Continental Army

Previously, each colony had relied upon the militia (which was made up of part-time citizen-soldiers) for local defense; or the raising of temporary provincial troops during such crises as the French and Indian War of 1754–1763.

As tensions with Great Britain increased in the years leading to the war, colonists began to reform their militias in preparation for the perceived potential conflict.

Colonists such as Richard Henry Lee proposed forming a national militia force, but the First Continental Congress rejected the idea.

It also raised the first ten companies of Continental troops on a one-year enlistment, riflemen from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia to be used as light infantry.

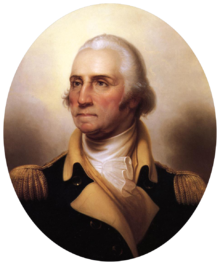

On June 15, 1775, Congress elected by unanimous vote George Washington as Commander-in-Chief, who accepted and served throughout the war without any compensation except for reimbursement of expenses.

[5] On June 15, 1775, Congress elected by unanimous vote George Washington as Commander-in-Chief, who accepted and served throughout the war without any compensation except for reimbursement of expenses.

Horatio Gates held the position (1775–1776), Joseph Reed (1776–1777), George Weedon and Isaac Budd Dunn (1777), Morgan Connor 1777, Timothy Pickering (1777–1778), Alexander Scammell (1778–1781), and Edward Hand (1781–1783).

[7] The Judge Advocate General assisted the commander-in-chief with the administration of military justice, but he did not, as his modern counterpart, give legal advise.

[9] Keeping the continentals clothed was a difficult task and to do this Washington appointed James Mease, a merchant from Philadelphia, as Clothier General.

[25] In 1781 and 1782, Patriot officials and officers in the Southern Colonies repeatedly implemented policies that offered slaves as rewards for recruiters who managed to enlist a certain number of volunteers in the Continental Army; in January 1781, Virginia's General Assembly passed a measure which announced that voluntary enlistees in the Virginia Line's regiments would be given a "healthy sound negro" as a reward.

[25] The officers of both the Continental Army and the state militias were typically yeoman farmers with a sense of honor and status and an ideological commitment to oppose the policies of the British Crown.

[28][29] Up to a fourth of Washington's army were of Scots-Irish (English and Scottish descent) Ulster origin, many being recent arrivals and in need of work.

During the Revolution, African American slaves were promised freedom in exchange for military service by both the Continental and British armies.

[31][32][33] Approximately 6,600 people of color (including African American, indigenous, and multiracial men) served with the colonial forces, and made up one-fifth of the Northern Continental Army.

[34][35] In addition to the Continental Army regulars, state militia units were assigned for short-term service and fought in campaigns throughout the war.

The militia troops developed a reputation for being prone to premature retreats, a fact that General Daniel Morgan integrated into his strategy at the Battle of Cowpens and used to fool the British in 1781.

This led to the army offering low pay, often rotten food, hard work, cold, heat, poor clothing and shelter, harsh discipline, and a high chance of becoming a casualty.

Washington selected young Henry Knox, a self-educated strategist, to take charge of the artillery from an abandoned British fort in upstate New York, and dragged across the snow to and placed them in the hills surrounding Boston in March 1776.

General Washington and other distinguished officers were instrumental leaders in preserving unity, learning and adapting, and ensuring discipline throughout the eight years of war.

Washington always viewed the Army as a temporary measure and strove to maintain civilian control of the military, as did the Continental Congress, though there were minor disagreements about how this was to be carried out.

Throughout its existence, the Army was troubled by poor logistics, inadequate training, short-term enlistments, interstate rivalries, and Congress's inability to compel the states to provide food, money, or supplies.

A small residual force remained at West Point and some frontier outposts until Congress created the United States Army by their resolution of June 3, 1784.

Although Congress declined on May 12 to make a decision on the peace establishment, it did address the need for some troops to remain on duty until the British evacuated New York City and several frontier posts.

When Steuben's effort in July to negotiate a transfer of frontier forts with Major General Frederick Haldimand collapsed, however, the British maintained control over them, as they would into the 1790s.

That failure and the realization that most of the remaining infantrymen's enlistments were due to expire by June 1784 led Washington to order Knox, his choice as the commander of the peacetime army, to discharge all but 500 infantry and 100 artillerymen before winter set in.

On November 2, Washington, then at Rockingham near Rocky Hill, New Jersey, released his Farewell Orders issued to the Armies of the United States of America to the Philadelphia newspapers for nationwide distribution to the furloughed men.

In the message, he thanked the officers and men for their assistance and reminded them that "the singular interpositions of Providence in our feeble condition were such, as could scarcely escape the attention of the most unobserving; while the unparalleled perseverance of the Armies of the United States, through almost every possible suffering and discouragement for the space of eight long years, was little short of a standing Miracle.

"[60] Washington believed that the blending of persons from every colony into "one patriotic band of Brothers" had been a major accomplishment, and he urged the veterans to continue this devotion in civilian life.

Congress ended the War of American Independence on January 14, 1784, by ratifying the definitive peace treaty that had been signed in Paris on September 3.

[61] During the American Revolutionary War, the Continental Army initially wore ribbons, cockades, and epaulettes of various colors as an ad hoc form of rank insignia, as General George Washington wrote in 1775: "As the Continental Army has unfortunately no uniforms in 1775, and consequently many inconveniences must arise from not being able to distinguish the commissioned officers from the privates, it is desired that some badge of distinction be immediately provided; for instance that the field officers may have red or pink colored cockades in their hats, the captains yellow or buff, and the subalterns green.