Andrew Johnson and slavery

"[2] Johnson's engagement with Southern Unionism and Abraham Lincoln is summarized by his statement, "Damn the negroes; I am fighting these traitorous aristocrats, their masters!

Johnson peddled the racist myth that Southern whites were victimized by black emancipation and citizenship, which became an article of faith among Lost Cause proponents in the postwar South.

He tried to, but as a poor white, steeped in the limitations, prejudices, and ambitions of his social class, he could not; and this is the key to his career...For [the future of the] Negroes...he had nothing...except the bare possibility that, if given freedom, they might continue to exist and not die out.

'"[8] Similarly, in March 1869, shortly after the end of his term in the White House, a newspaperman from Cincinnati found the ex-president at his home in Greeneville and conducted an interview.

In the days when the writing was on the wall, and he knew that slavery would die at the hands of the Civil War, Johnson adopted an antislavery stance and began to denounce the institution.

"[17]If Johnson did have a shadow family with Dolly while hypocritically upholding a race-based caste system, it would have put him in the company of U.S. President Thomas Jefferson, Supreme Court Justice John Catron, sexual-predator U.S.

[26] Johnson's possibly having fathered several multiracial children would have been part of a widespread "racial and sexual double standard...in the slaveholding states [that] gave elite white men a free pass for their sexual relationships with black women, as long as the men neither flaunted nor legitimated such unions.

In addition to suspicions about his sexual exploitation of Dolly, he was accused twice in separate sworn testimonies of being familiar with sex workers;[29][30] in 1872, he was accused of seducing his neighbor's wife;[31] and he was posthumously described as the source of a "canker" in his wife's heart "fed or created, as the gossips have said, by the marital infidelity of her graceless lord.

Researchers can only speculate but not know that "perhaps intimate letters between family members revealed the identity(ies) of the father of Dolly’s offspring.

[37] According to University of Virginia history professor Elizabeth Maron, "Fearing that emancipation by federal edict would alienate Tennessee's slaveholding Unionists, Johnson urged that the state be exempted from the Emancipation Proclamation, so he could promote the issue from the inside: in August 1863, Johnson freed his own slaves, seeking to set an example for his fellow Tennesseans.

[6][39] For the many decades between emancipation and desegregation, the annual August 8 picnic was the only day of the year that blacks were allowed to be in Knoxville's Chilhowee Park.

Prior to the summer of 1863, Johnson had staunchly opposed general emancipation, but beginning in August of that year, he made a sharp heel-turn in favor of freeing the slaves.

"Before an audience of ten thousand colored men...amidst cheers which shook the sky," Johnson proclaimed that he would act for their benefit and advancement as a race now that the slaves of the United States had been emancipated.

Loyal men, whether white or black, shall alone control her destinies: and when this strife in which we are all engaged is past, I trust, I know, we shall have a better state of things, and shall all rejoice that honest labor reaps the fruit of its own industry, and that every man has a fair chance in the race of life.Johnson refers to the Biblical figure Moses from the book of Exodus, who led the enslaved Jews of ancient Egypt out of bondage with the aid of his god, who parted the Red Sea so that they might pass, and then released the waters upon their pursuers.

"[45] Per historian Robert S. Levine, "...Johnson worked to undermine the Freedmen's Bureau, to dismantle other Reconstruction initiatives, and to prevent African Americans from attaining equal rights through federal legislation.

"[46] The betrayal, which contributed to the failure of Reconstruction and another 100 years of racial oppression,[46] continues to be a central focus of historians, but was recognized and criticized in his own time.

The Memphis Argus, one of the most uncompromising rebel sheets published, said in 1862: "We should to like to see Andrew Johnson's lying tongue torn from his foul mouth, and his miserable carcass thrown to the dogs, or hung on a gibbet as high as Haman to feed the carrion buzzards."

"[48]In a report about Johnson's supposed tears over superficial gestures of national comity at the pro-Johnson 1866 National Union Convention in Philadelphia: "There is good reason to believe, that when Miss Columbia, in imitation of Miss Pharaoh, fished among the bulrushes and slimy waters of Southern plebeianism for a little Moses, she slung out a young crocodile instead.

"[49] The image that Johnson provided of himself-as-Moses was sufficiently rich that it continues to be applied with grim irony to present day.

Original partisans of slavery north and south; habitual compromisers of great principles; maligners of the Declaration of Independence; politicians without heart; lawyers, for whom a technicality is everything, and a promiscuous company who at every stage of the battle have set their faces against equal rights; these are his allies.

I would not in this judgment depart from that moderation which belongs to the occasion; but God forbid that, when called to deal with so great an offender, should affect a coldness which I cannot feel.

Slavery has been our worst enemy, assailing all, murdering our children, filling our homes with mourning, and darkening the land with tragedy; and now it rears its crest anew, with Andrew Johnson as its representative.

Far from listening amiably to Sumner's argument that the South was still torn by violence and not yet ready tor readmission, Johnson attacked him with cheap analogies.

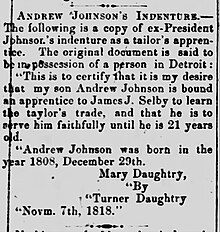

White supremacist[55] writer, magazine editor, and librarian/archivist John Trotwood Moore described teenage Johnson in a 1929 Saturday Evening Post article as a "slave-bound boy.

"[56] One study of presidential rhetorical styles argued, "no amount of success could fully compensate for the needs left from his traumatic childhood.