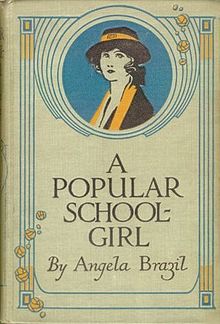

Angela Brazil

[citation needed] Though interest in girls' school stories waned after World War II, her books remained popular until the 1960s.

They were seen as disruptive and a negative influence on moral standards by some figures in authority during the height of their popularity, and in some cases were banned, or indeed burned, by headmistresses in British girls' schools.

[7] While her stories have been much imitated in more recent decades, and many of her motifs and plot elements have since become clichés or the subject of parody, they were innovative when they first appeared.

She presented a young female point of view which was active, aware of current issues and independent-minded; she recognised adolescence as a time of transition, and accepted girls as having common interests and concerns which could be shared and acted upon.

[3][8]: 166 [9] She was the youngest child of Clarence Brazil, a mill manager, and Angelica McKinnel, the daughter of the owner of a shipping line in Rio de Janeiro, who had a Spanish mother.

[1]: 51 She was primarily influenced by her mother, Angelica, who had suffered during her Victorian English schooling, and was determined to bring up her children in a liberated, creative and nurturing manner, encouraging them to be interested in literature, music and botany, a departure from the typical distant attitude towards children adopted by parents in the Victorian era.

Having been brought up to express herself freely, she shocked the younger Miss Knowles by removing the teacher's hair pins while sitting on her knee, an action little in keeping with the strict disciplinarian ethos of the school.

[10] Brazil first starting writing at age 10, producing a magazine with her close childhood friend Leila Langdale, which was modelled on Little Folks, a children's publication of the time she was very fond of.

[8]: 167 She was well known in Coventry high society as a hostess and threw parties for adults, with a greater number of female guests, at which children's food and games were featured.

She was quite late in taking up writing, developing a strong interest in Welsh mythology, and at first wrote a few magazine articles on mythology and nature - due most likely to spending holidays in an ancient cottage called Ffynnon Bedr in Llanbedr y Cennin, North Wales (a plaque at the cottage states she lived there 1902-1927).

[8]: 167 The story was autobiographical, with Brazil represented as the principal character Peggy, and her friend Leila Langdale appearing as Lilian.

In total she published 49 novels about life in boarding schools, and approximately 70 short stories, which appeared in magazines.

She wrote for girls gaining a greater level of freedom in the early 20th century and intended to capture their point of view.

[8]: 168 Her schools usually have between 20 and 50 pupils and so are able to create a community which is an extended family, but also of sufficient size to function as a kind of micro state, with its own traditions and rules.

[8]: 171 The schools tend to be situated in picturesque circumstances, being manors, having moats, being built on clifftops or on moors, and the style of teaching is often progressive, including experiments in self-expression, novel forms of exercise, and different social groups and activities for the girls.

They are adolescents, shown as being in a normal period of transition in their lives, with a restlessness that tends to be expressed by minor adventures such as climbing out of dormitory windows at night, playing pranks on one another and their teachers and searching for spies in their midst.

[8]: 171–172 The stories tend to focus on relationships between the pupils, including alliances between pairs and groups of girls, jealousy between them, and the experience of characters who feel excluded from the school community.

[8]: 180 In addition to her books, she also contributed a large number of school stories to children's annuals and the Girl's Own Paper.

A character in Brazil's The Third Class at Miss Kaye's quotes these novels as an example of the sort of rigid Victorian environment she had been expecting to find at boarding school.

Previously it had been common for girls to be educated by a private tutor, an approach which led to young women growing up with a feeling of isolation from their peers.

[8]: 175 Much of the fiction for girls being published at the turn of the century was instructional, and focused on promoting self-sacrifice, moral virtues, dignity and aspiring to a settled position in an ordered society.

Brazil's fiction presented energetic characters who openly challenged authority, were cheeky, perpetrated pranks, and lived in a world which celebrated their youth and in which adults and their concerns were sidelined.

[8]: 169 While popular with girls, Brazil's books were not approved of by many adults and even banned by some headmistresses, seeing them as subversive and damaging to young minds.

Her stories written before 1914, the beginning of the First World War, lean more towards issues of character that were typical in Victorian fiction for girls.

However, this may accord an undue influence to this literature, as there had been a gradual development from the 18th century toward fiction which was more specifically focused on gender,[8]: 175–176 and many of the tropes in Brazil's books derive from the real-life schools attended by early 20th-century girls.

J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series draws upon many elements of English public school education fiction that Brazil's work helped to establish.

It is possible that Brazil, writing about her own youthful experiences of schoolgirl life, was completely unaware of these implications, and passionate friendships between adolescent girls are not uncommon.

Over two decades she made detailed notes about plants, birds and animals she had seen as well as some watercolour paintings for her personal records.