Dominance hierarchy

Different types of interactions can result in dominance depending on the species, including ritualized displays of aggression or direct physical violence.

[8] In sheep, position in a moving flock is highly correlated with social dominance, but there is no definite study to show consistent voluntary leadership by an individual.

Age, intelligence, experience, and physical fitness can influence whether or not an individual deems it worthwhile to pursue a higher ranking in the hierarchy, which often comes at the expense of conflict.

[13] A 2016 study determined that higher status increased reproductive success amongst men, and that this did not vary by type of subsistence (foraging, horticulture, pastoralism, agriculture).

In red deer, the males who experienced winter dominance, resulting from greater access to preferred foraging sites, had higher ability to get and maintain larger harems during the mating season.

[12] In the monogynous bee species Melipona subnitida, the queen seeks to maintain reproductive success by preventing workers from caring for their cells, pushing or hitting them using her antennae.

[12] In great tits and pied flycatchers, high-ranking individuals experience higher resting metabolic rates and therefore need to consume more food in order to maintain fitness and activity levels than do subordinates in their groups.

The energetic costs of defending territory, mates, and other resources can be very consuming and cause high-ranking individuals, who spend more time in these activities, to lose body mass over long periods of dominance.

In hens, it has been observed that both dominants and subordinates benefit from a stable hierarchical environment, because fewer challenges means more resources can be dedicated to laying eggs.

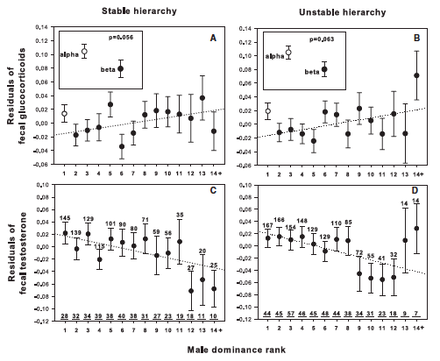

[22] Alpha male savanna baboons have high levels of testosterone and stress; over a long period of time, this can lead to decreased fitness.

[24] Burying beetles, which have a social order involving one dominant male controlling most access to mates, display a behavior known as sneak copulation.

[25] In flat lizards, young males take advantage of their underdeveloped secondary sex characteristics to engage in sneak copulations.

This strategy does not work at close range because the chemical signals given off by the sneaky males reveal their true nature, and they are chased out by the dominant.

Brown hyenas, which display defined linear dominance in both sexes, allow subordinate males and females decreased time of feeding at a carcass.

Among brown hyenas, subordinate females have less opportunity to rear young in the communal den, and thus have fewer surviving offspring than do high-ranking individuals.

In the red fox it has been shown that subordinate individuals, given the opportunity to desert, often do not due to the risk of death and the low possibility that they would establish themselves as dominant members in a new group.

The influence of aggression, threats, and fighting on the strategies of individuals engaged in conflict has proven integral to establishing social hierarchies reflective of dominant-subordinate interactions.

Hence, hierarchy serves as an intrinsic factor for population control, ensuring adequate resources for the dominant individuals and thus preventing widespread starvation.

In eusocial insects, aggressive interactions are common determinants of reproductive status, such as in the bumblebee Bombus bifarius,[36] the paper wasp Polistes annularis[37] and in the ants Dinoponera australis and D.

[41] In the honey bee Apis mellifera, a pheromone produced by the queen mandibular glands is responsible for inhibiting ovary development in the worker caste.

[46] Further, foundresses with larger corpora allata, a region of the female wasp brain responsible for the synthesis and secretion of juvenile hormone, are naturally more dominant.

Former research suggests that primer pheromones secreted by the queen cause direct suppression of these vital reproductive hormones and functions however current evidence suggests that it is not the secretion of pheromones which act to suppress reproductive function but rather the queen's extremely high levels of circulating testosterone, which cause her to exert intense dominance and aggressiveness on the colony and thus "scare" the other mole-rats into submission.

High social rank in a hierarchical group of mice has been associated with increased excitability in the medial prefrontal cortex of pyramidal neurons, the primary excitatory cell type of the brain.

This includes the amygdala through lesion studies in rats and primates which led to disruption in hierarchy, and can affect the individual negatively or positively depending on the subnuclei that is targeted.

[57] Another area that has been associated is the dorsal raphe nucleus, the primary serotonergic nuclei (a neurotransmitter involved with many behaviors including reward and learning).

[67] The concept of dominance, originally called "pecking order", was described in birds by Thorleif Schjelderup-Ebbe in 1921 under the German terms Hackordnung or Hackliste and introduced into English in 1927.

[69] This emphasis on pecking led many subsequent studies on fowl behaviour to use it as a primary observation; however, it has been noted that roosters tend to leap and use their claws in conflicts.

The brood hierarchy makes it easier for the subordinate chick to die quietly in times of food scarcity, which provides an efficient system for booby parents to maximize their investment.

This advantage is critical in some ecological contexts, such as in situations where nesting sites are limited or dispersal of individuals is risky due to high rates of predation.

In European badgers, dominance relationships may vary with time as individuals age, gain or lose social status, or change their reproductive condition.