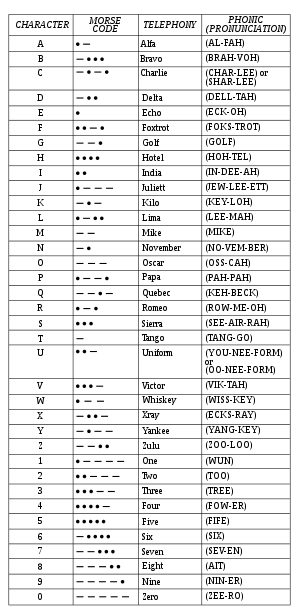

NATO phonetic alphabet

[1] The 26 code words are as follows (ICAO spellings): Alfa, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, Echo, Foxtrot, Golf, Hotel, India, Juliett, Kilo, Lima, Mike, November, Oscar, Papa, Quebec, Romeo, Sierra, Tango, Uniform, Victor, Whiskey, X-ray, Yankee, and Zulu.

[Note 1] ⟨Alfa⟩ and ⟨Juliett⟩ are spelled that way to avoid mispronunciation by people unfamiliar with English orthography; NATO changed ⟨X-ray⟩ to ⟨Xray⟩ for the same reason.

A 1955 NATO memo stated that: It is known that [the spelling alphabet] has been prepared only after the most exhaustive tests on a scientific basis by several nations.

One of the firmest conclusions reached was that it was not practical to make an isolated change to clear confusion between one pair of letters.

[3]Soon after the code words were developed by ICAO (see history below), they were adopted by other national and international organizations, including the ITU, the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the United States Federal Government as Federal Standard 1037C: Glossary of Telecommunications Terms[4] and its successors ANSI T1.523-2001[5] and ATIS Telecom Glossary (ATIS-0100523.2019)[6] (all three using the spellings "Alpha" and "Juliet"), the United States Department of Defense,[7] the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) (using the spelling "Xray"), the International Amateur Radio Union (IARU), the American Radio Relay League (ARRL), the Association of Public-Safety Communications Officials-International (APCO), and by many military organizations such as NATO (using the spelling "Xray") and the now-defunct Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO).

NATO uses the regular English numerals (zero, one, two, etc., though with some differences in pronunciation), whereas the ITU (beginning on 1 April 1969)[8] and the IMO created compound code words (nadazero, unaone, bissotwo etc.).

The potential for confusion increases if static or other interference is present, as is commonly the case with radio and telephonic communication.

Most major airlines use the alphabet to communicate passenger name records (PNRs) internally, and in some cases, with customers.

The final choice of code words for the letters of the alphabet and for the digits was made after hundreds of thousands of comprehension tests involving 31 nationalities.

The ICAO, NATO, and FAA use modifications of English digits as code words, with 3, 4, 5 and 9 being pronounced tree, fower (rhymes with lower), fife and niner.

For directions presented as the hour-hand position on a clock, the additional numerals "ten", "eleven" and "twelve" are used with the word "o'clock".

[15] There are two IPA transcriptions of the letter names, from the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the Deutsches Institut für Normung (DIN).

The resulting alphabet was adopted by the International Commission for Air Navigation, the predecessor of the ICAO, and was used for civil aviation until World War II.

To enable the US, UK, and Australian armed forces to communicate during joint operations, in 1943 the CCB (Combined Communications Board; the combination of US and UK upper military commands) modified the US military's Joint Army/Navy alphabet for use by all three nations, with the result being called the US-UK spelling alphabet.

The CCBP (Combined Communications Board Publications) documents contain material formerly published in US Army Field Manuals in the 24-series.

Major F. D. Handy, directorate of Communications in the Army Air Force (and a member of the working committee of the Combined Communications Board), enlisted the help of Harvard University's Psycho-Acoustic Laboratory, asking them to determine the most successful word for each letter when using "military interphones in the intense noise encountered in modern warfare."

[25]After World War II, with many aircraft and ground personnel from the allied armed forces, "Able Baker" was officially adopted for use in international aviation.

From 1948 to 1949, Jean-Paul Vinay, a professor of linguistics at the Université de Montréal, worked closely with the ICAO to research and develop a new spelling alphabet.

NATO was in the process of adopting the ICAO spelling alphabet, and apparently felt enough urgency that it adopted the proposed new alphabet with changes based on NATO's own research, to become effective on 1 January 1956,[27] but quickly issued a new directive on 1 March 1956[28] adopting the now official ICAO spelling alphabet, which had changed by one word (November) from NATO's earlier request to ICAO to modify a few words based on US Air Force research.

[10] The final version given in the table above was implemented by the ICAO on 1 March 1956,[11] and the ITU adopted it no later than 1959 when they mandated its usage via their official publication, Radio Regulations.

[citation needed] In the official version of the alphabet,[31] two spellings deviate from the English norm: Alfa and Juliett.

The alphabet is defined by various international conventions on radio, including: [45][42] For the 1938 and 1947 phonetics, each transmission of figures is preceded and followed by the words "as a number" spoken twice.

However, there is occasional regional substitution of a few code words, such as replacing them with earlier variants, to avoid confusion with local terminology.