Ali al-Hadi

[2] In view of their restricted life in the garrison town of Samarra under Abbasid surveillance, Ali and his son Hasan share the title al-Askari (Arabic: عسكري, lit. 'military').

[6] Ali al-Hadi was born on 16 Dhu al-Hijja 212 AH (7 March 828 CE) in Sorayya, a village near Medina founded by his great-grandfather, Musa al-Kazim.

[9] Ali al-Hadi was the son of Muhammad al-Jawad (d. 835), the ninth of the Twelve Imams, and his mother was Samana (or Susan), a freed slave (umm walad) of Maghrebi origin.

Ithbat al-wassiya, a collective biography of the Shia Imams attributed to him,[11] reports that Ali was first taken to Medina sometime after 830, when al-Jawad and his family left Iraq to perform Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca.

Ithbat reports that Umar ibn al-Faraj al-Rukhaji, an Abbasid official known for his hostility to Shias,[24] visited Medina soon after the death of al-Jawad and placed Ali under the care of a non-Shia tutor, named Abu Abd-Allah al-Junaydi.

[26][26] This exceptional innate knowledge of the young Ali is also claimed by the prominent Twelver theologian al-Mufid (d. 1022) in his biographical Kitab al-Irshad, which is considered reliable and unexaggerated by most Shias.

[1][13] He engaged in teaching in Medina after reaching adulthood, possibly attracting a large number of students from Iraq, Persia, and Egypt, where the House of Muhammad traditionally found the most support.

[34] This account is dated 232 AH (846-7) and narrated by a servant in the court of al-Wathiq, named Khayran al-Khadim, whom Ali al-Hadi inquires about the caliph's health.

[45] As the governor of the holy cities in the Hejaz, al-Mutawakkil appointed Umar ibn Faraj, who prevented Alids from answering religious inquiries or accepting gifts, thus pushing them into poverty.

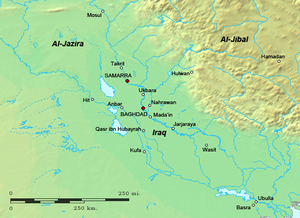

[46] The caliph also created a new army, known as Shakiriyya, which recruited from anti-Alid areas, such as Syria, al-Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia), the Jibal, the Hejaz, and from the Abna, a pro-Abbasid ethnic group.

[7] The caliph responded respectfully but also requested that he with his family relocate to the new Abbasid capital of Samarra,[7] a garrison town where the Turkish guards were stationed, north of Baghdad.

[52] The Muslim academic Jassim M. Hussain suggests that al-Hadi was summoned to Samarra and held there because the investigations of caliph's officials, including Abd Allah, had linked the Shia Imam to the underground activities of the Imamites in Baghdad, al-Mada'in, and Kufa.

[7] His view is that al-Hadi was allowed to move freely within the city, and continued to send (written) instructions for his representatives across the Abbasid empire and receive through them the donations of Shias.

[80][81] Shortly before the overthrow of al-Mutawakkil in 861,[43] a temporary imprisonment of al-Hadi is reported in I'lam by the Twelver historian al-Tabarsi (d. 1153) and in Bihar, under the custody of one Ali ibn Karkar.

[82] Also dated 861, the biographical al-Khara'ij by the Twelver scholar Qutb al-Din al-Rawandi (d. 1178) similarly reports a house arrest of al-Hadi under Sa'id al-Hajib, who was allegedly ordered to kill the Imam.

The offer was taken up by an Indian knowledgeable of various sleights of hand, the report continues, who arranged for the loaves of bread to move away when al-Hadi reached for them, bringing the crowd to laughter.

[87] Ali al-Hadi continued to live in Samarra after the assassination of al-Mutawakkil in 861, through the short reign of al-Muntasir (r. 861–862), followed by four years of al-Musta'in (r. 862–866), and until his death in 868 during the caliphate of al-Mu'tazz (r. 866–869).

Later under al-Mu'tazz, the Abbasids discovered connections between some rebels in Tabaristan and Rayy and certain Imamite figures close to al-Hadi, who were thus arrested in Baghdad and deported to Samarra.

"[17] There is also a tradition attributed to Muhammad al-Baqir (d. 732), the fifth of the Twelve Imams, to the effect that none of them would escape an unjust death after attaining fame, except their last, whose birth would be concealed from the public.

[100][101] After accounting for the bias of his Twelver sources, the historian Dwight M. Donaldson (d. 1976) writes that al-Hadi comes across to him as a "good-tempered, quiet man," who endured for years the "hatred" of al-Mutawakkil with dignity and patience.

[103] In such situations, the response of al-Hadi in Shia sources is often to invoke the intervention of God through prayer,[103] for he viewed the "invocation of oppressed against the oppressor" more powerful than "cavalry, weapons, or spirits,"[104] in a tradition attributed to him in Bihar.

[105] To showcase what she describes as the detachment of al-Hadi from "the trivial anxieties of al-dunya [the material world]," Wardrop mentions the account of an occasion when his house was searched at night for money and weapons,[106] as given by the Twelver sources al-Kafi, al-Irshad, and I'lam.

[106] After this futile search and similar episodes, al-Hadi again invokes the power of God in Shia sources rather than indulging in "verbal attack or enraged silence.

[112] When al-Jawad died, Ahmad met with Muhammad ibn al-Faraj al-Rukhaji and ten other unnamed Imamite figures and listened to Abu al-Khayrani.

[119] More evidence is found in the will attributed to al-Jawad in Kitab al-Kafi, which stipulates that his son Ali would inherit from him and be responsible for his younger brother, Musa, and his sisters.

When asked about it, however, al-Hadi rejected any miraculous interpretation of the incident, saying that he had simply recognized the signs of a brewing storm as a native,[62] as reported in al-Muruj by al-Mas'udi.

[160] Similarly, some followers of Faris ibn Hatim claimed that he was succeeded by his son Muhammad,[136] who appointed his brother Ja'far as the next Imam before his death during the lifetime of al-Hadi.

[138] This was apparently an act of defiance to Hasan al-Askari,[138] who had sided with his father al-Hadi when he excommunicated Faris for embezzling religious funds and openly inciting against him.

[162] One example is the response of al-Hadi to a letter from his new agent Hasan ibn Rashid, in which the former describes Khums as a levy on possessions and produce, and on traders and craftsmen, after they had provided for themselves.

[163] Donaldson quotes one of the prophetic traditions related on the authority of al-Hadi, through Ali ibn Abi Talib, which defines faith (iman) as contained in the hearts of men, confirmed by their deeds (a'mal), whereas surrender (islam) is what the tongue expresses which only validates the union.