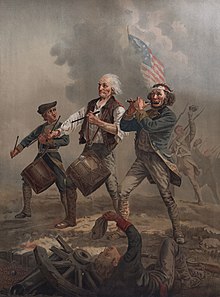

Patriot (American Revolution)

Though slavery existed in all of the Thirteen Colonies prior to the American Revolution, the issue divided patriots, with some supporting its abolition while others espoused proslavery thought.

[1] Prior to the American Revolution, colonists who supported British authority called themselves Tories or royalists, identifying with the political philosophy of traditionalist conservatism as it existed in Great Britain.

The most prominent patriot leaders are referred to today as the Founding Fathers, who are generally defined as the 56 men who, as delegates to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia, signed the Declaration of Independence.

[4] Yale historian Leonard Woods Labaree used the published and unpublished writings and letters of leading men on each side, searching for how personality shaped their choice.

Men who were alienated by physical attacks on Royal officials took the Loyalist position, while those who were offended by British responses to actions such as the Boston Tea Party became patriots.

Merchants in the port cities with long-standing financial attachments to Britain were likely to remain loyal, while few patriots were so deeply enmeshed in the system.

Loyalists were cautious and afraid of anarchy or tyranny that might come from mob rule; patriots made a systematic effort to take a stand against the British government.