Alfred and Emily

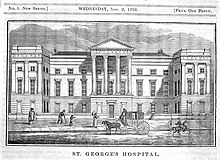

At the end of part one, there is an explanatory section written from an authorial perspective, followed by two portraits of a man and an encyclopaedic entry[1] about the hospital that Emily worked in.

The second part of the book transports Alfred and Emily to the stage in their married life when they were farming, unhappily, in Southern Rhodesia.

She concluded with praise: "In its generosity of spirit, its shaped and contained fury, Alfred and Emily is also an extraordinary, unconventional addition to Lessing’s autobiography.

"[5] Valerie Sayers in The Washington Post saw Alfred and Emily as proving Lessing's "ongoing interest in formal experimentation", in this case finding "two ingenious forms".

Instead, she holds that the second part is a precious piece of literature that deserves a reader's attention because Lessing reworks her longstanding topics masterfully, and with a loving gesture towards her otherwise hated mother.

Other reasons include that she finds the novella's narrative not compelling since "memorial commentary dispels the invented world" by interrupting it with a couple of prolepses, to the effect that "the temporal now of fiction is dislodged.

"[2] Judith Kegan Gardiner thinks that in Alfred and Emily Lessing's "deliberate teasing of the readers' desires to collapse fiction into autobiography" is "even more striking" than in The Golden Notebook.

"[9] Last but not least, here is a statement that may be taken to illustrate hybridity in yet another shape: ″Alfred and Emily is unusual in being both fiction and non-fiction at once: the same story told in two different ways – a double throw of the dice″, finds Blake Morrison in his review in The Guardian.