Loyalist (American Revolution)

Loyalists were colonists in the Thirteen Colonies who remained loyal to the British Crown during the American Revolution, often referred to as Tories,[1][2] Royalists, or King's Men at the time.

Maryland lawyer Daniel Dulaney the Younger opposed taxation without representation but would not break his oath to the king or take up arms against him.

Approximately half the colonists of European ancestry tried to avoid involvement in the struggle—some of them deliberate pacifists, others recent immigrants, and many more simple apolitical folk.

The oppression by the local Whigs during the Regulation led to many of the residents of backcountry North Carolina sitting out the Revolution or siding with the Loyalists.

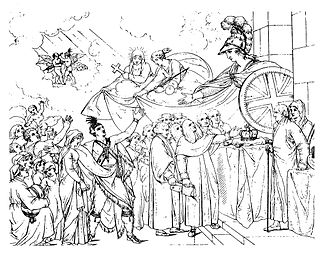

[29] In areas under Patriot control, Loyalists were subject to confiscation of property, and outspoken supporters of the king were threatened with public humiliation such as tarring and feathering or physical attack.

In September 1775, William Drayton and Loyalist leader Colonel Thomas Fletchall signed a treaty of neutrality in the interior community of Ninety Six, South Carolina.

[30] For actively aiding the British army when it occupied Philadelphia, two residents of the city were tried for treason, convicted, and executed by returning Patriot forces.

[31] As a result of the looming crisis in 1775, Royal Governor of Virginia Lord Dunmore issued a proclamation that promised freedom to indentured servants and slaves who were able to bear arms and join his Loyalist Ethiopian Regiment.

[33] At the end of the war, many Loyalist men left America for the shelter of England, leaving their wives and daughters to protect their land.

[33] The main punishment for Loyalist families was the expropriation of property, but married women were protected under "feme covert", which meant that they had no political identity and their legal rights were absorbed by their husbands.

John Brown, an agent of the Boston Committee of Correspondence,[37] worked with Canadian merchant Thomas Walker and other Patriot sympathisers during the winter of 1774–75 to convince inhabitants to support the actions of the First Continental Congress.

French Canadians had been satisfied by the British government's Quebec Act of 1774, which offered religious and linguistic toleration; in general, they did not sympathize with a revolution that they saw as being led by Protestants from New England, who were their commercial rivals and hereditary enemies.

The older British colonies, Newfoundland and Nova Scotia (including what is now New Brunswick) also remained loyal and contributed military forces in support of the Crown.

[39] Britain in any case built up powerful forces at the naval base of Halifax after the failure of Jonathan Eddy to capture Fort Cumberland in 1776.

The British provincial line, consisting of Americans enlisted on a regular army status, enrolled 19,000 Loyalists (50 units and 312 companies).

In Canada, although the Continentals captured Montreal in November 1775, they were turned back a month later at Quebec City by a combination of the British military under Governor Guy Carleton, the difficult terrain and weather, and an indifferent local response.

For the rest of the war, Quebec acted as a base for raiding expeditions, conducted primarily by Loyalists and Indians, against frontier communities.

Loyalists whose roots were not yet deeply embedded in the United States were more likely to leave; older people who had familial bonds and had acquired friends, property, and a degree of social respectability were more likely to remain in the US.

In another migration-motivated mainly by economic rather than political reasons-[54] more than 20,000 and perhaps as many as 30,000 "Late Loyalists" arrived in Ontario in the 1790s attracted by Lieutenant-Governor Simcoe's policy of land and low taxes, one-fifth those in the US and swearing an oath[when?]

[55] "They [the Loyalists]", Colonel Thomas Dundas wrote in 1786, "have experienced every possible injury from the old inhabitants of Nova Scotia, who are even more disaffected towards the British Government than any of the new States ever were.

Realizing the importance of some type of consideration, on November 9, 1789, Governor of Quebec Lord Dorchester declared that it was his wish to "put the mark of Honour upon the Families who had adhered to the Unity of the Empire."

As a result of Dorchester's statement, the printed militia rolls carried the notation: Those Loyalists who have adhered to the Unity of the Empire, and joined the Royal Standard before the Treaty of Separation in the year 1783, and all their Children and their Descendants by either sex, are to be distinguished by the following Capitals, affixed to their names: U.E.

Their ties to Britain and/or their antipathy to the United States provided the strength needed to keep Canada independent and distinct in North America.

The new British North American provinces of Upper Canada (the forerunner of Ontario) and New Brunswick were founded as places of refuge for the United Empire Loyalists.

[58] In an interesting historical twist Peter Matthews, a son of Loyalists, participated in the Upper Canada Rebellion which sought relief from oligarchic British colonial government and pursued American style republicanism.

Simcoe desired to demonstrate the merits of loyalism and abolitionism in Upper Canada in contrast to the nascent republicanism and prominence of slavery in the United States, and, according to historian Stanley R. Mealing: "...he had not only the most articulate faith in its imperial destiny but also the most sympathetic appreciation of the interests and aspirations of its inhabitants".

[67][68] The great majority of Loyalists never left the United States; they stayed on and were allowed to be citizens of the new country, retaining for a time the earlier designation of "Tories".

Captain Benjamin Hallowell, who as Mandamus Councilor in Massachusetts served as the direct representative of the Crown, was considered by the insurgents as one of the most hated men in the Colony, but as a token of compensation when he returned from England in 1796, his son was allowed to regain the family house.

[70] In many states, moderate Whigs, who had not been in favor of separation from Britain but preferred a negotiated settlement which would have maintained ties to the Mother Country, aligned with Tories to block radicals.

South Carolina, which had seen a bitter bloody internal civil war in 1780–82, adopted a policy of reconciliation that proved more moderate than any other state.