Alpine chough

Its two subspecies breed in high mountains from Spain eastwards through southern Europe and North Africa to Central Asia and Nepal, and it may nest at a higher altitude than any other bird.

It feeds, usually in flocks, on short grazed grassland, taking mainly invertebrate prey in summer and fruit in winter; it will readily approach tourist sites to find supplementary food.

Although it is subject to predation and parasitism, and changes in agricultural practices have caused local population declines, this widespread and abundant species is not threatened globally.

Moravian palaeontologist Ferdinand Stoliczka separated the Himalayan population as a third subspecies, P. g. forsythi,[14] but this has not been widely accepted and is usually treated as synonymous with digitatus.

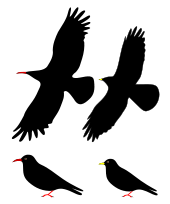

[20] The adult of the nominate subspecies of the Alpine chough has glossy black plumage, a short yellow bill, dark brown irises, and red legs.

[23] The Alpine chough breeds in mountains from Spain eastwards through southern Europe and the Alps across Central Asia and the Himalayas to western China.

It is a non-migratory resident throughout its range, although Moroccan birds have established a small colony near Málaga in southern Spain, and wanderers have reached Czechoslovakia, Gibraltar, Hungary and Cyprus.

[4] The bulky nests are composed of roots, sticks and plant stems lined with grass, fine twiglets or hair, and may be constructed on ledges, in a cave or similar fissure in a cliff face, or in an abandoned building.

The clutch is 3–5 glossy whitish eggs, averaging 33.9 by 24.9 millimetres (1.33 in × 0.98 in) in size,[29] which are tinged with buff, cream or light-green and marked with small brown blotches;[4] they are incubated by the female for 14–21 days before hatching.

[4] Breeding is possible in the high mountains because chough eggs have fewer pores than those of lowland species, reducing loss of water by evaporation at the low atmospheric pressure.

[28] In the summer, the Alpine chough feeds mainly on invertebrates collected from pasture, such as beetles (Selatosomus aeneus and Otiorhynchus morio have been recorded from pellets), snails, grasshoppers, caterpillars and fly larvae.

[5] The diet in autumn, winter and early spring becomes mainly fruit, including berries such as the European Hackberry (Celtis australis) and Sea-buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides),[5] rose hips, and domesticated crops such as apples, grapes and pears where available.

[35] The chough will readily supplement its winter diet with food provided by tourist activities in mountain regions, including ski resorts, refuse dumps and picnic areas.

[34] Movement to lower levels begins after the first snowfalls, and feeding by day is mainly in or near valley bottoms when the snow cover deepens, although the birds return to the mountains to roost.

In March and April the choughs frequent villages at valley tops or forage in snow-free patches prior to their return to the high meadows.

[38] Predators of the choughs include the peregrine falcon, golden eagle and Eurasian eagle-owl, while the common raven will take nestlings.

It seems likely that this "mobbing" behaviour may be play activity to give practice for when genuine defensive measures may be needed to protect eggs or young.

The decline was thought to be due to the loss of former open grasslands which had reverted to scrubby vegetation once extensive cattle grazing ceased.

[52] Choughs can be locally threatened by the accumulation of pesticides and heavy metals in the mountain soils, heavy rain, shooting and other human disturbances,[50] but a longer-term threat comes from global warming, which would cause the species' preferred Alpine climate zone to shift to higher, more restricted areas, or locally to disappear entirely.