Allegra Byron

Byron placed her with foster families and later in a Roman Catholic convent, where she died at the age of five of typhus or malaria.

Allegra was the product of a short-lived affair between the Romantic poet and her starstruck teenage mother, who was living in reduced circumstances in the household of her stepsister and brother-in-law.

William Godwin, Mary's father and Clairmont's stepfather, had immediately leapt to that conclusion when he learned of Allegra's birth.

[5] After the child's birth, Shelley wrote to Byron "of the exquisite symmetry" and beauty of "a little being whom we ... call Alba, or the Dawn."

Hostile to Clairmont and initially sceptical that he had fathered her daughter, Byron agreed to take custody of Allegra under the condition that her mother have only limited contact with her.

During the journey to turn the child over to Byron, Clairmont wrote in her journal that she had bathed her daughter in Dover, but then crossed the passage out, as if afraid to mention the baby's name.

"[10] In an 1818 letter to his half-sister Augusta Leigh, Byron wrote that "She is very pretty — remarkably intelligent ... She has very blue eyes — that singular forehead — fair curly hair — and a devil of a spirit.

Can't articulate the letter 'r' at all—frowns and pouts quite in our way—blue eyes—light hair growing darker daily—and a dimple in the chin—a scowl on the brow—white skin—sweet voice—and a particular liking of Music—and of her own way in every thing—ah, is that not B. all over?

At the age of four, the naughty child terrorised Byron's servants with her spectacular temper tantrums and other misbehaviour and told frequent lies.

[16] Shelley, who visited the toddler Allegra while she was being boarded with a family chosen by Byron, objected to the child's living arrangements over the years, though he had initially approved of Clairmont's plan to relinquish her to her father.

Clairmont was alarmed by reports in 1820 that her daughter had suffered a malarial-type fever and that Byron had moved her to warm Ravenna at the height of the summer.

[18] However, Byron didn't want to send Allegra back to be raised in the Shelley household, where he was sure she'd grow ill from eating a vegetarian diet and would be taught atheism.

[16] When he saw her again in August 1821 at the Capuchin Convent of Saint Giovanni in Bagnacavallo, a boarding school attended by the daughters of the nobility, he again felt she looked too pale.

During her three-hour visit with Shelley, she showed him the bed where she slept, the chair where she ate dinner, and the little carriage that she and her best friend used during their strolls in the garden.

"[22] Allegra no longer had any real memory of Clairmont, but had grown attached to "her Mammina", Byron's mistress Teresa, Countess Guiccioli, who had mothered her.

[25] Clairmont had always opposed Byron's decision to send Allegra to a convent, and shortly after the move, she wrote him a furious, condemnatory letter accusing him of breaking his promise that their daughter would never be apart from one of her parents.

"[27] In March 1822, she created a plan to kidnap her daughter from the convent and asked Shelley to forge a letter of permission from Byron.

A Roman Catholic girl with a suitable dowry, raised in a convent, would have a decent chance of marrying into high Italian society.

"If Claire thinks that she shall ever interfere with the child's morals or education, she mistakes; she never shall", wrote Byron in a letter to Richard Belgrave Hoppner in September 1820.

[14][19] Byron had written to Clairmont that he paid double fees to the convent school to ensure that Allegra would receive the best possible care from the nuns.

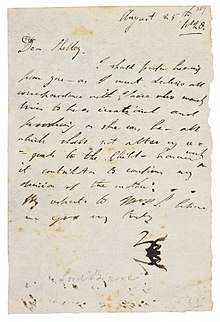

Probably with considerable assistance from the nuns, four-year-old Allegra wrote her father a letter in Italian from the convent, dated 21 September 1821, asking him to visit her: My dear Papa.

[29]The abbess of the convent included her own note inviting Byron to come to see Allegra before he left for Pisa and assuring him "how much she is loved".

[29] On the back of this letter, Byron wrote: "Sincere enough, but not very flattering – for she wants to see me because 'it is the fair' to get some paternal Gingerbread – I suppose."

The same imagination that led us to slight or overlook their sufferings, now that they are forever lost to us, magnifies their estimable qualities ... How did I feel this when my daughter, Allegra, died!