American entry into World War I

While the country was at peace, American banks made huge loans to the Entente powers (Allies), which were used mainly to buy munitions, raw materials, and food from across the Atlantic in North America from the United States and Canada.

The aim was to break the trans-atlantic supply chain to Britain from other nations to the West, although the German high command realized that sinking American-flagged ships would almost certainly bring the United States into the war.

Nevertheless, without consulting colleagues earlier superiors like Tirpitz, the outgoing head of the German Admiralty Hugo von Pohl (1855–1916), declared the beginning of the first round of unrestricted submarine warfare six months after the war began in February 1915.

[12] While the British Royal Navy frequently violated America's neutral rights by defining contraband very broadly in their naval blockade of Germany, German submarine warfare threatened American lives.

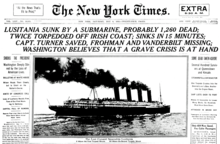

The sinking of a large, unarmed passenger ship, combined with the previous stories of atrocities in Belgium, shocked Americans and turned public opinion hostile to Germany, although not yet to the point of war.

By January 1917, however, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff decided that an unrestricted submarine blockade was the only way to achieve a decisive victory.

After President Wilson issued his declaration of war, the companies were subjected to price controls created by the US Trade Commission in order to insure that the US armed forces would have access to the necessary armaments.

At the far-left end of the political spectrum, the Socialists, led by their perennial candidate for President, Eugene V. Debs, and movement veterans like Victor L. Berger and Morris Hillquit, were staunch anti-militarists.

However, after the US joined the war in April 1917, a schism developed between the anti-war party leadership and a pro-war faction of socialist writers and intellectuals led by John Spargo, William English Walling and E. Haldeman-Julius.

This nominally-progressive group reluctantly supported US entry into the war against Germany, with the postwar goal of establishing strong international institutions designed to peacefully resolve future conflicts between nations and to promote liberal democratic values more broadly.

[33][34][35] Samuel Gompers, head of the AFL labor movement, denounced the war in 1914 as "unnatural, unjustified, and unholy", but by 1916 he was supporting Wilson's limited preparedness program, against the objections of Socialist union activists.

Preparedness was not needed because Americans were already safe, he insisted in January 1915: Educated, urban, middle-class southerners generally supported entering the war, and many worked on mobilization committees.

Led by Governor Richard I. Manning, the cities of Greenville, Spartanburg, and Columbia had started lobbying for army training centers in their communities, for both economic and patriotic reasons, in preparation for US entry into the war.

"[57][58][59] German Americans by this time usually had only weak ties to Germany; however, they were fearful of negative treatment they might receive if the United States entered the war (such mistreatment was already happening to German-descent citizens in Canada and Australia).

[64] A concerted effort was made by pacifists including Jane Addams, Oswald Garrison Villard, David Starr Jordan, Henry Ford, Lillian Wald, and Carrie Chapman Catt.

At the time, heavily Catholic towns and cities in the East and Midwest often contained multiple parishes, each serving a single ethnic group, such as Irish, German, Italian, Polish, or English.

[citation needed] New York City, with its Jewish community numbering 1.5 million, was a center of antiwar activism, much of which was organized by labor unions which were primarily on the political left and therefore opposed to a war that they viewed to be a battle between several great powers.

[79] Though an ideological proponent of self-determination in general, Wilson saw the Irish situation purely as an internal affair of the United Kingdom and did not perceive the dispute and the unrest in Ireland as one in the same as that being faced by the various other nationalities in Europe as a fall-out from World War I.

[82] Large numbers of Hungarian immigrants who were liberal and nationalist in sentiment, and sought an independent Hungary, separate from the Austro-Hungarian Empire lobbied in favor of the war and allied themselves with the Atlanticist or Anglophile portion of the population.

Four days after the ship arrived in neutral Norway, a beleaguered and physically ill Ford abandoned the mission and returned to the United States; he had demonstrated that independent small efforts accomplished nothing.

[91] On July 24, 1915, the German embassy's commercial attaché, Heinrich Albert, left his briefcase on a train in New York City, where an alert Secret Service agent, Frank Burke, snatched it up.

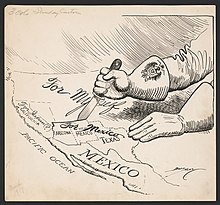

Berlin's top espionage agent, debonnaire Franz Rintelen von Kleist was spending millions to finance sabotage in Canada, stir up trouble between the United States and Mexico and to incite labor strikes.

[95] Proponents argued that the United States needed to immediately build up strong naval and land forces for defensive purposes; an unspoken assumption was that the US would fight sooner or later.

Indeed, there emerged an "Atlanticist" foreign policy establishment, a group of influential Americans drawn primarily from upper-class lawyers, bankers, academics, and politicians of the Northeast, committed to a strand of Anglophile internationalism.

[96] The Preparedness movement had a "realistic" philosophy of world affairs—they believed that economic strength and military muscle were more decisive than idealistic crusades focused on causes like democracy and national self-determination.

[98] Underscoring its commitment, the Preparedness movement set up and funded its own summer training camps at Plattsburgh, New York, and other sites, where 40,000 college alumni became physically fit, learned to march and shoot, and ultimately provided the cadre of a wartime officer corps.

Peace leaders like Jane Addams of Hull House and David Starr Jordan of Stanford redoubled their efforts, and now turned their voices against the president because he was "sowing the seeds of militarism, raising up a military and naval caste".

Many ministers, professors, farm spokesmen, and labor union leaders joined in, with powerful support from Claude Kitchin and his band of four dozen southern Democrats in Congress who took control of the House Military Affairs Committee.

[122] The interpretation was popular among left-wing Progressives (led by Senator Robert La Follette of Wisconsin) and among the "agrarian" wing of the Democratic party—including the chairman of the tax-writing Ways and Means Committee of the House.

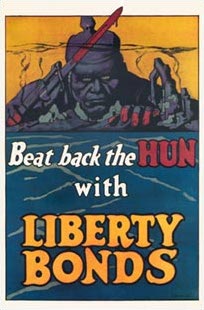

Compounding the Belgium atrocities were new weapons that Americans found repugnant, like poison gas and the aerial bombardment of innocent civilians as Zeppelins dropped bombs on London.