Effects of high altitude on humans

After the human body reaches around 2,100 metres (6,900 ft) above sea level, the saturation of oxyhemoglobin begins to decrease rapidly.

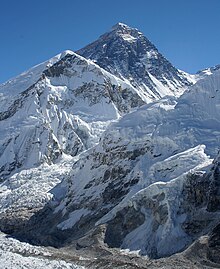

There is a limit to the level of adaptation; mountaineers refer to the altitudes above 8,000 metres (26,000 ft) as the death zone, where it is generally believed that no human body can acclimatize.

The physiological responses to high altitude include hyperventilation, polycythemia, increased capillary density in muscle and hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction–increased intracellular oxidative enzymes.

[10] The International Society for Mountain Medicine recognizes three altitude regions which reflect the lowered amount of oxygen in the atmosphere:[11] Travel to each of these altitude regions can lead to medical problems, from the mild symptoms of acute mountain sickness to the potentially fatal high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) and high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE).

[14] People who develop acute mountain sickness can sometimes be identified before the onset of symptoms by changes in fluid balance hormones regulating salt and water metabolism.

People who are predisposed to develop high-altitude pulmonary edema may present a reduction in urine production before respiratory symptoms become apparent.

[16] At altitudes above 7,500 m (24,600 ft, 383 millibars of atmospheric pressure), sleeping becomes very difficult, digesting food is near-impossible, and the risk of HAPE or HACE increases greatly.

[19] It refers to altitudes above a certain point where the amount of oxygen is insufficient to sustain human life for an extended time span.

[3][4][5] At an altitude of 19,000 m (63,000 ft), the atmospheric pressure is sufficiently low that water boils at the normal temperature of the human body.

[21] Even below the Armstrong limit, an abrupt decrease in atmospheric pressure can cause venous gas bubbles and decompression sickness.

At high altitude, in the short term, the lack of oxygen is sensed by the carotid bodies, which causes an increase in the breathing depth and rate (hyperpnea).

Inability to increase the breathing rate can be caused by inadequate carotid body response or pulmonary or renal disease.

Full hematological adaptation to high altitude is achieved when the increase of red blood cells reaches a plateau and stops.

[6][16] Even when acclimatized, prolonged exposure to high altitude can interfere with pregnancy and cause intrauterine growth restriction or pre-eclampsia.

[28] High altitude causes decreased blood flow to the placenta, even in acclimatized women, which interferes with fetal growth.

These humans have undergone extensive physiological and genetic changes, particularly in the regulatory systems of oxygen respiration and blood circulation, when compared to the general lowland population.

[32][33] Compared with acclimatized newcomers, native Andean and Himalayan populations have better oxygenation at birth, enlarged lung volumes throughout life, and a higher capacity for exercise.

[52] Symptoms of sunburn include red or reddish skin that is hot to the touch or painful, general fatigue, and mild dizziness.

[53] For endurance events (races of 800 metres or more), the predominant effect is the reduction in oxygen, which generally reduces the athlete's performance at high altitude.

The advantage of its high altitude in sprinting and jumping events held out hope of world records, with sponsor Ferrari offering a car as a bonus.

A series of studies conducted in Utah in the late 1990s showed significant performance gains in athletes who followed such a protocol for several weeks.

[64][65] In 2007, FIFA issued a short-lived moratorium on international football matches held at more than 2,500 metres above sea level, effectively barring select stadiums in Bolivia, Colombia, and Ecuador from hosting World Cup qualifiers, including their capital cities.

[66] In their ruling, FIFA's executive committee specifically cited what they believed to be an unfair advantage possessed by home teams acclimated to the elevation.