Allegations of biological warfare in the Korean War

Allegations that the United States military used biological weapons in the Korean War (June 1950 – July 1953) were raised by the governments of the People's Republic of China, the Soviet Union, and North Korea.

Pak cited documents captured from South Korean forces that described plans "for the use of bacteria in diversionary work on the territory of North Korea."

The Soviet Union vetoed the American resolution due to extensive US influence inside the Red Cross, and, along with its allies, continued to insist on the veracity of the biological warfare accusations.

[10][17] Despite the allegations of torture, a United Press report in February 1954 described how U.S. flyers had been instructed by their superior officers that if they were captured on missions they could, according to Marine Major Walter R. Harris, "tell anything you want to."

This commission had several distinguished scientists and doctors from France, Italy, Sweden, Brazil and Soviet Union, including renowned British biochemist and sinologist Joseph Needham.

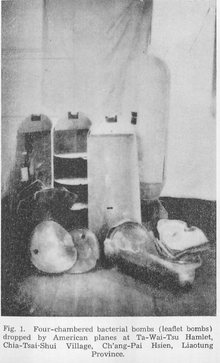

The commission's findings included dozens of eyewitnesses, testimonies from doctors, medical samples from the deceased, bomb casings as well as four American Korean War prisoners who confirmed the US use of biological warfare.

[10] Former members of Unit 731 were linked initially, by a Communist news agency, to a freighter that allegedly carried them and all equipment necessary to mount a biological warfare campaign to Korea in 1951.

[27][10] Citing the claims Ishii had visited South Korea, the report stated: "Whether occupation authorities in Japan had fostered his activities, and whether the American Far Eastern Command was engaged in making use of methods essentially Japanese, were questions which could hardly have been absent from the minds of members of the Commission.

[30] The Communists also alleged that US Brigadier General Crawford Sams had carried out a secret mission behind their lines at Wonsan in March 1951, testing biological weapons.

"[39] American authorities long denied the charges of postwar Japanese-United States cooperation in biological warfare developments, despite later incontrovertible proof that the US pardoned Unit 731 in exchange for their research, according to Sheldon H.

[40][unreliable source] Australian journalist, Denis Warner, suggested that the story was concocted by Wilfred Burchett as part of his alleged role as a KGB agent of influence.

[43] Méray has argued the evidence was the result of an elaborate conspiracy: "Now somehow or other these flies must have been brought there ... the work must have been carried out by a large network covering the whole of North Korea.

[11] After learning of the outbreaks, Mao Zedong immediately requested Soviet assistance on disease preventions, while the Chinese People's Liberation Army General Logistics Department was mobilized for anti-bacteriological warfare.

For example, it has been noted that spring time is usually a period of epidemics within China and North Korea,[45] and years of warfare had also caused a breakdown in the Korean health care system.

[48][49] In 1986, Australian historian Gavan McCormack argued that the claim of US biological warfare use was "far from inherently implausible", pointing out that one of the POWs who confessed, Walker Mahurin, was in fact associated with Fort Detrick.

[50] He also pointed out that, as the deployment of nuclear and chemical weapons was considered, there is no reason to believe that ethical principles would have overruled the resort to biological warfare.

In a book about North Korea, he wrote that the alleged Soviet archival documents published by Kathryn Weathersby and Milton Leitenberg in 1998 (see discussion in section on "Endicott and Hagerman" below) had “provided a fragmentary, but persuasive, explanation of what had actually happened” in relation to the germ warfare charges.

According to McCormack, “Analysis of these documents makes it seem almost certain that there was a vigorous, complex, contrived, and fraudulent international campaign on the part of the North Koreans, the Chinese, and the Russians — a gigantic fraud….”[53] In a 1988 book Korea: The Unknown War, historians Jon Halliday and Bruce Cumings also suggested the claims might be true.

[58] According to Jeffrey Kaye's interpretation of a "Memorandum of Conversation" from the Psychological Strategy Board (PSB) dated 6 July 1953 (and declassified and released by the CIA in 2006),[59] the US protestations at the United Nations did not mean the US was serious about conducting any investigation into biological warfare charges, despite what the government said publicly.

Investigative journalist Simon Winchester concluded in 2008 that Soviet intelligence was sceptical of the allegation, but that North Korean leader Kim Il Sung believed it.

[64] In this program, Professor Mori Masataka investigated historical artifacts in the form of bomb casings from US biological weapons, contemporary documentary evidence and eyewitness testimonies.

The program also uncovered a crucial document in the US National Archives which showed that in September 1951, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff issued orders to start "large scale field tests ... to determine the effectiveness of specific BW [bacteriological warfare] agents under operational conditions".

Its authenticity subsequently has been called into question by the Chinese Memorial of the War to Resist US Aggression and Aid Korea as unverifiable, because every single figure involved in the alleged private conversations and insider events from the account who could testify otherwise, had died before the date of publication.

[69][70] In 1998, Canadian researchers and historians Stephen L. Endicott and Edward Hagerman of York University made the case that the accusations were true in their book, The United States and Biological Warfare: Secrets from the Early Cold War and Korea.

[73] In response, Kathryn Weathersby and Milton Leitenberg of the Cold War International History Project at the Woodrow Wilson Center released a cache of Soviet and Chinese documents in 1998 that they said revealed the allegations to have been an elaborate disinformation campaign.

[75] They said that North Korea's health minister traveled in 1952 to the remote Manchurian city of Mukden where he procured a culture of plague bacilli which was used to infect condemned criminals as part of an elaborate disinformation scheme.

The advisor of the MVD [Ministry of Internal Affairs] DPRK proposed to infect with the cholera and plague bacilli persons sentenced to execution..." These documents revealed that only after Stalin's death the following year did the Soviet Union halt the disinformation campaign.

[77][78][79] In 2001, writer Herbert Romerstein supported Weathersby and Leitenberg's position while criticizing Endicott's research on the basis that it is based on accounts provided by the Chinese government.

They claimed that even if genuine the documents do not prove the United States did not use biological weapons, and they pointed out what they asserted to be various errors and inconsistencies in Weathersby and Leitenberg's analysis.

[81] According to Australian author and judge, Michael Pembroke, the documents associated with Beria (published by Weathersby and Leitenberg) were mostly created during the time of the power struggle after Stalin's death and are therefore questionable.

Chinese and

Soviet forces

• South Korean, U.S.,

Commonwealth

and United Nations

forces