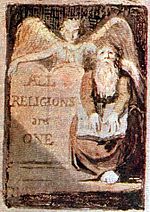

All Religions are One

As such, they serve as a significant milestone in Blake's career; as Peter Ackroyd points out, "his newly invented form now changed the nature of his expression.

[5] All traditional methods of engraving and etching were intaglio, which meant that the design's outline was traced with a needle through an acid-resistant 'ground' which had been poured over the copperplate.

Blake himself referred to relief etching as "printing in the infernal method, by means of corrosives [...] melting apparent surfaces away, and displaying the infinite which was hid.

Blake's new method was autographic; "it permitted – indeed promoted – a seamless relationship between conception and execution rather than the usual divisions between invention and production embedded in eighteenth-century print technology, and its economic and social distinctions among authors, printers, artists and engravers.

The title page from another copy (colour printed in brown ink), the additional plates of which are unrecorded, is in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

In numerous cases, it seems as if the acid has eaten away too much of the relief, and Blake has had to go over sections with ink and wash, often touching the text and design outlines with pen.

The black ink framing lines drawn around each design are thought to have been added at a later date, possibly in 1818, just prior to Blake giving the plates to John Linnell.

It may have subsequently been owned by William Muir but was ultimately sold at Sotheby's by Sir Hickman Bacon on 21 July 1953, to Geoffrey Keynes, who donated it to the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1982.

"[20] In his 1978 book, The Complete Graphic Works of William Blake, David Bindman initially disagreed with Keynes, arguing that the imperfections in All Religions are not because of an earlier date of composition, but because of the increased complexity of the plates, with such complexity demonstrating Blake growing in confidence from the more rudimentary plates for No Natural Religion.

When analysing All Religions are One it is important to remember that the images are not necessarily literal depictions of the text; "the philosophical propositions [...] offer little visual imagery or even named objects.

David Bindman classifies All Religions are One as "a rather abstract dialogue with conventional theology,"[43] and in this sense, it is often interpreted as Blake's earliest engagement with deism and dualism.

"[45] Working along the same lines, Florence Sandler argues that in these texts Blake "set himself to the task of separating true religion from its perversions in his own age and in the Bible itself.

"[46] Also concentrating on the refutation of deism, Alicia Ostriker refers to the series as a "mockery of rationalism and an insistence on Man's potential infinitude.

"[47] S. Foster Damon suggests that what Blake has done in All Religions are One is "dethroned reason from its ancient place as the supreme faculty of man, replacing it with the Imagination.

"[48] Damon also argues that "Blake had completed his revolutionary theory of the nature of Man and proclaimed the unity of all true religions.

"[49] Harold Bloom reaches much the same conclusion, suggesting that Blake is arguing for the "primacy of the poetic imagination over all metaphysical and moral systems.

"[50] A similar conclusion is reached by Denise Vultee, who argues that "the two tractates are part of Blake's lifelong quarrel with the philosophy of Bacon, Newton, and Locke.

Rejecting the rational empiricism of eighteenth-century deism or "natural religion", which looked to the material world for evidence of God's existence, Blake offers as an alternative the imaginative faculty or "Poetic Genius".

"[55] While the Lavater and Swedenborg influences are somewhat speculative, the importance of Bacon, Newton and Locke is not, as it is known that Blake despised empiricism from an early age.

how can I then hear it Contemnd without returning Scorn for ScornHarold Bloom also cites the work of Anthony Collins, Matthew Tindal and John Toland as having an influence on Blake's thoughts.

[56] In a more general sense, "Blake sees the school of Bacon and Locke as the foundation of natural religion, the deistic attempt to prove the existence of God on the basis of sensate experience and its rational investigation.

"[58] Similarly, Eaves, Essick and Viscomi state that they "contain some of Blake's most fundamental principles and reveal the foundation for later development in his thought and art.

"[59] As an example of how Blake returned to the specific themes of All Religions, in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790), he writes "the Poetic Genius was the first principle and all the others merely derivative" (12:22–24).