Andrew Inglis Clark

He initially qualified as an engineer, but he re-trained as a barrister to effectively fight for social causes which deeply concerned him.

After a long political career, mostly spent as Attorney-General and briefly as Opposition Leader, he was appointed a Senior Justice of the Supreme Court of Tasmania.

[1] In one summation, "Clark was an Australian Jefferson, who, like the great American Republican, fought for Australian independence; an autonomous judiciary; a wider franchise and lower property qualifications; fairer electoral boundaries; checks and balances between the judicature, legislature and executive; modern, liberal universities; and a Commonwealth that was federal, independent and based on natural rights.

"[2] Less favourably, a contemporary, J.B. Walker, privately judged him an "eloquent, impressive, dignified ... doctrinaire politician ... wanting in practical ability".

[1] He grew to manhood during the 1860s, when the major issue, even in remote Tasmania, was the American Civil War and emancipation.

The friendship formed with the latter would strongly influence his views and the development of the Clarks' draft of the Australian Constitution.

As the son of a prominent family, and a leading figure of his church who was marrying the daughter of a well-known businessman, his marriage might have been expected to be a major social event.

His election was largely due to the influence of Thomas Reibey, a political power broker and a recent Premier.

Clark failed in his attempts to impose a land tax, introduce universal (including female) suffrage and centralise the police.

His best known achievement as Attorney-General was the introduction of proportional representation based on the Hare-Clark system of the single transferable vote.

[1] With his dual qualifications as both an engineer and a lawyer, Clark was in a unique position to understand the issues involved.

When Sir Edward Braddon formed a government in 1894, Clark again became Attorney-General, the same year he was given the title 'Honourable' for life.

[1] He resigned in 1897, when his colleagues failed to consult him over the lease of Crown land to private interests, after which he became Leader of the Opposition.

Clark was a delegate to the National Australasian Convention of 1891, and was a member of its committee which produced a draft constitution.

However, he did not stand for the election of delegates to the Australian Federal Convention of 1897, and embarked on an overseas journey two days after it commenced.

The modified single transferable vote method, immediately known as the Hare–Clark system, was renewed annually until suspended in 1902.

Clark died in 1907, just as permanent proportional representation struggled through Parliament and over a year before it was used for the first time throughout Tasmania at the general election in April 1909.

He failed to find his fortune in the law due to his generosity and refusal 'to accept anything beyond a reasonable and modest fee'.

[1] His career in private practice gave him a broad grounding in the law which stood him in good stead once he was promoted to the bench.

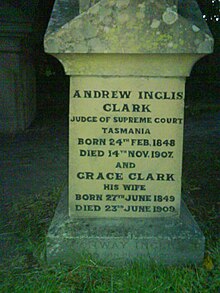

[1] Clark, never in robust health, in fact described as "small, spare, [and] nervous" by Alfred Deakin, died at his home 'Rosebank' in Battery Point on 14 November 1907.