American Equal Rights Association

In New York, which was in the process of revising its state constitution, AERA workers collected petitions in support of women's suffrage and the removal of property requirements that discriminated specifically against black voters.

The AERA continued to hold annual meetings after the failure of the Kansas campaign, but growing differences made it difficult for its members to work together.

[13] The movement largely disappeared from public notice during the Civil War (1861–1865) as women's rights activists focused their energy on the campaign against slavery.

[14][15] After slavery in the U.S. was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, Wendell Phillips was elected president of the Anti-Slavery Society and began to direct its resources toward winning political rights for blacks.

"[17] Stanton, Anthony and Lucy Stone, the most prominent figures in the women's movement, circulated a letter in late 1865 calling for petitions against any wording that excluded females.

[21] Phillips and other abolitionist leaders expected a constitutional provision of voting rights for former slaves to help preserve the North's recent victory over the slaveholding states during the Civil War.

[23]) Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony issued the call for the Eleventh National Women's Rights Convention, the first since the Civil War began, which met on May 10, 1866, in New York City.

"[28] Asked by George T. Downing, an African American, whether she would be willing for the black man to have the vote before woman, Elizabeth Cady Stanton replied, "I would say, no; I would not trust him with all my rights; degraded, oppressed himself, he would be more despotic with the governing power than even our Saxon rulers are.

AERA workers prepared for it by organizing meetings in over 30 locations around the state and collecting over 20,000 signatures on petitions that supported women's suffrage and the removal of property requirements that discriminated specifically against black voters.

[33] Greeley had earlier clashed with Anthony and Stanton by insisting that their New York campaign should focus on the rights of African Americans rather than also including women's issues.

[36] The History of Woman Suffrage, whose authors include Stanton and Anthony, said, "This campaign cost us the friendship of Horace Greeley and the support of the New York Tribune, heretofore our most powerful and faithful allies.

[38][39] The New York campaign had been financed partly by the Hovey Fund, which was created by a bequest that provided a large sum of money to support abolitionism, women's rights and other reform movements.

They created a storm of controversy by accepting help during the last two and a half weeks of the campaign from George Francis Train, a Democrat, a wealthy businessman and a flamboyant speaker who supported women's rights.

[49] Train was a political maverick who had attended the Democratic convention during the presidential election year of 1864 but then campaigned vigorously for the Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln.

Henry Blackwell, Stone's husband, had just demonstrated that even AERA workers were not automatically free from the racial presumptions of that era by publishing an open letter to Southern legislatures assuring them that if they allowed both blacks and women to vote, "the political supremacy of your white race will remain unchanged"[57] and that "the black race would gravitate by the law of nature toward the tropics.

"[58] Opposition to Train was partly due to the loyalty many reformers felt to the national Republican Party, which had provided political leadership for the elimination of slavery and was still in the difficult process of consolidating that victory.

"[63] After the Kansas campaign ended in disarray in November 1867, the AERA increasingly divided into two wings, both advocating universal suffrage but with different approaches.

One wing, whose leading figure was Lucy Stone, was willing for black men to achieve suffrage first and wanted to maintain close ties with the Republican Party and the abolitionist movement.

[64] Stanton and Anthony expressed their views in a newspaper called The Revolution, which began publishing in January 1868 with initial funding from the controversial George Francis Train.

[73] She believed that a long process of education would be needed before what she called the "lower orders" of former slaves and immigrant workers would be able to participate meaningfully as voters.

"[74] After first saying in another article, "There is only one safe, sure way to build a government, and that is on the equality of all its citizens, male and female, black and white",[75] Stanton then objected to laws being made for women by "Patrick and Sambo and Hans and Yung Tung who do not know the difference between a Monarchy and a Republic".

They wrote a letter to the 1868 Democratic National Convention that criticized Republican sponsorship of the Fourteenth Amendment (which granted citizenship to black men but introduced the word "male" into the Constitution), saying, "While the dominant party has with one hand lifted up two million black men and crowned them with the honor and dignity of citizenship, with the other it has dethroned fifteen million white women—their own mothers and sisters, their own wives and daughters—and cast them under the heel of the lowest orders of manhood.

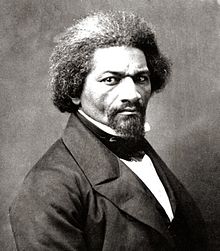

[82] Some, including Lucretia Mott, president of the organization, and African Americans Frederick Douglass and Frances Harper, voiced their disagreements with Stanton and Anthony but continued to maintain working relationships with them.

[92] Distressed at Stanton's and Anthony's association with George Francis Train and the hostilities it had generated, Lucretia Mott resigned as president of the AERA that same month.

"[97] Anthony replied, "Mr. Douglass talks about the wrongs of the negro; but with all the outrages that he to-day suffers, he would not exchange his sex and take the place of Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Two days after the meeting, Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton led the formation of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA).

Theodore Tilton, an abolitionist and women’s rights advocate, organized a petition drive that gathered the names of more than a thousand people who wanted reunification.

Twenty leaders of the AERA, including Stanton, Anthony, Tilton and Stone, met in executive committee on May 14, 1870, to formally end its existence.

[110] Stanton and Anthony, the leading figures in the NWSA, were more widely known as leaders of the women's suffrage movement during this period and were more influential in setting its direction.

"[113] In 1890 the NWSA and the AWSA combined to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), with Stanton, Anthony and Stone as its top officers.