Roald Amundsen

Born in Borge, Østfold, Norway, Amundsen began his career as a polar explorer as first mate on Adrien de Gerlache's Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–1899.

His party established a camp at the Bay of Whales and a series of supply depots on the Barrier (now known as the Ross Ice Shelf) before setting out for the pole in October.

Following a failed attempt in 1918 to reach the North Pole by traversing the Northeast Passage on the ship Maud, Amundsen began planning for an aerial expedition instead.

[7] Amundsen was in the Uranienborg neighbourhood an occasional childhood playmate of the pioneering Antarctica explorer Carsten Borchgrevink.

[8][9] When he was fifteen years old, Amundsen was enthralled by reading Sir John Franklin's narratives of his overland Arctic expeditions.

[11] The Belgica, whether by mistake or design, became locked in the sea ice at 70°30′S off Alexander Island, west of the Antarctic Peninsula.

[11][13] During this time, Amundsen and the crew learned from the local Netsilik Inuit about Arctic survival skills, which he found invaluable in his later expedition to the South Pole.

For example, he learned to use sled dogs for the transport of goods and to wear animal skins in lieu of heavy, woolen parkas, which could not keep out the cold when wet.

Finding it difficult to raise funds, when he heard in 1909 that the Americans Frederick Cook and Robert Peary had claimed to reach the North Pole as a result of two different expeditions, he decided to reroute to Antarctica.

Amundsen eschewed the heavy wool clothing worn on earlier Antarctic attempts in favour of adopting Inuit-style furred skins.

[18] A small group, including Hjalmar Johansen, Kristian Prestrud and Jørgen Stubberud, set out on 8 September, but had to abandon their trek due to extreme temperatures.

The painful retreat caused a quarrel within the group, and Amundsen sent Johansen and the other two men to explore King Edward VII Land.

A second attempt, with a team of five made up of Olav Bjaaland, Helmer Hanssen, Sverre Hassel, Oscar Wisting and Amundsen, departed base camp on 19 October.

Using a route along the previously unknown Axel Heiberg Glacier, they arrived at the edge of the Polar Plateau on 21 November after a four-day climb.

Amundsen's expedition benefited from his careful preparation, good equipment, appropriate clothing, a simple primary task, an understanding of dogs and their handling, and the effective use of skis.

In contrast to Amundsen's earlier expeditions, this was expected to yield more material for academic research, and he carried the geophysicist Harald Sverdrup on board.

Amundsen planned to freeze the Maud into the polar ice cap and drift towards the North Pole – as Nansen had done with the Fram – and he did so off Cape Chelyuskin.

After two winters frozen in the ice, without having achieved the goal of drifting over the North Pole, Amundsen decided to go to Nome to repair the ship and buy provisions.

Much of the carefully collected scientific data was lost during the ill-fated journey of Peter Tessem and Paul Knutsen, two crew members sent on a mission by Amundsen.

The scientific materials were later retrieved in 1922 by Russian scientist Nikolay Urvantsev from where they had been abandoned on the shores of the Kara Sea.

Amundsen and Oskar Omdal, of the Royal Norwegian Navy, tried to fly from Wainwright, Alaska, to Spitsbergen across the North Pole.

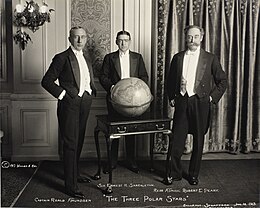

The three previous claims to have arrived at the North Pole, by the Americans Frederick Cook in 1908; Robert Peary in 1909; and Richard E. Byrd in 1926 (just a few days before the Norge) are disputed by some, as being either of dubious accuracy or outright fraudulent.

It is assumed that the plane crashed in the Barents Sea,[31] and that Amundsen and his crew were killed in the wreck, or died shortly afterward.

[32] In 2004 and in late August 2009, the Royal Norwegian Navy used the unmanned submarine Hugin 1000 to search for the wreckage of Amundsen's plane.

[39] Owing to Amundsen's numerous significant accomplishments in polar exploration, many places in both the Arctic and Antarctic are named after him.

The Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station, operated by the United States Antarctic Program, was jointly named in honour of Amundsen and his British rival Robert Falcon Scott.

[58] At least two Inuit in Gjøa Haven with European ancestry have claimed to be descendants of Amundsen, from the period of their extended winter stay on King William Island from 1903 to 1905.

[59] Accounts by members of the expedition told of their relations with Inuit women, and historians have speculated that Amundsen might also have taken a partner,[60] although he wrote a warning against this.

Konona said that their father Ikuallaq was left out on the ice to die after his birth, as his European ancestry made him illegitimate to the Inuit, threatening their community.

In 2012, Y-DNA analysis, with the families' permission, showed that Ikuallaq was not a match to the direct male line of Amundsen.