Anatolie Popa

He was supportive of the overthrow of the Tsar during the February Revolution, and his political views were further influenced by the strong Bolshevik agitation in the 49th Technical Reserve Battalion in Odessa, where he was recovering from a battlefield injury.

[4] The October Revolution, however, led to a mood change amongst the more moderate leftist groups, and in November 1917 the various revolutionary committees coagulated into a provisional provincial assembly, Sfatul Țării, which on 15 December [O.S.

[6] As the latter commanded the allegiance of most regular troops of the Russian Army in Bessarabia, increasingly Bolshevik in outlook, the Council of Directors sought to enlist the Moldavian militias in an effort to create an Armed Force loyal to Sfatul Țării.

The Soviet and the Council still collaborated in managing the demobilisation, however they were unable to cope with the disruption caused by the large number of disorganised, badly fed soldiers leaving the front.

[12] Confronted with widespread peasant rioting and the unreliability of Moldavian troops, which were also siding with the Bolsheviks, a closed session of Sfatul Țării authorised the Council of Directors to look for military support outside the province: the leftist leaders, Ion Inculeț and Pantelimon Erhan, held talks with the chief of the Odessa Military District, while the nationalist MNP sought assistance from the Romanian government in Iași.

20 December 1917], rumours of an imminent foreign military intervention had spread in Chișinău, prompting the Moldavian Military Central Executive Committee, the City Soviet and the provincial Peasants' Council to issue protests, affirming their commitment to the revolution and a federal Russia, and calling for redistributing land to peasants, purging the "reactionary" elements in Sfatul Țării and establishing relations with the Sovnarkom.

[14] In spite of reassurances coming from the leaders of Sfatul Țării that only "neutral" troops would be brought, the provincial and Chișinău City soviets took steps toward strengthening their positions.

Several leaders of the Nationalist Party would later testify this was the intended course of events, the Council fearing a direct call for Romanian troops would result in a popular revolt.

[16] In this context, the Romanian army moved in into Bessarabia in early January and occupied several towns and villages along the Prut, encountering only light resistance from local pro-Soviet troops.

[17] The mood among the Moldavian troops was also strongly anti-Romanian, and Erhan and the Military Director, Gherman Pântea, were forced to authorise resistance; however, as the main corps of the Romanian army approached Chișinău on 20 January [O.S.

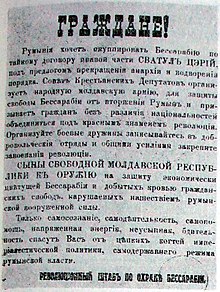

[24] In spite of such opposition, Rudiev and Popa, who replaced the former in the Revolutionary Headquarters, handed out weapons to volunteers in the city and nearby villages and ensured that the two artillery pieces available to the garrison were properly manned.

14 January], voted to reject the authority of Sfatul Țării as unrepresentative, pledged allegiance to the Bolshevik Sovnarkom and called for the institution of Soviet power.

Furthermore, the Congress rejected Bessarabia's separation from Soviet Russia and decided to send Paladi to Petrograd to request for military assistance against the Romanian intervention.

Noting that the population was outraged by the Romanian intervention and the Peasants' Council had switched allegiance to the Petrograd government, he requested more officers and money for the soldiers' pay, and offered to send ammunitions and even troops to Chișinău.

In his reply, Pântea repeated the Romanian argument that their intervention was only meant to protect the supply depots and pacify the capital, and expressed his distrust of the Bolshevik government.

Furthermore, Pântea informed Popa about his intention to resign from the executive, as the latter was becoming increasingly pro-Romanian, as well as his decision to mobilise the Moldavian Army to defend the country in case "someone looks over the Prut", towards the Romanian government.

[31] The defenders of the city, comprising up to a thousand volunteers and the revolutionary troops in the garrison, were also joined by armed peasants from Cubolta, Hăsnășenii Mici and other nearby villages.

[31] As argued by historian Izeaslav Levit, the opponents of the Romanian intervention included people of different ethnic backgrounds and political options: while the chairman of the local Soviet, the Ukrainian lieutenant Soloviev, collaborated with the Revolutionary Headquarters chiefly in order to prevent its takeover by the Bolsheviks, the Moldavians Rudiev and Popa were primarily supporters of the Moldavian autonomy and of peasants' interest, pushed into collaboration with the Bolsheviks by what they saw as their betrayal by the right wing of the Sfatul Țării.

This Red Army unit included many participants in the Khotyn Uprising, and was later redesignated as a Special Bessarabian Brigade and in June was integrated into the newly organised 45th Soviet Rifle Division.

Under the command of Bessarabian Yona Yakir, the division fought in the Southern Campaign of the Russian Civil War; after the fall of Odessa, it took a 400 kilometre march across enemy lines, engaging along the way the forces of Yudenich, Denikin and Makhno.