Ancient Greek accent

The most famous of these, Aelius Herodianus or Herodian, who lived and taught in Rome in the 2nd century AD, wrote a long treatise in twenty books, 19 of which were devoted to accentuation.

Latin accentus corresponds to Greek προσῳδία prosōidía "song sung to instrumental music, pitch variation in voice"[10] (the word from which English prosody comes), acūtus to ὀξεῖα oxeîa "sharp" or "high-pitched",[11] gravis to βαρεῖα bareîa "heavy" or "low-pitched",[12] and circumflexus to περισπωμένη perispōménē "pulled around" or "bent".

As long ago as the 19th century it was surmised that in a word with recessive accent the pitch may have fallen not suddenly but gradually in a sequence high–middle–low, with the final element always short.

The first is the statements of Greek grammarians, who consistently describe the accent in musical terms, using words such as ὀξύς oxús 'high-pitched' and βαρύς barús 'low-pitched'.

When the accent is a circumflex, the music often shows a fall from a higher note to a lower one within the syllable itself, exactly as described by Dionysius of Halicarnassus; examples are the words Μουσῶν Mousôn 'of the Muses' and εὐμενεῖς eumeneîs 'favourable' in the prayer illustrated above.

[28] There is sometimes a jump up from a lower note, as in the word μειγνύμενος meignúmenos 'mingling' from the second hymn; more often there is a gradual rise, as in Κασταλίδος Kastalídos 'of Castalia', Κυνθίαν Kunthían 'Cynthian', or ἀνακίδναται anakídnatai 'spreads upwards': In some cases, however, before the accent instead of a rise there is a 'plateau' of one or two notes the same height as the accent itself, as in Παρνασσίδος Parnassídos 'of Parnassus', ἐπινίσεται epinísetai 'he visits', Ῥωμαίων Rhōmaíōn 'of the Romans', or ἀγηράτῳ agērátōi 'ageless' from the Delphic hymns: Anticipation of the high tone of an accent in this way is found in other pitch-accent languages, such as some varieties of Japanese,[29] Turkish,[30] or Serbian,[31] where for example the word papríka 'pepper' can be pronounced pápríka.

in the Seikilos epitaph, or Σελάνα Selána 'the Moon' in the Hymn to the Sun, in which the syllable with the acute is set to a melism of two or three notes rising gradually.

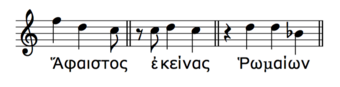

More frequently, however, on an accented long vowel in the music there is no rise in pitch, and the syllable is set to a level note, as in the words Ἅφαιστος Háphaistos 'Hephaestus' from the 1st Delphic hymn or ἐκείνας ekeínas 'those' or Ῥωμαίων Rhōmaíōn 'of the Romans' from the 2nd hymn: Because this is so common, it is possible that at least sometimes the pitch did not rise on a long vowel with an acute accent but remained level.

Another consideration is that although the ancient grammarians regularly describe the circumflex accent as 'two-toned' (δίτονος) or 'compound' (σύνθετος) or 'double' (διπλοῦς), they usually do not make similar remarks about the acute.

Examples are ἔχεις τρίποδα ékheis trípoda 'you have a tripod' or μέλπετε δὲ Πύθιον mélpete dè Púthion 'sing the Pythian' in the 2nd Delphic hymn.

Devine and Stephens, citing a similar phenomenon in the music of the Nigerian language Hausa, comment: "This is not a mismatch but reflects a feature of phrase intonation in fluent speech.

In these phrases, the accent of the second word is higher than or on the same level as that of the first word, and just as with phrases such as ἵνα Φοῖβον hína Phoîbon mentioned above, the lack of fall in pitch appears to represent some sort of assimilation or tone sandhi between the two accents: When a circumflex occurs immediately before a comma, it also regularly has a single note in the music, as in τερπνῶν terpnôn 'delightful' in the Mesomedes' Invocation to Calliope illustrated above.

The third accentual mark used in ancient Greek was the grave accent, which is only found on the last syllable of words e.g. ἀγαθὸς ἄνθρωπος agathòs ánthrōpos 'a good man'.

This usually occurs when the word with a grave forms part of a phrase in which the music is in any case rising to an accented word, as in καὶ σοφὲ μυστοδότα kaì sophè mustodóta 'and you, wise initiator into the mysteries' in the Mesomedes prayer illustrated above, or in λιγὺ δὲ λωτὸς βρέμων, αἰόλοις μέλεσιν ᾠδὰν κρέκει ligù dè lōtòs brémōn, aiólois mélesin ōidàn krékei 'and the pipe, sounding clearly, weaves a song with shimmering melodies' in the 1st Delphic hymn: In the Delphic hymns, a grave accent is almost never followed by a note lower than itself.

For example, in the second line of the 1st Delphic Hymn, there is a gradual descent from a high pitch to a low one, followed by a jump up by an octave for the start of the next sentence.

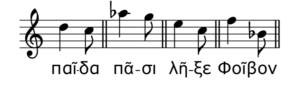

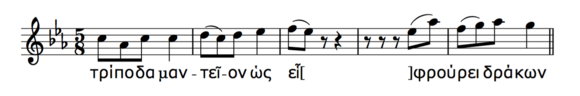

The words (mólete sunómaimon hína Phoîbon ōidaîsi mélpsēte khruseokóman) mean: 'Come, so that you may hymn with songs your brother Phoebus, the Golden-Haired': However, not all sentences follow this rule, but some have an upwards trend, as in the clause below from the first Delphic hymn, which when restored reads τρίποδα μαντεῖον ὡς εἷλ[ες ὃν μέγας ἐ]φρούρει δράκων trípoda manteîon hōs heîl[es hòn mégas e]phroúrei drákōn 'how you seized the prophetic tripod which the great snake was guarding'.

Immediately before a comma, a circumflex accent does not fall but is regularly set to a level note, as in the first line of the Seikilos epitaph, which reads 'As long as you live, shine!

Do not grieve at all': A higher pitch is also used for proper names and for emphatic words, especially in situations where a non-basic word-order indicates emphasis or focus.

If an accent comes on the antepenultimate syllable, it is always an acute, for example: Exception: ὧντινων hôntinōn 'of what sort of', in which the second part is an enclitic word.

In most cases, a final -οι -oi or -αι -ai counts as a short vowel: Otherwise the accent is an acute: Exception 1: Certain compounds made from an ordinary word and an enclitic suffix have an acute even though they have long vowel–short vowel:[59] Exception 2: In locative expressions and verbs in the optative mood a final -οι -oi or -αι -ai counts as a long vowel: The third principle of Greek accentuation is that, after taking into account the Law of Limitation and the σωτῆρα (sōtêra) Law, the accent in nouns, adjectives, and pronouns remains as far as possible on the same syllable (counting from the beginning of the word) in all the cases, numbers, and genders.

The name Δημήτηρ Dēmḗtēr 'Demeter' changes its accent to accusative Δήμητρα Dḗmētra, genitive Δήμητρος Dḗmētros, dative Δήμητρι Dḗmētri.

The nouns παῖς paîs 'boy' and Τρῶες Trôes 'Trojans' follow this pattern except in the genitive dual and plural: The adjective πᾶς pâs 'all' has a mobile accent only in the singular: Monosyllabic participles, such as ὤν ṓn 'being', and the interrogative pronoun τίς; τί; tís?

Examples in Greek are the following:[91] (a) The connective τε te 'also', 'and': (b) The emphatic particles: The pronouns ἐγώ egṓ 'I' and ἐμοί emoí 'to me' can combine with γε ge to make a single word accented on the first syllable:[56] (c) Indefinite adverbs: (d) Indefinite pronouns: But τινές tinés can also sometimes begin a sentence, in which case it is non-enclitic and has an accent on the final.

(e) The present tense (except for the 2nd person singular) of εἰμί eimí 'I am' and φημί phēmí 'I say': These verbs can also have non-enclitic forms which are used, for example, to begin a sentence or after an elision.

Judging from parallel forms in Sanskrit it is possible that originally when non-enclitic the other persons also were accented on the first syllable: *εἶμι eîmi, *φῆμι phêmi etc.

; but the usual convention, among most modern editors as well as the ancient Greek grammarians, is to write εἰμὶ eimì and φημὶ phēmì even at the beginning of a sentence.

The non-enclitic form of με, μου, μοι me, mou, moi 'me', 'of me', 'to me' is ἐμέ, ἐμοῦ, ἐμοί emé, emoû, emoí.

Except for the nominative singular of certain participles (e.g., masculine λαβών labṓn, neuter λαβόν labón 'after taking'), a few imperatives (such as εἰπέ eipé 'say'), and the irregular present tenses (φημί phēmí 'I say' and εἰμί eimí 'I am'), no parts of the verb are oxytone.

'[110] This form is used among other places in the phrase οὐκ ἔστι ouk ésti 'it is not' and at the beginning of sentences, such as: The 2nd person singular εἶ eî 'you are' and φῄς phḗis 'you say' are not enclitic.

The ancient grammarians were aware that there were sometimes differences between their own accentuation and that of other dialects, for example that of the Homeric poems, which they could presumably learn from the traditional sung recitation.