Andromeda Galaxy

[16] With an apparent magnitude of 3.4, the Andromeda Galaxy is among the brightest of the Messier objects,[17] and is visible to the naked eye from Earth on moonless nights,[18] even when viewed from areas with moderate light pollution.

[21] Around the year 964 CE, the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi described the Andromeda Galaxy in his Book of Fixed Stars as a "nebulous smear" or "small cloud".

[23] In 1612, the German astronomer Simon Marius gave an early description of the Andromeda Galaxy based on telescopic observations.

[25] Charles Messier cataloged Andromeda as object M31 in 1764 and incorrectly credited Marius as the discoverer despite it being visible to the naked eye.

[28] The spectrum of Andromeda displays a continuum of frequencies, superimposed with dark absorption lines that help identify the chemical composition of an object.

[33] As early as 1755, the German philosopher Immanuel Kant proposed the hypothesis that the Milky Way is only one of many galaxies in his book Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens.

[37] In 1920, the Great Debate between Harlow Shapley and Curtis took place concerning the nature of the Milky Way, spiral nebulae, and the dimensions of the universe.

[29] Edwin Hubble settled the debate in 1925 when he identified extragalactic Cepheid variable stars for the first time on astronomical photos of Andromeda.

)[39] Baade also discovered that there were two types of Cepheid variable stars, which resulted in doubling the distance estimate to Andromeda, as well as the remainder of the universe.

[40] In 1950, radio emissions from the Andromeda Galaxy were detected by Robert Hanbury Brown and Cyril Hazard at the Jodrell Bank Observatory.

[49][50] A major merger occurred 2 to 3 billion years ago at the Andromeda location, involving two galaxies with a mass ratio of approximately 4.

During this epoch, its rate of star formation would have been very high, to the point of becoming a luminous infrared galaxy for roughly 100 million years.

Andromeda and the Triangulum Galaxy (M33) might have had a very close passage 2–4 billion years ago, but it seems unlikely from the last measurements from the Hubble Space Telescope.

In 2003, using the infrared surface brightness fluctuations (I-SBF) and adjusting for the new period-luminosity value and a metallicity correction of −0.2 mag dex−1 in (O/H), an estimate of 2.57 ± 0.06 million ly (162.5 ± 3.8 billion AU) was derived.

[d] Until 2018, mass estimates for the Andromeda Galaxy's halo (including dark matter) gave a value of approximately 1.5×1012 M☉,[58] compared to 8×1011 M☉ for the Milky Way.

[66] The radio results (similar mass to the Milky Way Galaxy) should be taken as likeliest as of 2018, although clearly, this matter is still under active investigation by several research groups worldwide.

Star formation activity in green valley galaxies is slowing as they run out of star-forming gas in the interstellar medium.

The most commonly employed is the D25 standard, the isophote where the photometric brightness of a galaxy in the B-band (445 nm wavelength of light, in the blue part of the visible spectrum) reaches 25 mag/arcsec2.

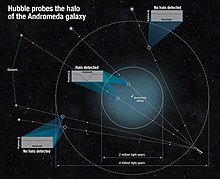

[86] A study in 2005 by the Keck telescopes shows the existence of a tenuous sprinkle of stars, or galactic halo, extending outward from the galaxy.

Spectroscopic studies have provided detailed measurements of the rotational velocity of the Andromeda Galaxy as a function of radial distance from the core.

[88] The spiral arms of the Andromeda Galaxy are outlined by a series of HII regions, first studied in great detail by Walter Baade and described by him as resembling "beads on a string".

[95] Close examination of the inner region of the Andromeda Galaxy with the same telescope also showed a smaller dust ring that is believed to have been caused by the interaction with M32 more than 200 million years ago.

[107] It has been proposed that the observed double nucleus could be explained if P1 is the projection of a disk of stars in an eccentric orbit around the central black hole.

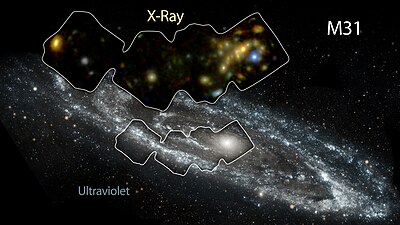

The A stars are not evident in redder filters, but in blue and ultraviolet light they dominate the nucleus, causing P2 to appear more prominent than P1.

[110] While at the initial time of its discovery it was hypothesized that the brighter portion of the double nucleus is the remnant of a small galaxy "cannibalized" by the Andromeda Galaxy,[111] this is no longer considered a viable explanation, largely because such a nucleus would have an exceedingly short lifetime due to tidal disruption by the central black hole.

[114] Multiple X-ray sources have since been detected in the Andromeda Galaxy, using observations from the European Space Agency's (ESA) XMM-Newton orbiting observatory.

Robin Barnard et al. hypothesized that these are candidate black holes or neutron stars, which are heating the incoming gas to millions of kelvins and emitting X-rays.

M32 may once have been a larger galaxy that had its stellar disk removed by M31 and underwent a sharp increase of star formation in the core region, which lasted until the relatively recent past.

Andromeda is best seen during autumn nights in the Northern Hemisphere when it passes high overhead, reaching its highest point around midnight in October, and two hours earlier each successive month.

[146] An amateur telescope can reveal Andromeda's disk, some of its brightest globular clusters, dark dust lanes, and the large star cloud NGC 206.