Amaravati Stupa

Amarāvati Stupa is a ruined Buddhist stūpa at the village of Amaravathi, Guntur district, Andhra Pradesh, India, probably built in phases between the third century BCE and about 250 CE.

[4] Largely because of the maritime trading links of the East Indian coast, the Amaravati school or Andhra style of sculpture, seen in a number of sites in the region, had great influence on art in South India, Sri Lanka and South-East Asia.

[5] Like other major early Indian stupas, but to an unusual extent, the Amaravarti sculptures include several representations of the stupa itself, which although they differ, partly reflecting the different stages of building, give a good idea of its original appearance, when it was for some time "the greatest monument in Buddhist Asia",[6] and "the jewel in the crown of early Indian art".

[7] The name Amaravathi is relatively modern, having been applied to the town and site after the Amareśvara Liṅgasvāmin temple was built in the eighteenth century.

The oldest maps and plans, drawn by Colin Mackenzie and dated 1816, label the stūpa simply as the deepaladimma or 'hill of lights'.

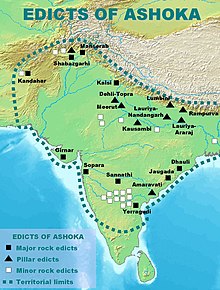

[10] The stupa, or mahāchetiya, was possibly founded in the third century BCE in the time of Asoka but there is no decisive evidence for the date of foundation.

In the early period (circa 200–100 BCE), the stūpa had a simple railing consisting of granite pillars, with plain cross-bars, and coping stones.

James Burgess in his book of 1887 on the site, noted that:[16]wherever one digs at the back of the outer rail, broken slabs, statues &etc, are found jammed in behind it.

Some other types of sculpture belong to an even later time, about the seventh or eighth centuries, and include standing Bodhisattvas and goddesses.

The Chinese traveller and Buddhist monk Hiuen Tsang (Xuanzang) visited Amaravati in 640 CE, stayed for some time and studied the Abhidhammapitakam.

[26] On the right bank of the Krishna River[27] in the Andhra district of southeast India, Mackenzie came across a huge Buddhist construction built of bricks and faced with slabs of limestone.

The curator Dr Edward Balfour was concerned that the artefacts were deteriorating so in 1853 he started to raise a case for them to be moved.

Both uprights and cross-bars were decorated with round medallion or tondo reliefs, the latter slightly larger, and containing the most impressive surviving sculpture.

Very little of the sculpture was found and properly recorded in its original exact location, but the broad arrangement of the different types of pieces is generally agreed.

Fragments have been found of limestone coping stones, some with reliefs of running youths and animals, similar in style to those at Bharhut, so perhaps from c. 150–100 BCE.

[41] The later ones, in limestone, are carved with round lotus medallions, and sometimes panels with figurative reliefs, these mostly on the sides facing in towards the stupa.

Based on the style of the sculpture the construction of the later railing is usually divided into three phases, growing somewhat in size and the complexity of the images.

Only a few fragments from the garland decorations shown high on the dome in drum-slab stupa depictions (one in Chennai is illustrated).

One reason for the use of the terms Amaravati School or style is that the actual find-spot of many Andhran pieces is uncertain or unknown.

The superlative beauty of the individual bodies and the variety of poses, many realizing new possibilities of depicting the human form, as well as the swirling rhythms of the massed compositions, all combine to produce some of the most glorious reliefs in world art".

[50] Unlike other major sites, minor differences in the depiction of narratives show that the exact textual sources used remain unclear, and have probably not survived.

[51] Especially in the later period at Amaravati itself, the main relief scenes are "a sort of 'court art'", showing a great interest in scenes of court life "reflecting the luxurious life of the upper class, rich, and engaged in the vibrant trade with many parts of India and the wider world, including Rome".

[52] Free-standing statues are mostly of the standing Buddha, wearing a monastic robe "organized in an ordered rhythm of lines undulating obliquely across the body and imparting a feeling of movement as well as reinforcing the swelling expansiveness of the form beneath".

There is a "peculiarly characteristic" large fold at the bottom of the robe, one of a number of features similar to the Kushan art of the north.

[53] From the 19th century, it was always thought that the stupa was built under the Satavahana dynasty, rulers of the Deccan whose territories eventually straddled both east and west coasts.

[60] At the later end of the chronology, the local Andhra Ikshvaku ruled after the Satavahanas and before the Gupta Empire, in the 3rd and early 4th centuries, perhaps starting 325–340.

The pictures were made in 1816 and 1817 by a team of military surveyors and draftsmen under the direction of Colonel Colin Mackenzie (1757–1821), the first Surveyor-General of India.