Allied invasion of Italy

[6] Discussions had been ongoing since the Trident Conference held in Washington, D.C., in May, but it was not until late July, with the fall of Italian Fascist Prime Minister Benito Mussolini, that the Joint Chiefs of Staff[7] instructed General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander in the Mediterranean theater, to go ahead.

The overthrow of Mussolini made a more ambitious plan feasible, and the Allies decided to make their invasion two-pronged by combining the crossing of the British Eighth Army under General Sir Bernard Montgomery into the mainland with the simultaneous seizure of the port of Naples further north.

Operation Baytown was the preliminary step in the plan in which the British Eighth Army would depart from the port of Messina, Sicily, across the narrow Straits and land near the tip of Calabria (the "toe" of Italy), on 3 September 1943.

He predicted it would be a waste of effort since it assumed the Germans would give battle in Calabria; if they failed to do so, the diversion would not work, and the only effect of the operation would be to place the Eighth Army 480 km (300 mi) south of the main landing at Salerno.

Six days later it was replaced by Operation Giant, in which two regiments of the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division (Major General Matthew Ridgway) would seize and hold crossings over the Volturno River.

[14] Following the disappointing air cover from land-based aircraft shown during the battle of Gela in the Sicily landings, Force V of HMS Unicorn and four escort carriers augmented the cruisers USS Philadelphia, Savannah, Boise, and fourteen destroyers of Hewitt's command.

[14] In the original planning, the great attraction of capturing the important port of Taranto in the "heel" of Italy had been evident and an assault had been considered but rejected because of the very strong defenses there.

[19] Clark initially provided no troops to cover the river, offering the Germans an easy route to attack, and only belatedly landed two battalions to protect it.

41 (Royal Marine) Commando), was tasked with holding the mountain passes leading to Naples, but no plan existed for linking the Ranger force up with X Corps' follow-up units.

[25] Albert Kesselring and his staff did not believe the Calabria landings would be the main Allied point of attack, the Salerno region or possibly even north of Rome being more logical.

[26] On 4 September, the British 5th Infantry Division reached Bagnara Calabra, linked up with 1st Special Reconnaissance Squadron (which arrived by sea) and drove the 3rd Battalion, 15th Panzergrenadier Regiment from its position.

On 8 September, the 231st Independent Brigade Group, under Brigadier Robert "Roy" Urquhart, was landed by sea at Pizzo Calabro, 24 km (15 mi) behind the Nicotera defenses.

The nature of the countryside in the toe of Italy made it impossible to by-pass obstacles and so the Allies' speed of advance was entirely dependent on the rate at which their engineers could clear obstructions.

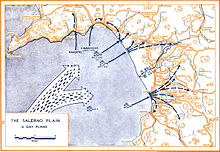

[31] Operation Avalanche–the main invasion at Salerno by the American Fifth Army under Lieutenant General Mark Clark–began on 9 September 1943, and in order to secure surprise, it was decided to assault without preliminary naval or aerial bombardment.

As the first wave of Major General Fred L. Walker's U.S. 36th Infantry Division approached the Paestum shore at 03:30[32] a loudspeaker from the landing area proclaimed in English: "Come on in and give up.

41 (Royal Marine) Commando, were also unopposed and secured the high ground on each side of the road through Molina Pass on the main route from Salerno to Naples.

[38] The 141st Infantry lost cohesion and failed to gain any depth during the day which made the landing of supporting arms and stores impossible, leaving them without artillery and anti-tank guns.

Minesweepers cleared an inshore channel shortly after 09:00; so by late morning destroyers could steam within 90 m (100 yd) of the shoreline to shell German positions on Monte Soprano.

USS Philadelphia and Savannah focused their 15 cm (6 in) guns on concentrations of German tanks, beginning a barrage of naval shells which would total eleven-thousand tons before the Salerno beachhead was secured.

[40] By the end of the first day the Fifth Army, although it had not gained all its objectives, had made a promising start: the British X Corps' two assault divisions had pushed between 8 and 11 km (5 and 7 mi) inland and the special forces had advanced north across the Sorrento Peninsula and were looking down on the Plain of Naples.

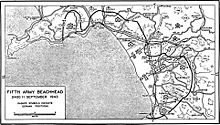

[46] The following morning, Clark moved his headquarters ashore, and Hewitt transferred with his staff to the small amphibious force flagship USS Biscayne so the large Ancon could retire to North Africa.

[55] The battle groups continued their strike south and south-west until reaching the confluence of the Sele and its large tributary the Calore, where it was stopped by artillery firing over open sights, naval gunfire and a makeshift infantry position manned by artillerymen, drivers, cooks and clerks and anyone else that Major General Walker could scrape together.

A clear sign of the crisis passing was when, on the afternoon of 14 September, the final unit of 45th Division, the 180th Infantry Regiment, landed, Clark was able to place it in reserve rather than in the line.

A night drop of 600 paratroops of the 509th Parachute Infantry Battalion to disrupt German movements behind the lines in the vicinity of Avellino was widely dispersed and failed,[60] incurring significant casualties.

With strong naval gunfire support from the Royal Navy and well-served by Fifth Army's artillery, the reinforced and reorganized infantry units defeated all German attempts on 14 September to find a weak spot in the lines.

[66] Montgomery had no choice- while reorganizing the main body of his troops, he sent light forces up the coast which reached Castrovillari and Belvedere on 12 September, still some 130 km (80 mi) from the Salerno battlefield.

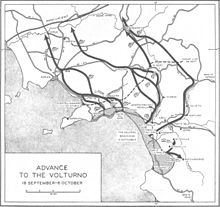

[67] On 16 September, the overall commander of forces in the Salerno area, General von Vietinghoff, reported to Field Marshal Kesselring that the Allied air and naval superiority were decisive and that he didn't have the power to neutralize it.

[68] General Hermann Balck, commanding XIV Panzer Corps - the principal armoured formation near Salerno - wrote that his tanks ‘suffered heavily under Allied naval gunfire, with which [they] had nothing to counter'.

At the same time British X Corps made good progress; they pushed through the mountain passes of Monti Lattari and captured a vital bridge over the Sarno River at Scafati.

On 6 November,[72] Hitler ordered Rommel to withdraw to Northern France and gave Kesselring command of the whole of Italy, instructing him that he keep Rome in German hands for as long as possible.