița followed in 1850, leaving five-year-old Alexandru and his younger sister orphans; he was subsequently raised by various relatives, first at his grandparents' and then in Flămânzi.

[1] The May 1871 firing, which involved a number of teachers in several cities and was carried out by Education Minister Cristian Tell, prompted all but two of the faculty at Laurian to resign within two days and sparked ample but ultimately futile protests.

[1] Already from mid-1876, the National Liberal Education Minister Gheorghe Chițu was threatening to cut off his scholarship, suspecting that Lambrior, who was submitting letters to the rival Conservatives' Timpul, was more interested in politics than in his studies.

He clung desperately to life, perturbed by thoughts for his family: in 1869, he had married Maria, the daughter of Huși Major Manolache Cișman, and the couple had three sons aged seven to twelve.

[9] As a philologist, Lambrior made a name for himself in 1873, when he published a study about old and modern Romanian, which became a representative text for Junimea's approach to language issues.

While praising the translators for the accuracy of their expression, he deplored their avoidance of older words in favor of newer terms, which he felt could never be in harmony with the rest of the language.

[13] In 1880–1881, he was among the first philologists to argue that Coresi played a leading role in the literary language's development, and that the first translations of religious texts in Transylvania "extinguished" local written dialects in the other Romanian provinces of Moldavia and Wallachia.

Later philologists such as Nicolae Iorga, Ovid Densusianu, Rosetti and Petre P. Panaitescu embraced the idea, which was only given a critical re-evaluation by Ion Gheție in the 1980s.

The third such collection, after those of Timotei Cipariu and Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu, it includes a preface where the author mentions his didactic as well as aesthetic scope, opining that "the true Romanian language" is best learned by "reading and re-reading well-written fragments".

He was the first Romanian folklorist to argue in favor of assembling a corpus of folk literature by recording all variants and types in their authentic form, with the goal of precisely understanding the people's ideas, beliefs, spirit and literary inclinations.

[1] In many areas a pioneer, the judgment of George Călinescu became increasingly valid as the 20th century progressed: "his small number of philological publications is remembered with veneration, but never consulted.

He believed that his own century had witnessed the uprooting of the first and the exposure of the second to increasing influence by the educated class, threatening the production and transmission of folklore.

He suggested that the genre was initially sung at gatherings of the elite and that for the Romanian nobility of the period, it represented the highest form of verbal art.