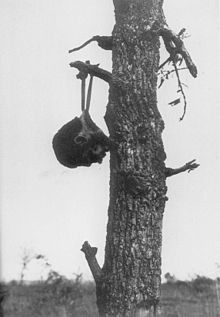

American mutilation of Japanese war dead

During World War II, members of the United States military mutilated dead and injured (hors de combat) Japanese service personnel in the Pacific theater.

This, compounded by a previous Life magazine picture of a young woman with a skull trophy, was reprinted in the Japanese media and presented as a symbol of American barbarism, causing national shock and outrage.

A number of firsthand accounts, including those of American servicemen, attest to the taking of body parts as "trophies" from the corpses of Imperial Japanese troops in the Pacific Theater during World War II.

[citation needed] The taking of so-called "trophies" was widespread enough that, by September 1942, the Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet ordered that "No part of the enemy's body may be used as a souvenir", and any American servicemen violating that principle would face "stern disciplinary action".

[10] U.S. Marine Corps veteran Donald Fall attributed the mutilation of enemy corpses to hatred and desire for vengeance: On the second day of Guadalcanal we captured a big Jap bivouac with all kinds of beer and supplies ...

[11]Another example of mutilation was related by Ore Marion, a U.S. marine who suggested that soldiers became "like animals" under harsh conditions: We learned about savagery from the Japanese ...

[7] In 1944, the American poet Winfield Townley Scott was working as a reporter in Rhode Island when a sailor displayed his skull trophy in the newspaper office.

[7] Lindbergh also noted in his diary his experiences from an air base in New Guinea, where, according to him, the troops killed the remaining Japanese stragglers "as a sort of hobby" and often used their leg-bones to carve utilities.

[18] According to Harrison only a minority of U.S. troops collected Japanese body parts as trophies, but "their behaviour reflected attitudes which were very widely shared".

[7] In contrast, Niall Ferguson states that "boiling the flesh off enemy [Japanese] skulls to make souvenirs was not an uncommon practice.

[24] The collection of Japanese body parts began quite early in the campaign, prompting a September 1942 order for disciplinary action against such souvenir taking.

He was told after expressing some shock at the question that it had become a routine point,[25] because of the large number of souvenir bones discovered in customs, also including "green" (uncured) skulls.

[26] According to Simon Harrison, all of the "trophy skulls" from the World War II era in the forensic record in the U.S., attributable to an ethnicity, are of Japanese origin; none come from Europe.

[30] According to Johnston, Australian soldiers' "unusually murderous behaviour" towards their Japanese opponents (such as summary executions) was caused by widespread racism, a lack of understanding of Japanese military culture (which also considered the enemy, especially those who surrendered, as unworthy of compassion) and, most significantly, a desire to take revenge against the murder and mutilation of Australian prisoners and native New Guineans during the Battle of Milne Bay and subsequent battles.

[34] Although there were objections to the mutilation from among other military jurists, "to many Americans the Japanese adversary was no more than an animal, and abuse of his remains carried with it no moral stigma".

[38] War correspondent Ernie Pyle, on a trip to Saipan after the invasion, claimed that the men who actually fought the Japanese did not subscribe to the wartime propaganda: "Soldiers and Marines have told me stories by the dozen about how tough the Japs are, yet how dumb they are; how illogical and yet how uncannily smart at times; how easy to rout when disorganized, yet how brave ... As far as I can see, our men are no more afraid of the Japs than they are of the Germans.

[45] Weingartner writes, however, that U.S. Marines were intent on taking gold teeth and making keepsakes of Japanese ears already while they were en route to Guadalcanal.

[9] Pictures showing the "cooking and scraping" of Japanese heads may have formed part of the large set of Guadalcanal photographs sold to sailors which were circulating on the U.S.

[47] According to Paul Fussell, pictures showing this type of activity, i.e. boiling human heads, "were taken (and preserved for a lifetime) because the Marines were proud of their success".

"[41] Another example of that type of press is Yank, which, in early 1943, published a cartoon showing the parents of a soldier receiving a pair of ears from their son.

[41] Harrison also makes note of the Congressman that gave President Roosevelt a letter-opener carved out of bone as examples of the social range of these attitudes.

[40] "Stern disciplinary action" against human remains souvenir taking was ordered by the Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet as early as September 1942.

[48] Simon Harrison writes that directives of this type may have been effective in some areas, "but they seem to have been implemented only partially and unevenly by local commanders".

The image caption stated: "When he said goodbye two years ago to Natalie Nickerson, 20, a war worker of Phoenix, Ariz., a big, handsome Navy lieutenant promised her a Jap.

Last week Natalie received a human skull, autographed by her lieutenant and 13 friends, and inscribed: "This is a good Jap – a dead one picked up on the New Guinea beach."

In a memorandum dated June 13, 1944, the Army JAG asserted that "such atrocious and brutal policies" in addition to being repugnant also were violations of the laws of war, and recommended the distribution to all commanders of a directive pointing out that "the maltreatment of enemy war dead was a blatant violation of the 1929 Geneva Convention on the Sick and Wounded, which provided that: After each engagement, the occupant of the field of battle shall take measures to search for the wounded and dead, and to protect them against pillage and maltreatment."

[54] The Navy JAG mirrored that opinion one week later, and also added that "the atrocious conduct of which some U.S. servicemen were guilty could lead to retaliation by the Japanese which would be justified under international law".

[54] On June 13, 1944, the press reported that President Roosevelt had been presented with a letter-opener made out of a Japanese soldier's arm bone by Francis E. Walter, a Democratic congressman.

That reporting was compounded by the previous May 22, 1944, Life magazine picture of the week publication of a young woman with a skull trophy, which was reprinted in the Japanese media and presented as a symbol of American barbarism, causing national shock and outrage.

This aspect of Shinto, combined with the propaganda spotlight on American atrocities, contributed directly to the mass suicides on Saipan and Okinawa after the Allied landings.