Anglerfish

[citation needed] The earliest fossils of anglerfish are from the Eocene Monte Bolca formation of Italy, and these already show significant diversification into the modern families that make up the order.

[6][7] A 2010 mitochondrial genome phylogenetic study suggested the anglerfishes diversified in a short period of the early to mid-Cretaceous, between 130 and 100 million years ago.

[7] Other studies indicate that anglerfish only originated shortly after the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event as part of a massive adaptive radiation of percomorphs, although this clashes with the extensive diversity already known from the group by the Eocene.

[4][13] The relationships of the suborders within Lophiiformes as set out in Pietsch and Grobecker's 1987 Frogfishes of the world: systematics, zoogeography, and behavioral ecology is shown below.

[8] Lophioidei Antennarioidei Chaunacoidei Ogcocephaloidei Ceratioidei It has been found in phylogenetic studies that both the Lophiiformes and the Tetraodontiformes nest within the Acanthuriformes and are so classified as clades within that taxon.

[16] Frogfish and other shallow-water anglerfish species are ambush predators, and often appear camouflaged as rocks, sponges or seaweed.

[17] Anglerfish have a flap, or the illicium, towards the distal end of their body on their first of two dorsal fins which extends to the snout and acts as a luring mechanism where prey will approach in a face-to-face manner.

[19] Specifically considering Cryptopsaras couesii, this deep sea ceratioid anglerfish has unique rotational biomechanics in its musculature.

The robust retractor and protractor muscles move in a winding pattern in opposite directions along the length of the pterygiophore, which exists in a deep longitudinal ridge along the skull.

[19] Further, the long and thin inclinator of the deep sea ceratioid anglerfish allows for a distinctly wide range of anterior and posterior motion, assisting in the movement of the luring apparatus to aid in the ambush of prey.

[19] Most adult female ceratioid anglerfish have a luminescent organ called the esca at the tip of a modified dorsal ray (the illicium or fishing rod; derived from Latin ēsca, "bait").

The source of luminescence is symbiotic bacteria that dwell in and around the esca, enclosed in a cup-shaped reflector containing crystals, probably consisting of guanine.

[21] The bacterial symbionts are not found at consistent levels throughout stages of anglerfish development or throughout the different depths of the ocean.

A pore connects the esca with the seawater, which enables the removal of dead bacteria and cellular waste, and allows the pH and tonicity of the culture medium to remain constant.

[3] In a study on Ceratioid anglerfish in the Gulf of Mexico, researchers noticed that the confirmed host-associated bioluminescent microbes are not present in the larval specimens and throughout host development.

[2] Photobacterium phosphoreum and members from kishitanii clade constitute the major or sole bioluminescent symbiont of several families of deep-sea luminous fishes.

[25] In most species, a wide mouth extends all around the anterior circumference of the head, and bands of inwardly inclined teeth line both jaws.

[26] The anglerfish is able to distend both its jaw and its stomach, since its bones are thin and flexible, to enormous size, allowing it to swallow prey up to twice as large as its entire body.

[27] In 2005, near Monterey, California, at 1,474 metres depth, an ROV filmed a female ceratioid anglerfish of the genus Oneirodes for 24 minutes.

This first spine protrudes above the fish's eyes and terminates in an irregular growth of flesh (the esca), and can move in all directions.

In some species of anglerfish, fusion between male and female when reproducing is possible due to the lack of immune system keys that allow antibodies to mature and create receptors for T-cells.

Males of some species also develop large, highly specialized eyes that may aid in identifying mates in dark environments.

The male ceratioids are significantly smaller than a female anglerfish, and may have trouble finding food in the deep sea.

[4] One explanation for the evolution of sexual symbiosis is that the relatively low density of females in deep-sea environments leaves little opportunity for mate choice among anglerfish.

Males would be expected to shrink to reduce metabolic costs in resource-poor environments and would develop highly specialized female-finding abilities.

Higher densities of male-female encounters might correlate with species that demonstrate facultative symbiosis or simply use a more traditional temporary contact mating.

[38] The spawn of the anglerfish of the genus Lophius consists of a thin sheet of transparent gelatinous material 25 cm (10 in) wide and greater than 10 m (33 ft) long.

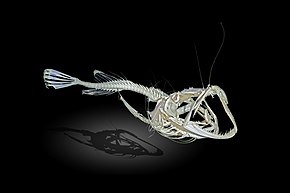

(B) Cryptopsaras couesii , 34.5 mm SL

(C) Himantolophus appelii , 124 mm SL

(D) Diceratias trilobus , 86 mm SL

(E) Bufoceratias wedli , 96 mm SL

(F) Bufoceratias shaoi , 101 mm SL

(G) Melanocetus eustalus , 93 mm SL

(H) Lasiognathus amphirhamphus , 157 mm SL

(I) Thaumatichthys binghami , 83 mm SL

(J) Chaenophryne quasiramifera , 157 mm SL.