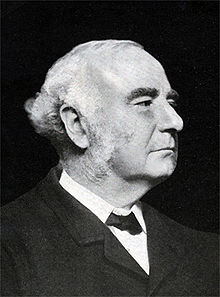

Alfred Newton

Among his numerous publications were a four-volume Dictionary of Birds (1893–6), entries on ornithology in the Encyclopædia Britannica (9th edition)[1] while also an editor of the journal Ibis from 1865 to 1870.

After the Newtons left, Elveden Hall and its estate were bought by Prince Duleep Singh in 1863, and later by the Guinness family (Earl of Iveagh).

[5] In 1828 the Newton family made a trip to Italy, and on the way back Alfred was born on 11 June 1829 at Les Délices, a chateau near Geneva.

[6][4] As a youth Newton shot game birds – black or red grouse, common pheasant, partridge.

Those included the great bustard (Otis tarda), Montagu's harrier (Circus pygargus), ravens, buzzards (Buteo sp.

"The vast warrens of the 'Breck', the woods and water-meadows of the valley of the Little Ouse, and the neighbouring Fenland made an ideal training-ground for a naturalist".

[16] Newton was one of the first zoologists to accept and champion the views of Charles Darwin, and his early lecture courses as professor were on evolution and zoogeography.

[21] The specific epithet of Genyornis newtoni, a prehistoric bird described in 1896 by Edward Charles Stirling and A. H. C. Zietz, commemorates this author.

His letters to The Times and addresses to the British Association for the Advancement of Science meetings on this subject were regularly reprinted as pamphlets by the Society.

He made efforts to clarify that his motivations for conservation were scientific and that these were distinct from sentiments influenced by earlier movements against animal cruelty and vivisection.

[26][27] The Cambridge University Museum of Zoology contains a significant amount of material from Newton, including specimens collected in Madagascar, Polynesia, South America and the Caribbean, eggs, books and correspondence.

[28] Newton's correspondence gives an intimate view of how he encountered the momentous idea of evolution by means of natural selection: Not many days after my return home there reached me the part of the Journal of the Linnean Society which bears on its cover the date 20th August 1858, and contains the papers by Mr Darwin and Mr Wallace, which were communicated to that Society at its special meeting of the first of July preceding...

[25] The British Association annual meeting for 1860, held in the University Museum in Oxford, was the location for one of the most important public debates in 19th century biology.

Section we had another hot Darwinian debate... After [lengthy preliminaries] Huxley was called upon by Henslow to state his views at greater length, and this brought up the Bp.

who made so ill an use of his wonderful speaking powers to try and burke, by a display of authority, a free discussion on what was, or was not, a matter of truth, and reminded him that on questions of physical science 'authority' had always been bowled out by investigation, as witness astronomy and geology.He then caught hold of the Bp's assertions and showed how contrary they were to facts, and how he knew nothing about what he had been discoursing on.

Ever since 1857 when Richard Owen presented (to the Linnean Society) his view that man was marked off from all other mammals by possessing features of the brain peculiar to the genus Homo, Huxley had been on his trail.

At the 1862 Cambridge meeting Huxley arranged for his friend William Flower to give a public dissection to show that the same structures were indeed present, not only in apes, but in monkeys also.

In a letter to his brother Newton wrote: There was a grand kick-up again between Owen and Huxley, the former struggling against facts with a devotion worthy of a better cause.