Alphonse Juin

Juin was wounded in his left hand the following day, but refused evacuation to hospital, remaining at the front with his arm in a sling.

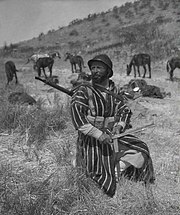

Promoted to capitaine, Juin joined Moroccan troops preparing to go to France, but he accepted an offer from Général de division Hubert Lyautey, the Resident-General in Morocco, to become his aide-de-camp for six months.

Juin returned to France towards the end of 1916 in command of a company of the 1er Régiment de Tirailleurs Marocains [fr], participating in the Nivelle Offensive in April 1917.

When he returned in October 1918, he was initially posted to the staff of his division, but then joined the French Mission to the United States Army, where he served when the fighting ended in November 1918.

For his services leading troops in the field, Juin was made an officer of the Legion of Honour and promoted to Chef de bataillon.

The 15e DIM came under heavy German attack on 24 May, and retreated into the Lille pocket, where it covered the British and French forces fighting in the Battle of Dunkirk.

He was released in June 1941 at the request of Pétain, now the head of the Vichy Government, in exchange for thirty German sailors, as a specialist in North African affairs.

On 20 November, he was promoted to Général de corps d'armée, replacing Maxime Weygand as commander of French land forces in North Africa.

In December he led a French mission to Germany that met with Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring to discuss what would happen if the German-Italian Panzerarmee Afrika was driven out of Libya by Operation Crusader.

This did not occur, but a dispute over what should be done led to Juin relieving de Lattre of command of the forces in Tunisia, permanently damaging their friendship.

[24] He was informed of the landings by Robert Daniel Murphy, the American consul-general in Algiers, on the morning of 8 November 1942 as the first waves were heading toward the beaches.

[28] His command, known as the Détachement d'armée Français, held two distinct sectors on the Tunisian front, one in the north under Général de brigade Fernand Barré, and one in the south under Koeltz.

In January 1943, Juin agreed to a more regular command arrangement, with French forces being concentrated in Koeltz's XIX Corps, which was placed under Lieutenant General Kenneth Anderson's British First Army.

When Juin was informed that Pétain had stripped him of his French nationality and membership in the legion of honour, he merely noted that he was grateful he had not been sentenced to death.

[31] In July 1943, Eisenhower, now the Supreme Allied Commander in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations (MTO), raised the possibility of French troops being used in the upcoming Italian campaign with Juin, who accepted on behalf of Giraud, who was in Washington, D.C.[34] Juin was placed in charge of a force known as Détachement d'armée A, which was intended to eventually grow into an army headquarters.

[38] On 29 January, he reported to Clark that "At the cost of unbelievable efforts and great losses," the 3rd Algerian Infantry Division had "accomplished the mission which you gave them.

The French surprised the enemy and quickly seized key terrain including Mounts Faito Cerasola and high ground near Castelforte.

D'Oro, Ausonia and Esperia were seized in one of the most brilliant and daring advances of the war in Italy, and by May 16 the French Expeditionary Corps had thrust forward some ten miles on their left flank to Mount Revole, with the remainder of their front slanting back somewhat to keep contact with the British Eighth Army.

The French displayed that ability during their sensational advance which Lieutenant General Siegfried Westphal, the chief of staff to Kesselring, later described as a major surprise both in timing and in aggressiveness.

On 4 July, the CEF captured Siena, where it celebrated Bastille Day, and then was withdrawn to participate in Operation Dragoon, codename for the Allied invasion of Southern France.

In the wake of allegations of raping and pillaging by his North African troops in the Marocchinate, he took steps to curtail the abuses,[44] with drastic measures, including the death penalty, that were not entirely successful owing to the animosity between the French and Italian people over the events of 1940.

[45] Following this assignment Juin was appointed chief of staff of French forces ("Chef d'État-Major de la Défense Nationale").

He helped persuade Eisenhower to allow Philippe Leclerc's 2nd Armoured Division to carry out the liberation of Paris, and he entered the city with de Gaulle on 25 August 1944.

He restored order to the liberated areas, suppressing elements of the French Forces of the Interior (FFI) that refused to disband with Spahis that he brought in from North Africa.

He arranged with Eisenhower for FFI personnel to be absorbed into four new divisions that guarded the German forces that remained in bypassed garrisons along the Atlantic coast, and the frontier with Italy.

[46] During the German Operation Northwind in January 1945, he clashed with Eisenhower's chief of staff, Lieutenant General Walter B. Smith, over a proposed Allied withdrawal from Alsace and Lorraine.

Juin lost his direct access to the President when de Gaulle left office in 1946, and his plans for an Army large enough to handle France's commitments had to be scaled back.

[48] He opposed Moroccan attempts to gain independence and worked uneasily with Mohammed V, the Sultan of Morocco, whom Juin correctly suspected of harbouring nationalist sympathies.

[50][51] During his tenure Juin instituted many administrative reforms, and greatly expanded opportunities for Moroccans, but it was overshadowed by the growing drift to independence.

On 17 September, separated from his battalion by the emptiness caused by a deadly attack, remained in his position despite heavy losses suffered by his troop.