Amharic

It is spoken as a first language by the Amharas, and also serves as a lingua franca for all other populations residing in major cities and towns in Ethiopia.

[13] The segmental writing system in which consonant-vowel sequences are written as units is called an abugida (አቡጊዳ).

The Amharic examples in the sections below use one system that is common among linguists specializing in Ethiopian Semitic languages.

[15] The appellation of "language of the king" (Ge'ez: ልሳነ ነጋሢ; "Lǝssanä nägaśi," Amharic: የነጋሢ ቋንቋ "Yä-nägaśi qʷanqʷa") and its use in the royal court are otherwise traced to the Amhara Emperor Yekuno Amlak.

Shortly afterwards, the proto-Cushitic and proto-Omotic groups would have settled in the Ethiopian highlands, with the proto-Semitic speakers crossing the Sinai Peninsula into Asia.

[25] Based on archaeological evidence, the presence of Semitic speakers in the territory date to some time before 500 BC.

Levine indicates that by the end of that millennium, the core inhabitants of Greater Ethiopia would have consisted of dark-skinned agropastoralists speaking Afro-Asiatic languages of the Semitic, Cushitic and Omotic branches.

[25] Other scholars such as Messay Kebede and Daniel E. Alemu argue that migration across the Red Sea was defined by reciprocal exchange, if it even occurred at all, and that Ethio-Semitic-speaking ethnic groups should not be characterized as foreign invaders.

[29][30][31] Due to the social stratification of the time, the Cushitic Agaw adopted the South Ethio-Semitic language and eventually absorbed the Semitic population.

[38][39] A 7th century southward shift of the center of gravity of the Kingdom of Aksum and the ensuing integration and Christianization of the proto-Amhara also resulted in a high prevalence of Geʽez sourced lexicon in Amharic.

[43] In 1983, Lionel Bender proposed that Amharic may have been constructed as a pidgin as early as the 4th century AD to enable communication between Aksumite soldiers speaking Semitic, Cushitic, and Omotic languages, but this hypothesis has not garnered widespread acceptance.

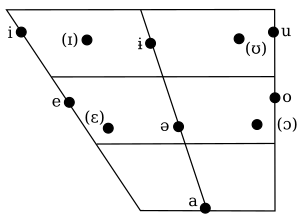

The closed central unrounded vowel ⟨ə⟩ /ɨ/ and mid-central vowel ⟨ä⟩ /ə/ are generally fronted to [ɪ] and [ɛ], respectively, following palatal consonants, and generally retracted and rounded to [ʊ] and [ɔ], respectively, following labialized velar consonants.

Amharic is a pro-drop language: neutral sentences in which no element is emphasized normally omit independent pronouns: ኢትዮጵያዊ ነው ʾityop̣p̣yawi näw 'he's Ethiopian', ጋበዝኳት gabbäzkwat 'I invited her'.

However, in such cases, the person, number, and (second- or third-person singular) gender of the subject and object are marked on the verb.

The choice depends on what precedes the form in question, usually whether this is a vowel or a consonant, for example, for the first-person singular possessive suffix, ሀገሬ hagär-e 'my country', ገላዬ gäla-ye 'my body'.

Within second- and third-person singular, there are two additional polite independent pronouns, for reference to people to whom the speaker wishes to show respect.

), Amharic adds the independent pronouns to the preposition yä- 'of': የኔ yäne 'mine', ያንተ yantä 'yours m.

), Amharic adds the possessive suffixes to the noun ራስ ras 'head': ራሴ rase 'myself', ራሷ raswa 'herself', etc.

Like English, Amharic makes a two-way distinction between near ('this, these') and far ('that, those') demonstrative expressions (pronouns, adjectives, adverbs).

The singular pronouns have combining forms beginning with zz instead of y when they follow a preposition: ስለዚህ sǝläzzih 'because of this; therefore', እንደዚያ ǝndäzziya 'like that'.

This suffix also occurs in nouns and adjective based on the pattern qǝt(t)ul, e.g. nǝgus 'king' vs. nǝgǝs-t 'queen' and qǝddus 'holy (m.)' vs. qǝddǝs-t 'holy (f.)'.

Some nouns and adjectives take a feminine marker -it: lǝǧ 'child, boy' vs. lǝǧ-it 'girl'; bäg 'sheep, ram' vs. bäg-it 'ewe'; šǝmagǝlle 'senior, elder (m.)' vs. šǝmagǝll-it 'old woman'; ṭoṭa 'monkey' vs. ṭoṭ-it 'monkey (f.)'.

For nouns ending in a back vowel (-a, -o, -u), the suffix takes the form -ʷočč, e.g. wǝšša 'dog', wǝšša-ʷočč 'dogs'; käbäro 'drum', käbäro-ʷočč 'drums'.

Adjectives in Amharic can be formed in several ways: they can be based on nominal patterns, or derived from nouns, verbs and other parts of speech.

In Amharic, the adjective precedes the noun, with the verb last; e.g. kǝfu geta 'a bad master'; təlləq bet särra (lit.

[52] Haddis Alemayehu (1910–2003), foreign minister and novelist, including author of Love to the Grave, considered the greatest novel in Ethiopian literature.The oldest surviving examples of written Amharic date back to the reigns of the 14th century Emperor of Ethiopia Amda Seyon I and his successors, who commissioned a number of poems known as "የወታደሮች መዝሙር" (Soldier songs) glorifying them and their troops.

This literature includes government proclamations and records, educational books, religious material, novels, poetry, proverb collections, dictionaries (monolingual and bilingual), technical manuals, medical topics, etc.

The most famous Amharic novel is Fiqir Iske Meqabir (transliterated various ways) by Haddis Alemayehu (1909–2003), translated into English by Sisay Ayenew with the title Love unto Crypt, published in 2005 (ISBN 978-1-4184-9182-6).

[56] Various reggae artists in the 1970s, including Ras Michael, Lincoln Thompson and Misty in Roots, have sung in Amharic, thus bringing the language to a wider audience.

The word "satta" has become a common expression in the Rastafari dialect of English, Iyaric, meaning "to sit down and partake".