Alix Payen

Her letters, a rare contemporary testimony, give an account of women's participation in the fighting and their place in it, ambiguous between overstepping a space reserved for men and accepting male domination, through the duties imposed on the wife who follows her husband.

After his death, his correspondence was published in 1910 by Paul Milliet, Alix Payen's brother, as part of a family biography in the Cahiers de la Quinzaine directed by Charles Péguy, and then in 2020 in a book dedicated to him by Michèle Audin.

This resulted in the fall of the Emperor and the siege of Paris, which began in September 1870 and ended on March 2 of the following year, and which saw the defeat of the nascent French Republic, then led by the monarchists.

[7][19] Paul, who had been active in combat since August in the 1st company of engineers of the Paris army, was successively posted to the Avron plateau, Pantin, Le Bourget in December[19] and Buzenval in January.

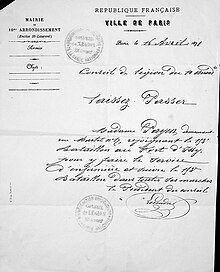

[28] Their correspondence resumed in April, between Paris, where Alix Payen, her husband, her mother, her brother and her sister were based, and the Colonie de Condé-sur-Vesgre where Félix Milliet was once again alone.

If the transport of letters sent from Paris was ensured by Albert Theisz, administrator of the postal services during the insurrectionary period, via Saint-Denis, the reverse correspondence was much more complex.

[...] But you understand that this is not the time to leave Henri there".Fighting broke out near Paris in the first days of April 1871, pitting Commune supporters against Versailles troops, who were responding to the "chief executive" of the new republic, Adolphe Thiers.

[...] Mr S. took me there very reluctantly and often told me that there was still time to change my mind".On the battlefield,[35][37] Alix Payen shares the difficult living conditions of the soldiers.

In the morning, the legion commander Maxime Lisbonne decided to take the battalion to the trenches at Montrouge; the soldiers protested again and managed to settle in the Oiseaux building.

In 1873 she was to marry Édouard Lockroy, a journalist and member of the Radical Party, who was to become a minister, but the project fell through after he was sentenced to prison for his writings in Le Rappel.

[4][56] In order to support herself,[17] Alix Payen tried to reconvert to art,[55] an activity already practised by her brother Paul - who made a career in it - by her father[6] and her younger sister.

In the family biography, her brother Paul Milliet wrote: "Alix Payen, not being married under the community property regime, could have saved her dowry; she abandoned it to her husband's creditors.

[69] Michèle Audin speculates on the invisibility of her existence and that of her writings - even though Édith Thomas had mentioned her in her book Les Pétroleuses - and on the fact that Alix Payen does not correspond to the stereotypes constructed by the Versaillais or those of historians specialising in the Commune.

[73] Four years later, he brought together all of these chapters in a two-volume work, Une famille de républicains fouriéristes, les Milliet,[1] which he had published by Georges Crès.

[3] Even though he reworked some of the letters,[70] he gave them a prominent place in the chapter dedicated to the Commune battles, to the point that they alone constitute the narrative and that Paul Miliet intervenes only to specify the historical context.

After having had access to the family archives of the descendants of Louise Milliet's daughter,[28] held by Danielle Duizabo, she had them published, with many unpublished works,[60] by Libertalia in 2020, under the title C'est la nuit surtout que le combat devient furieux.

[80][9] In this regard, she wrote on 24 April: "When we left Issy [for Vanves], an order had been read to us stating that from now on the advanced posts would be relieved every 24 hours, in spite of this we stayed three days in this cesspool.

[...] The beds are bad and there is a lack of medicine; there is all that is needed for surgery, but no other remedies, so one of our men is devoured by fever and for the last four days the major has not been able to get any quinine".In spite of everything, Alix Payen testifies to the good comradeship within the 153rd Battalion and to the attention she receives from the soldiers.

[87] Chanoine, a worker in Henri Payen's factory[86][Alpha 7] from Clichy,[88] is compared to the figure of the "Parisian from the suburbs, cheerful, mocking, a bit of a rogue".

[88] Alix Payen also writes about Émile Lalande, the commander of the battalion,[41] who "is said to be very energetic and very brave; his physiognomy seems to indicate this",[87] or, on several occasions, about Mme Mallet, a "fancy canteen girl" and a half-caste.

[89][12] Her husband Henry was killed on 27 April in the annex of the Oiseaux convent,[72] so, having returned to Paris on the day of the tragedy, Alix Payen welcomed Mrs. Mallet into her home.

[15] Louise Milliet, her little sister aged seventeen, developed radical and spontaneous ideas,[9] expressed her sympathies towards the Commune and her antipathy towards the Church,[58] whereas her mother was more critical and moderate.

So I look and I listen, the great malaise is that men are lacking, on the one hand there are only the old gossipers of 1830 and on the other, green fruit that is not ripe at all".Their letters, like those of Alix Payen before her departure for combat, also bear witness to life in a Paris that was twice besieged.

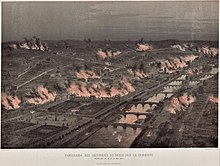

"I hear that the most frightening rumours are being spread in the provinces about Paris, which is nevertheless very quiet and has not yet looted or killed anything, whatever the Versaillais say".Thus, the correspondence within the Milliet family is a source of description of several events of the Commune, or others that just precede it: the uprising of 22 January 1871 and its murderous shootings at the Hôtel de Ville,[28][24] an important funeral procession for national guards killed during the first confrontations - and first defeats - on 9 April from the Palais de l'Industrie,[28] a demonstration of 6,000 Freemasons for conciliation on April 29 - many of whom took up arms alongside the Fédérés[Alpha 8][74] or the fighting and fires during the Semaine sanglante, when Versailles troops took over Paris, which Mother Louise Milliet describes with observation.

[91][9] "Paris was in flames on all sides, we were fighting on the Boulevard Montparnasse and the Observatory when suddenly fire broke out in the Luxembourg barracks and a moment later the powder magazine blew up!

Shrapnel and bullets rained down on us, we were there about forty people, it was impossible to escape, they were fighting on the boulevard, the attack and defence were furious at the Panthéon, the National Guards had received orders to blow up the Panthéon and even, it is said, the St. Etienne library".Among the women who joined the Paris Commune, the majority did so with a political aim, with the desire to build a new society and improve the condition of women.

Her bourgeois origin also distinguishes her from most of the Communard women, who come from the bottom of the wage scale and live a life of misery, toil and struggle to feed their children.

[92][83][9] Dr. Carolyn J. Eichner,[93] in an analysis in her 2004 book Surmounting the Barricades: Women in the Paris Commune, sees her as an illustration of how a woman's social position affects her life on the battlefield.

Alix Payen's companions thus provide her with privileges based on her presumed demands as a bourgeois woman, even though their temporary abandonment does not seem to bother her.

She committed herself more out of love for Henri Payen than out of militancy,[Alpha 9] complying with the duty of a wife imposed on her, even if it meant sacrificing her well-being and putting her life in danger.