Amanita bisporigera

The delicate ring on the upper part of the stipe is a remnant of the partial veil that extends from the cap margin to the stalk and covers the gills during development.

When young, the mushrooms are enveloped in a membrane called the universal veil, which stretches from the top of the cap to the bottom of the stipe, imparting an oval, egg-like appearance.

[6] The cap flesh turns yellow when a solution of potassium hydroxide (KOH, 5–10%) is applied (a common chemical test used in mushroom identification).

[6] Findings from the Chiricahua Mountains of Arizona and in central Mexico, although "nearly identical" to A. bisporigera, do not stain yellow with KOH; their taxonomic status has not been investigated in detail.

[6] The volva is composed almost exclusively of densely interwoven filamentous hyphae, 2–10 μm in diameter, that are sparsely to moderately branched.

The tissue of the stipe is made of abundant, sparsely branched, filamentous hyphae, without clamps, measuring 2–5 μm in diameter.

[4] In 1906 Charles E. Lewis studied and illustrated the development of the basidia in order to compare the nuclear behavior of the two-spored with that of the four-spored forms.

Initially (1), the young basidium, appearing as a club-shaped branch from the subhymenium, is filled with cytoplasm and contains two primary nuclei, which have distinct nucleoli.

[8] The Amanita Genome Project was begun in Jonathan Walton's lab at Michigan State University in 2004 as part of their ongoing studies of A. bisporigera.

[9] The purpose of the project is to determine the genes and genetic controls associated with the formation of mycorrhizae, and to elucidate the biochemical mechanisms of toxin production.

[14] Sequence information has also been employed to show that A. bisporigera lacks many of the major classes of secreted enzymes that break down the complex polysaccharides of plant cell walls, like cellulose.

In contrast, saprobic fungi like Coprinopsis cinerea and Galerina marginata, which break down organic matter to obtain nutrients, have a more complete complement of cell wall-degrading enzymes.

[16] A. elliptosperma is less common but widely distributed in the southeastern United States, while A. ocreata is found on the West Coast and in the Southwest.

Other similar toxic North American species include Amanita magnivelaris, which has a cream-colored, rather thick, felted-submembranous, skirt-like ring,[17] and A. virosiformis, which has elongated spores that are 3.9–4.7 by 11.7–13.4 μm.

[24] In 2006, seven members of the Hmong community living in Minnesota were poisoned with A. bisporigera because they had confused it with edible paddy straw mushrooms (Volvariella volvacea) that grow in Southeast Asia.

striatula, a poorly known taxon originally described from the United States in 1902 by Charles Horton Peck,[31] is considered by Amanita authority Rodham Tulloss to be synonymous with A. bisporigera.

This classification has been upheld with phylogenetic analyses, which demonstrate that the toxin-producing members of section Phalloideae form a clade—that is, they derive from a common ancestor.

[32][33] In 2005, Zhang and colleagues performed a phylogenetic analysis based on the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences of several white-bodied toxic Amanita species, most of which are found in Asia.

[34] Fruit bodies of Amanita bisporigera are found on the ground growing either solitarily, scattered, or in groups in mixed coniferous and deciduous forests;[5] they tend to appear during summer and early fall.

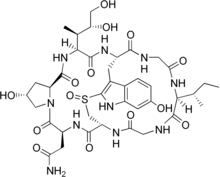

[6] A. bisporigera is considered the most toxic North American Amanita mushroom, with little variation in toxin content between different fruit bodies.

[39][40] Roughly 0.2 to 0.4 milligrams of α-amanitin is present in 1 gram of A. bisporigera; the lethal dose in humans is less than 0.1 mg/kg body weight.

[12] Poisonings (from similar white amanitas) have also been reported in domestic animals, including dogs, cats, and cows.

[42] The first reported poisonings resulting in death from the consumption of A. bisporigera were from near San Antonio, Mexico, in 1957, where a rancher, his wife, and three children consumed the fungus; only the man survived.

In the cytotoxic stage, 24 to 48 hours after ingestion, clinical and biochemical signs of liver damage are observed, but the patient is typically free of gastrointestinal symptoms.