Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement

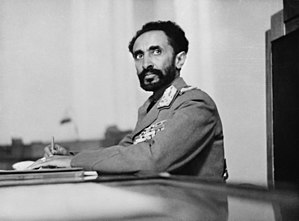

[1] Britain sent civil advisers to assist Selassie with administrative duties and also provide him with military advisors to maintain internal security and to improve and modernize the Ethiopian army.

Haile Selassie described one aspect of the prior relationship, "they took all the military equipment captured in Our country... openly and boldly saying that it should not be left for the service of blacks.

There were two revolts during this time: the Woyane rebellion in eastern Tigray Province, which was suppressed with the assistance of British air support; and the other in the Ogaden which was put down by two battalions of Ethiopian forces.

"[13] In the end, Ethiopian officials overcame their trepidation and had the three-month notice of termination delivered to the British chargé d'affaires 25 May 1944 along with a request for the prompt negotiations of a new agreement.

Only after the Ethiopian government reminded them of the expiry of the agreement 16 August and that they were looking forward to receiving possession of the railway and administration of the Haud and Reserved Area, did the British respond.

Initially the British attempted to delay the termination of the agreement, claiming it could not accommodate the Ethiopian demands, and settled for a two-month extension for the date to hand the properties over.

A negotiating team led by the Earl de la Warr arrived 26 September, and over the following months both sides argued until 19 December 1944, when a new Anglo-Ethiopian agreement was signed and Britain agreed to relinquish several advantages they had enjoyed in Ethiopia.

[15] Specifically Britain would remove her garrisons, except from the Ogaden; open Ethiopia's airfields (heretofore restricted to British traffic) to all Allied aircraft; and give up direct control of the Ethiopian section of the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railroad.