Algerian Civil War

Algerian government victory Armed Islamic Group (from 1993)Minor involvement: Sudan (alleged)[7][8][9] Iran (alleged)[7][8][9]Egyptian Islamic Jihad (until 1995)[10] Abdelhak Layada (POW) Djafar al-Afghani † Cherif Gousmi † Djamel Zitouni † Antar Zouabri † Armed Forces PoliceGendarmerieState SecurityLocal militias[13] Escalation 1994–1996 Massacres and reconciliation 1996–1999 Defeat of the GIA 1999–2002 The Algerian Civil War (Arabic: الحرب الأهلية الجزائرية), known in Algeria as the Black Decade (Arabic: العشرية السوداء, French: La décennie noire),[17] was a civil war fought between the Algerian government and various Islamist rebel groups from 11 January 1992 (following a coup negating an Islamist electoral victory) to 8 February 2002.

[28][29] Social conditions that led to dissatisfaction with the FLN government, and interest in jihad against it include: a population explosion in the 1960s and 70s that outstripped the stagnant economy's ability to supply jobs, housing, food and urban infrastructure to massive numbers of young in the urban areas;[Note 2] a collapse in the price of oil,[Note 3] whose sale supplied 95% of Algeria's exports and 60% of the government's budget;[30] a single-party state ostensibly based on Arab socialism, anti-imperialism, and popular democracy, but ruled by high-level military and consisting primarily of French-speaking clans from the east side of the country;[30] "corruption on a grand scale";[30] underemployed Arabic-speaking college graduates frustrated that the "Arab language fields of law and literature took a decisive back seat to the French-taught scientific fields in terms of funding and job opportunities";[32] and in response to these issues, "the most serious riots since independence" occurring in October 1988 when thousands of urban youth (known as hittistes) took control of the streets despite the killing of hundreds by security forces.

[33] In the 1980s the government imported two renowned Islamic scholars, Mohammed al-Ghazali and Yusuf al-Qaradawi, to "strengthen the religious dimension" of the ruling National Liberation Front (FLN) party's "nationalist ideology".

Abbassi Madani—a professor at University of Algiers and ex-independence fighter—represented a relatively moderate religious conservatism and symbolically connected the party to the Algerian War of Independence, the traditionally emphasized source of the ruling FLN's legitimacy.

Its doctors, nurses and rescue teams showed "devotion and effectiveness" helping victims of an earthquake in Tipaza Province;[38] its organized marches and rallies "applied steady pressure on the state" to force a promise of early elections.

It imposed the veil on female municipal employees; pressured liquor stores, video shops and other un-Islamic establishments to close; and segregated bathing areas by gender.

One demonstration ended in front of the Ministry of Defense where radical leader Ali Benhadj gave an impassioned speech demanding a corp of volunteers be sent to fight for Saddam.

"[58] It soon stepped up its attacks by targeting civilians who refused to live by their prohibitions, and in September 1993 began killing foreigners,[59] declaring that "anyone who exceeds" the GIA deadline of 30 November "will be responsible for his own sudden death.

The violence continued throughout 1994, although the economy began to improve during this time; following negotiations with the IMF, the government succeeded in rescheduling debt repayments, providing it with a substantial financial windfall,[62] and further obtained some 40 billion francs from the international community to back its economic liberalization.

[63] As it became obvious that the fighting would continue for some time, General Liamine Zéroual was named new president of the High Council of State; he was considered to belong to the dialoguiste (pro-negotiation) rather than éradicateur (eradicator) faction of the army.

The largest political parties, especially the FLN and FFS, continued to call for compromise, while other forces—most notably the General Union of Algerian Workers (UGTA), but including smaller leftist and feminist groups such as the secularist RCD—sided with the "eradicators".

[64] In July 1994,[64] the MIA, together with the remainder of the MEI and a variety of smaller groups,[citation needed] united as the Islamic Salvation Army (a term that had previously sometimes been used as a general label for pro-FIS guerrillas), declaring their allegiance to FIS.

But over the months the voluntary "Islamic tax" became a "full-scale extortionist racket, operated by band of armed men claiming to represent an ever more shadowy cause," who also fought each other over turf.

The GIA continued attacks on its usual targets, notably assassinating artists, such as Cheb Hasni, and in late August added a new practice to its activities: threatening insufficiently Islamist schools with arson.

Upon the invitation of the Rome-based Community of Sant'Egidio, in November 1994, they began negotiations in Rome with other opposition parties, both Islamist and secular (FLN, FFS, FIS, MDA, PT, JMC).

Even at this stage, the seemingly counterproductive nature of many of its attacks led to speculation (encouraged by FIS members abroad whose importance was undermined by GIA hostility to negotiation) that the group had been infiltrated by Algerian secret services.

This purge accelerated the disintegration of the GIA: Mustapha Kartali, Ali Benhadjar and Hassan Hattab's factions all refused to recognize Zitouni's leadership starting around late 1995, although they would not formally break away until later.

"Self-defense militias", often called "Patriots" for short, consisting of trusted local citizens trained and armed by the army, were founded in towns near areas where guerrillas were active, and were promoted on national TV.

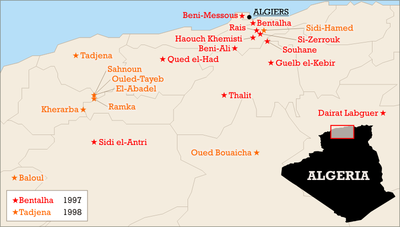

In a communique its amir Antar Zouabri claimed credit for both Rais and Bentalha, calling the killings an "offering to God" and declaring impious the victims and all Algerians who had not joined its ranks.

In some cases, it has been suggested[weasel words] that the GIA were motivated to commit a massacre by a village's joining the Patriot program, which they saw as evidence of disloyalty; in others, that rivalry with other groups (e.g., Mustapha Kartali's breakaway faction) played a part.

[79][80][81] [82][page needed][Note 4] These and other details raised suspicions that the state was in some way collaborating with, or even controlling parts of, the GIA (particularly through infiltration by the secret services) – a theory popularised by Nesroullah Yous, and FIS itself.

[Note 6] In contrast, Algerians such as Zazi Sadou, have collected testimonies by survivors that their attackers were unmasked and were recognised as local radicals – in one case even an elected member of the FIS.

"[89] Another explanation is the "deeply ingrained" tradition of "purposeful accumulation of wealth and status by means of violence",[90] outweighing any basic national identity with feelings of solidarity, loyalty, for what was a province of the Ottoman Empire for much of its history.

Massacres continued throughout 1998 attributed to "armed groups that had formerly belonged to the GIA", some engaged in banditry, other settling scores with the patriots or others, some enlisting in the services of landowners to frighten illegal occupants away.

[citation needed] This law was finally approved by referendum on 16 September 1999, and a number of fighters, including Mustapha Kartali, took advantage of it to give themselves up and resume normal life—sometimes angering those who had suffered at the hands of the guerrillas.

FIS leadership expressed dissatisfaction with the results, feeling that the AIS had stopped fighting without solving any of the issues; but their main voice outside of prison, Abdelkader Hachani, was assassinated on 22 November.

The GIA, torn by splits and desertions and denounced by all sides even in the Islamist movement, was slowly destroyed by army operations over the next few years; by the time Algerian security forces killed Antar Zouabri in Boufarik on 8 February 2002, it was effectively incapacitated.

Its southern division, led by Amari Saifi (nicknamed "Abderrezak el-Para", the "paratrooper"), kidnapped a number of German tourists in 2003, before being forced to flee to sparsely populated areas of Mali, and later Niger and Chad, where he was captured.

[citation needed] Lawyer Ali Merabet, for example, founder of Somoud, an NGO which represents the families of the disappeared, was opposed to the Charter which would "force the victims to grant forgiveness".

[104] At least at first, the "unspeakable atrocities" and enormous loss of life on behalf of a military defeat "drastically weakened Islamism as a whole" throughout the Muslim world, and led to much time and energy being spent by Islamists distancing themselves from extremism.